1 Introduction

2 Extension of the Concept of Local Heat Distribution to Molecular Devices

Fig. 1 (Color online) The molecular nanoelectronic device (E-M$_{1}$-E) studied in this work (a), and parallel (b), perpendicular (c), and diagonal (d) intra-molecular partitioning schemes adopted for the analysis of the thermoelectric performance of this system. The Au atoms represent the electrodes. |

Fig. 2 (Color online) Local differential electron density map, $\Delta \rho (S_{i}, \varepsilon )=\sum\limits_{\Omega \in S_{i} }^{N_{S_{i} } } {\rho (\Omega ;\varepsilon )} -{\kern 1pt}\sum\limits_{\Omega \in S_{i} }^{N_{S_{i} } } {\rho (\Omega ;0)} $, obtained for the E-M$_{1}$-E system at EF of $\varepsilon =60\times 10^{-4}~{\rm au}$ strength, determining the donor ($n$-type-like) and acceptor ($p$-type-like) intra-molecular sections, highlighted in red and blue, respectively. |

3 Phenomenological Analysis of the Intra-Molecular Thermoelectric-Like Effects

Fig. 3 (Color online) Pictorial presentation of the local kinetic energy transfer between different diagonal pairs of IMTLSs, Eq. (12). The intra-molecular/sectional kinetic energy transfer, $\Delta K_{\gamma } (S_{i},\varepsilon )$, and differential kinetic energy between the diagonal pair of sections,$\nabla_{xy, \varepsilon } K_{\gamma }$, and kinetic energy (heat-like) flux between the corresponding pair of IMTLSs, $\Delta_{\gamma } (\varepsilon )/dt_{\gamma } $, in the EF of $\varepsilon $strength, are also shown. |

4 Modeling Intra-Molecular Energy Dissipation/Transfer in Field-Effect Nanoelectronic Molecular Devices

5 Local Intra-Molecular Electronic Energy Dissipation

6 Computational Details

7 Results and Discussion

Fig. 4 (Color online) Intra-molecular atomic electronic (a) and vibrational (b) temperature changes calculated for some representative atoms of the E-M$_{1}$-E system at $\varepsilon =30\times 10^{-4}~{\rm au}$. |

Fig. 5 (Color online) (a) Intra-molecular atomic electronic and vibrational temperature changes of the end gold-sulfur (-Au-S-) junctions (contact points) of the E-M$_{1}$-E system, as functions of the EF strength. (b) The current-voltage $(I$-$V)$ characteristic curve predicted for the E-M$_{1}$-E device. |

Fig. 6 (Color online) (a) The total intra-molecular Joule-like, Peltier-like and Thomson-like heat fluxes, ${\rm { J}}_{\rm tot} (S_{\rm DL}, S_{\rm DR} )={\rm { J}}_{{\rm elec}} (S_{\rm DL}, S_{\rm DR} )+{\rm { J}}_{\rm vib} (S_{\rm DL}, S_{\rm DR} )$, calculated at different EF strengths, for diagonal IMTLSs calculated for the E-M$_{1}$-E device. The electronic (b), $Q_{{\rm elec}}^{\rm TL} (S_{i},S_{j} )$, and vibrational (c), $Q_{\rm vib}^{\rm TL} (S_{i}, S_{j} )$, intra-molecular Thomson-like heatings of the parallel, L-R$(S_{\rm L},S_{\rm R} )$, perpendicular, U-D$(S_{\rm U},S_{\rm D} )$, and diagonal, DL-DR$(S_{\rm DL},S_{\rm DR} )$, IMTLSs of the E-M$_{1}$-E device (Fig. 1). All values are normalized to the corresponding largest values set at 100. |

Fig. 7 (Color online) The E-M$_{2}$-E molecular device studied in this work (a), and its electronic (b) and vibrational (c) intra-molecular Peltier-like coefficients (IMPLC) calculated at different electric field strengths. |

