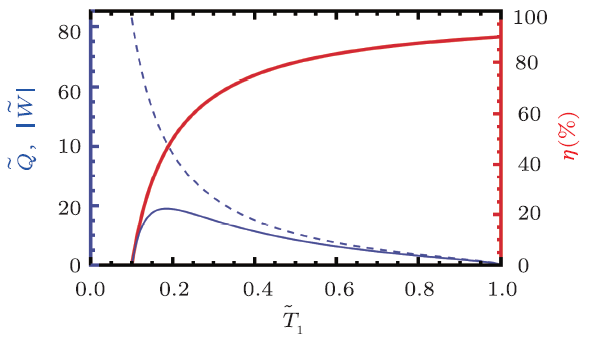

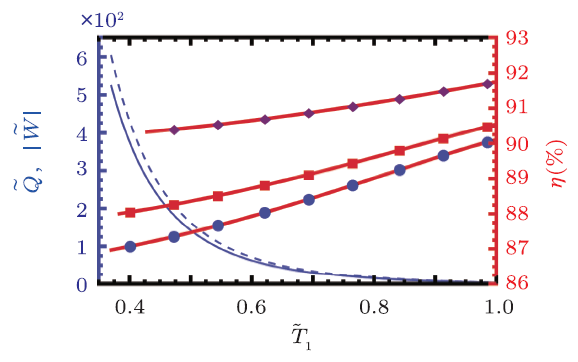

The reduced heat, work, and efficiency are shown in

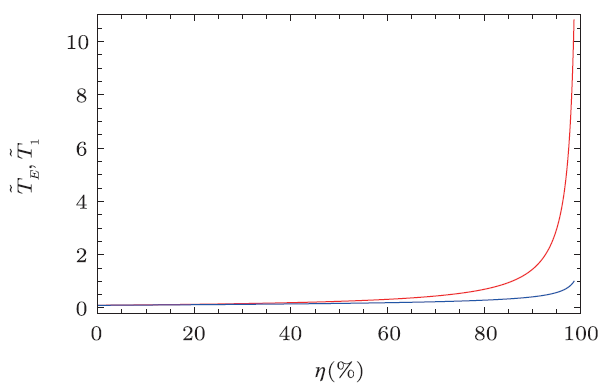

Fig. 5. The low temperature is also set to $\tilde{T}_{2}=0.1$. From the figure, one can clearly see that the behavior of this BPR cycle is very different from the Rankine cycle without the back pressure mechanism. Both more work and higher efficiency can be achieved at the same time. Thus, the left thing is to rise the reduced temperature $\tilde{T}_{1}$ for a high efficiency. However, we should keep in mind that $\tilde{T}_{1}$ is not the highest temperature for the engine to operate, while $\tilde{T}_{E}$ is. Since the normal working of the heat engine is limited with the temperature, $\tilde{T}_{E}$ should be not too high. We clearly show the temperatures $\tilde{T}_{E}$ and $\tilde{T}_{1}$ as functions of the efficiency in

Fig. 6. For low efficiency, $\tilde{T}_{E}$ almost meets $\tilde{T}_{1}$. However, when the efficiency increases up to 60 %, the difference between them will be obvious. When exceed that value, the temperature $\tilde{T}_{E}$ has a rapidly increase than $\tilde{T}_{1}$. More precisely, we list some numerical data in

Table 2, which shows that in order to achieve the efficiency $\eta$, how high the temperatures $\tilde{T}_{1}$ and $\tilde{T}_{E}$ should be. For small $\eta$, the highest temperature $\tilde{T}_{E}$ of the heat engine is small. However if one wonders an efficiency larger than 90 %, $\tilde{T}_{E}$ will rapidly increase. For example, $\eta=96$ % requires $\tilde{T}_{E}=3.70$, and $\eta=98 %$ requires $\tilde{T}_{E}=7.45$. Nevertheless, the BPR cycle still has a higher efficiency than the standard Rankine cycle.