The heterogeneous mean-field (HMF) theory has been widely used to study dynamical processes on complex networks.

[3,5-6] This theory is based on the assumption that the nodes of the same degree are statistically equivalent. The main purpose of the HMF theory is to derive the dynamical equations for the quantities of interest in different degree classes. In general, the set of dynamical equations are intertwined with each other. However, for degree uncorrelated networks, they can be reduced to a single equation for an order parameter, such as the average magnetization in the Ising model

[8] and the average infection probability in the susceptible-infected-susceptible model.

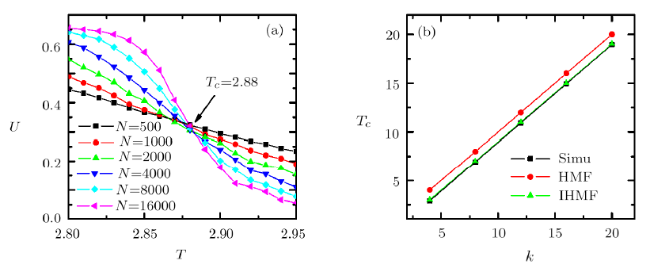

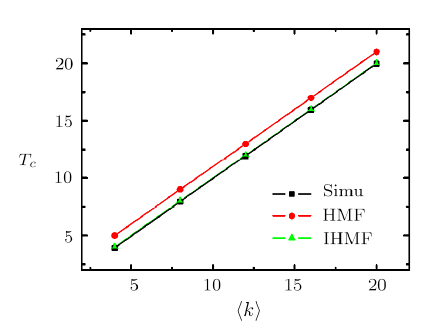

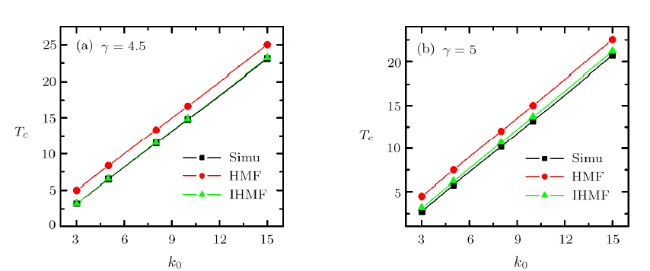

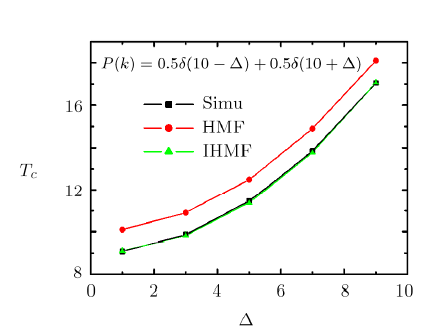

[14] By linear stability analysis near the phase transition point, the HMF theory can produce an elegant analytical result of the phase transition point. For example, it has been shown that the critical temperature of the Ising model is $T_c=\langle {k^2} \rangle / \langle {k} \rangle $,

[8] where $\langle {k^n} \rangle$ is the $n$th moment of degree distribution $P(k)$. For scale-free networks, $P(k) \sim k ^{-\gamma}$ with the exponent $\gamma<3$, $\langle {k^2} \rangle$ is divergent, and thus $T_c \rightarrow \infty$. The HMF theory has also shown its power in many other models, such as rumor spreading model,

[31-32] metapopulation model,

[33] zero-temperature Ising model,

[34-35] majority-vote model,

[36-37] etc.