1. Introduction

2. Theoretical method

3. Results and discussions

Table 1. The SLy5, T22, T32 and T43 parameter sets. |

| Parameters | SLy5 [91] | T22 [61] | T32 [61] | T43 [61] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t0 (MeV fm3) | −2484.88 | −2484.40 | −2486.16 | −2490.28 | |

| t1 (MeV fm5) | 483.13 | 484.50 | 489.07 | 494.61 | |

| t2 (MeV fm5) | −549.40 | −471.45 | −438.57 | −255.53 | |

| t3 (MeV fm4) | 13 673.00 | 13 786.97 | 13 804.97 | 13 847.12 | |

| x0 | 0.778 | 0.730 | 0.712 | 0.699 | |

| x1 | −0.328 | −0.443 | −0.499 | −0.782 | |

| x2 | −1.000 | −0.945 | −0.912 | −0.646 | |

| x3 | 1.267 | 1.188 | 1.160 | 1.136 | |

| W0 (MeV fm3) | 126.00 | 123.23 | 133.59 | 153.10 | |

| σ | 1/6 | 1/6 | 1/6 | 1/6 | |

| t${}_{{\rm{e}}}$ (MeV fm5) | — | 118.69 | 204.35 | 196.87 | |

| t${}_{{\rm{o}}}$ (MeV fm5) | — | −72.50 | −77.18 | −49.16 |

Table 2. The S2n values of the Z = 114 isotopes with the SLy5, T22, T32 and T43 interactions and the WS4 mass table. The S2n values are measured in MeV. |

| Nuclei | S2n (SLy5) | S2n (T22) | S2n (T32) | S2n (T43) | S2n (WS4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 274114 | 16.27 | 16.38 | 16.30 | 16.34 | 17.03 | |

| 276114 | 15.80 | 15.92 | 15.84 | 15.79 | 16.67 | |

| 278114 | 15.04 | 15.16 | 15.11 | 15.03 | 15.67 | |

| 280114 | 14.32 | 14.43 | 14.40 | 14.29 | 15.10 | |

| 282114 | 13.69 | 13.77 | 13.78 | 13.66 | 14.81 | |

| 284114 | 13.60 | 13.60 | 13.69 | 13.65 | 14.52 | |

| 286114 | 13.09 | 13.19 | 13.19 | 13.07 | 13.86 | |

| 288114 | 12.43 | 12.69 | 12.67 | 12.84 | 13.40 | |

| 290114 | 12.68 | 12.87 | 12.79 | 12.74 | 12.79 | |

| 292114 | 12.07 | 12.19 | 12.19 | 12.07 | 12.47 | |

| 294114 | 11.60 | 11.90 | 11.77 | 11.78 | 11.71 | |

| 296114 | 11.34 | 11.45 | 11.59 | 11.34 | 11.25 | |

| 298114 | 10.91 | 11.18 | 11.24 | 11.26 | 10.64 | |

| 300114 | 7.45 | 7.54 | 7.68 | 7.68 | 8.53 | |

| 302114 | 7.28 | 7.34 | 7.48 | 7.48 | 8.25 | |

| 304114 | 8.46 | 8.35 | 8.47 | 8.36 | 8.72 | |

| 306114 | 9.06 | 8.98 | 8.81 | 8.58 | 8.88 | |

| 308114 | 8.64 | 8.78 | 8.80 | 8.74 | 8.88 | |

| 310114 | 8.32 | 8.40 | 8.43 | 8.35 | 9.01 | |

| 312114 | 7.90 | 8.04 | 8.07 | 7.95 | 8.50 | |

| 314114 | 7.57 | 7.66 | 7.69 | 7.61 | 8.21 | |

| 316114 | 7.25 | 7.36 | 7.40 | 7.27 | 7.58 | |

| 318114 | 6.92 | 7.04 | 7.08 | 7.00 | 7.06 | |

| 320114 | 6.61 | 6.74 | 6.76 | 6.67 | 6.98 | |

| 322114 | 6.37 | 6.49 | 6.51 | 6.47 | 6.89 | |

| 324114 | 6.06 | 6.55 | 6.53 | 6.51 | 6.78 | |

| 326114 | 5.97 | 6.23 | 6.25 | 6.16 | 6.38 | |

| 328114 | 5.77 | 5.95 | 5.95 | 5.87 | 6.05 | |

| 330114 | 5.44 | 5.57 | 5.61 | 5.53 | 5.84 | |

| 332114 | 5.21 | 5.30 | 5.35 | 5.30 | 5.35 | |

| 334114 | 4.91 | 5.07 | 5.07 | 4.99 | 5.13 |

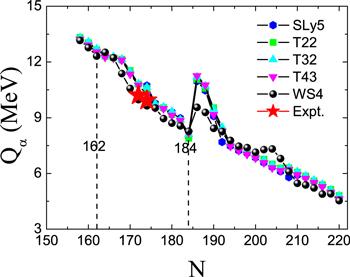

Figure 2. The Q${}_{\alpha }$ values of the Z = 114 isotopes versus N by the SLy5, T22, T32 and T43 interactions. The filled circles represent the Q${}_{\alpha }$ values extracted from the WS4 mass model [13, 14]. The experimental Q${}_{\alpha }$ values of ${}^{\mathrm{286,288}}114$ are taken from [3, 4] and marked with the red stars. |