Fig. 8 (Color online) (a) Size of the electric dipole moment vector and its components (in Debye) at various EF strengths, and (b) electric field effects on the energies of the occupied (O) and virtual (V) molecular orbitals, calculated for the E-M$_{2}$-E molecular device at DFT-B3LYP/6-31G* level of theory using LANL2DZ basis set and pseudopotential for gold atoms. |

Fig. 9 (Color online) The relative differential intra-molecular thermoelectric-like figure of merit, $\% \Delta {\kern 1pt}ZT_{q,{\rm eff}}^{M} (S_{i},S_{j} )$, defined in Eq. (26), of the parallel, perpendicular, and diagonal IMTLSs of the E-M$_{1}$-E and E-M$_{2}$-E molecular devices, introduced in Figs. 1(a) and 7(a), respectively. |

Table 1 The most (least) energy-dissipative section MEDS (LES), $\eta_{\max }^{\rm dis} (S_{i},\varepsilon )(\eta_{\min }^{\rm dis} (S_{i}, \varepsilon ))$ of the proposed molecular nanoelectronic device E-M$_{1}$-E (Fig. 1) induced by external electric field (EF) with various strengths $(\varepsilon)$ applied in the $\pm x$ directions. |

|

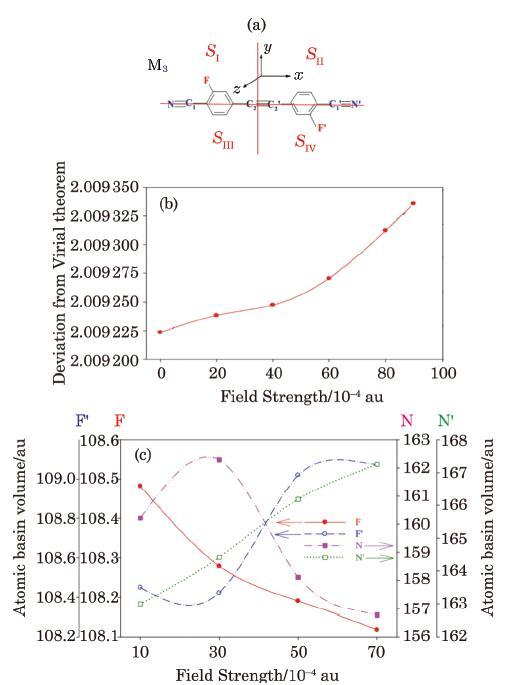

Fig. 10 (Color online) (a) The isolated molecular system M$_{3}$ studied in this work. (b) Examination of the validity of the virial theorem for the M$_{3}$ molecule at different EF strengths. (c) The QTAIM atomic basin volumes as an index of the response of the molecular system M$_{3}$. To external electric field. |

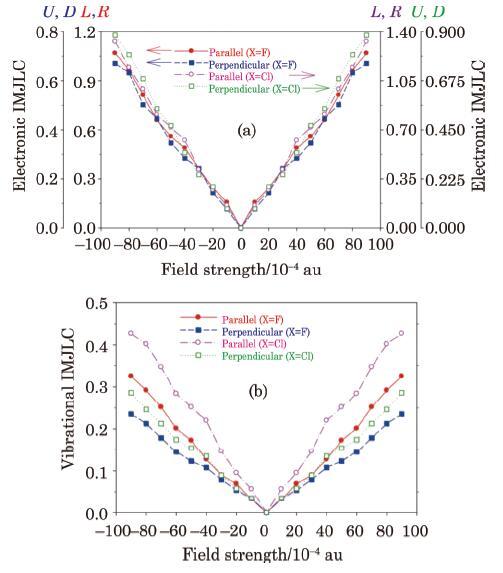

Fig. 11 (Color online) The electric field effect on the electronic (a) and vibrational (b) intra-molecular Joule-like coefficients (IMJLC) calculated for the molecular system M$_{3}$ (introduced in Fig. 11) with two fluorine (X$=$F) and chlorine (X$=$Cl) substitutions. |