Table 3. Same as table 1, but for the Q${}_{\alpha }$ values. The Q${}_{\alpha }$ values are measured in MeV. |

| Nuclei | Q${}_{\alpha }$ (SLy5) | Q${}_{\alpha }$ (T22) | Q${}_{\alpha }$ (T32) | Q${}_{\alpha }$ (T43) | Q${}_{\alpha }$ (WS4) | Q${}_{\alpha }$ (Expt.) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 272114 | 13.28 | 13.32 | 13.31 | 13.22 | 13.16 | ||

| 274114 | 13.03 | 13.04 | 13.08 | 12.90 | 12.78 | ||

| 276114 | 12.66 | 12.66 | 12.71 | 12.54 | 12.32 | ||

| 278114 | 12.33 | 12.31 | 12.36 | 12.26 | 12.52 | ||

| 280114 | 12.24 | 12.23 | 12.28 | 12.21 | 12.23 | ||

| 282114 | 12.10 | 12.15 | 12.15 | 12.10 | 11.38 | ||

| 284114 | 11.44 | 11.54 | 11.48 | 11.34 | 10.57 | ||

| 286114 | 10.79 | 10.81 | 10.83 | 10.74 | 9.97 | 10.21±0.04 [4] | |

| 288114 | 10.73 | 10.58 | 10.63 | 10.26 | 9.65 | 9.93±0.03 [4] | |

| 290114 | 9.78 | 9.63 | 9.75 | 9.55 | 9.52 | ||

| 292114 | 9.51 | 9.54 | 9.58 | 9.49 | 8.95 | ||

| 294114 | 9.31 | 9.17 | 9.34 | 9.12 | 8.71 | ||

| 296114 | 8.98 | 8.86 | 8.88 | 8.84 | 8.56 | ||

| 298114 | 7.99 | 7.89 | 8.11 | 8.18 | 8.27 | ||

| 300114 | 10.96 | 11.06 | 11.19 | 11.26 | 9.56 | ||

| 302114 | 10.46 | 10.58 | 10.71 | 10.76 | 9.29 | ||

| 304114 | 9.08 | 9.54 | 9.47 | 9.17 | 8.43 | ||

| 306114 | 7.69 | 8.27 | 8.49 | 8.28 | 8.26 | ||

| 308114 | 7.47 | 7.61 | 7.61 | 7.46 | 7.77 | ||

| 310114 | 7.23 | 7.42 | 7.39 | 7.24 | 7.47 | ||

| 312114 | 7.09 | 7.19 | 7.17 | 7.03 | 7.39 | ||

| 314114 | 6.85 | 6.95 | 6.94 | 6.83 | 7.14 | ||

| 316114 | 6.58 | 6.76 | 6.72 | 6.58 | 7.28 | ||

| 318114 | 6.33 | 6.50 | 6.47 | 6.30 | 7.32 | ||

| 320114 | 6.11 | 6.29 | 6.25 | 6.15 | 6.80 | ||

| 322114 | 5.79 | 6.30 | 6.30 | 6.20 | 6.10 | ||

| 324114 | 5.91 | 6.06 | 6.10 | 5.94 | 5.47 | ||

| 326114 | 5.80 | 5.86 | 5.87 | 5.73 | 5.38 | ||

| 328114 | 5.55 | 5.61 | 5.63 | 5.51 | 5.22 | ||

| 330114 | 5.34 | 5.40 | 5.40 | 5.29 | 4.89 | ||

| 332114 | 5.02 | 5.14 | 5.12 | 4.98 | 4.90 | ||

| 334114 | 4.67 | 4.81 | 4.80 | 4.64 | 4.54 |

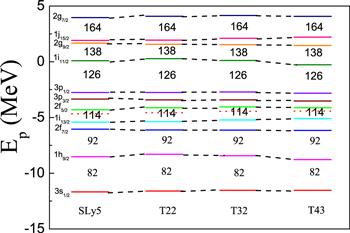

Figure 3. The single-proton energy spectra of 298114 near the Fermi levels by the SLy5, T22, T32 and T43 interactions. The red dot lines denote the Fermi levels. The same orbitals are linked with the black dashed lines. |

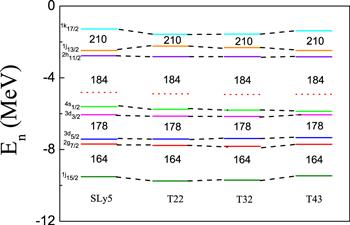

Figure 4. Same as figure 3, but for the single-neutron energy spectra. |

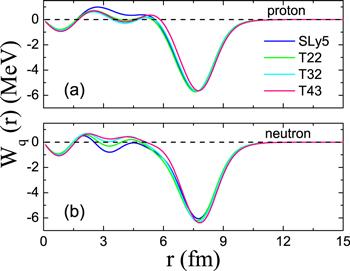

Figure 5. The proton and neutron spin–orbit potentials of 298114 by the SLy5, T22, T32 and T43 interactions. |

Table 4. The proton pseudospin orbital splittings and pseudospin doublets of the $1\widetilde{g}$ (2f ${}_{7/2}$-1h${}_{9/2}$), $2\widetilde{d}$ (3p${}_{3/2}$-2f ${}_{5/2}$), and $1\widetilde{h}$ (2g${}_{9/2}$-1i${}_{11/2}$) of 298114 by the SLy5, T22, T32 and T43 interactions. |

| Skyrme interactions | ${\rm{\Delta }}\varepsilon $(MeV) | $\overline{s}$(MeV) | c | Symmetry | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| | |||||

| $1\widetilde{g}$ (2f ${}_{7/2}$−1h${}_{9/2}$) | |||||

| | |||||

| SLy5 | 2.462 | 1.549 | 1.589 | N | |

| T22 | 2.174 | 1.459 | 1.490 | N | |

| T32 | 2.303 | 1.610 | 1.430 | N | |

| T43 | 2.623 | 1.839 | 1.426 | N | |

| | |||||

| $2\widetilde{d}$ (3p${}_{3/2}$−2f ${}_{5/2}$) | |||||

| | |||||

| SLy5 | 0.961 | 0.776 | 1.238 | N | |

| T22 | 0.716 | 0.685 | 1.045 | N | |

| T32 | 0.635 | 0.668 | 0.951 | Y | |

| T43 | 0.604 | 0.654 | 0.924 | Y | |

| | |||||

| $1\widetilde{h}$ (2g${}_{9/2}$−1i${}_{11/2}$) | |||||

| | |||||

| SLy5 | 1.587 | 0.912 | 1.740 | N | |

| T22 | 1.286 | 0.828 | 1.553 | N | |

| T32 | 1.424 | 0.997 | 1.428 | N | |

| T43 | 1.726 | 1.238 | 1.394 | N | |

Table 5. Same as table 3, but for the pseudospin neutron doublets $2\widetilde{f}$ (2g${}_{7/2}$−3d${}_{5/2}$), $3\widetilde{p}$ (3d${}_{3/2}$−4s${}_{1/2}$), and $1\widetilde{i}$ (2h${}_{11/2}$−1j${}_{13/2}$). |

| Skyrme interactions | ${\rm{\Delta }}\varepsilon $ (MeV) | $\overline{s}$(MeV) | c | Symmetry | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| | |||||

| 2 $\widetilde{f}$ (2g${}_{7/2}$-3d${}_{5/2}$) | |||||

| | |||||

| SLy5 | 0.271 | 0.695 | 0.390 | Y | |

| T22 | 0.360 | 0.673 | 0.545 | Y | |

| T32 | 0.433 | 0.673 | 0.643 | Y | |

| T43 | 0.374 | 0.614 | 0.609 | Y | |

| | |||||

| 3 $\widetilde{p}$ (3d${}_{3/2}$-4s${}_{1/2}$) | |||||

| | |||||

| SLy5 | 0.451 | 0.695 | 0.649 | Y | |

| T22 | 0.383 | 0.673 | 0.569 | Y | |

| T32 | 0.360 | 0.673 | 0.535 | Y | |

| T43 | 0.198 | 0.614 | 0.322 | Y | |

| | |||||

| 1 $\widetilde{i}$ (2h${}_{11/2}$-1j${}_{13/2}$) | |||||

| | |||||

| SLy5 | 0.289 | 0.746 | 0.387 | Y | |

| T22 | 0.593 | 0.627 | 0.946 | Y | |

| T32 | 0.507 | 0.627 | 0.809 | Y | |

| T43 | 0.351 | 0.724 | 0.485 | Y | |

4. Conclusions

| i | (i) The predicted accuracy is improved slightly by the tensor force although the tensor force contribution to the S2n values is small. |

| ii | (ii) The experimental Q${}_{\alpha }$ values are reproduced better with the WS4 model by comparing with the results with the SHFB approach. |

| iii | (iii) For each interaction, the shell closure at N = 184 can be seen evidently by analyzing the S2n and Q${}_{\alpha }$ evolutions with N and the single-neutron energy spectra. |

| iv | (iv) The single-nucleon energy spectra are almost not influenced by the tensor force and it is not easy to observe the tensor force effect in the nuclear ground state of Z = 114 isotopes. |

| v | (v) The pseudospin symmetry is dependent on the type of the Skyrme interactions with the tensor force. Moreover, the neutron pseudospin symmetries are preserved better than the proton ones. |