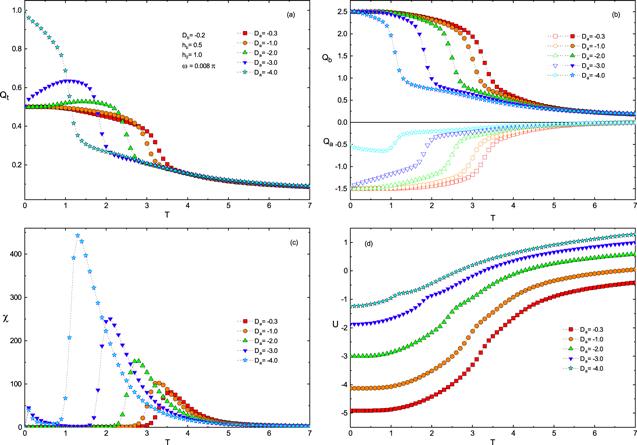

Figure

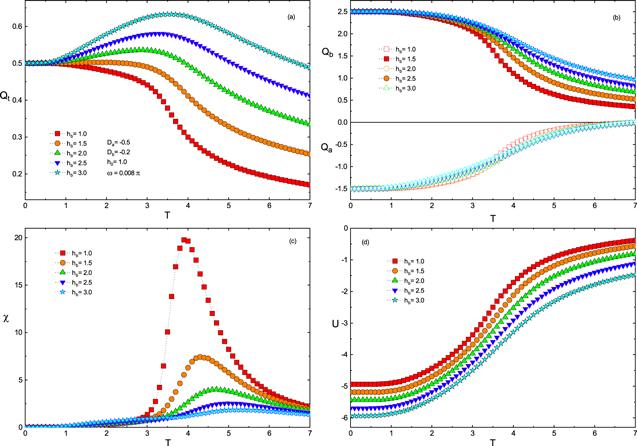

3 exhibits temperature dependence of the dynamic order parameter of the system

${Q}_{t}$ , the dynamic order parameters of the sublattices

Q a ,

Q b , susceptibility

χ, and internal energy

U for different values of

D a with

D b = −0.2,

h b = 0.5,

h 0 = 1.0,

ω = 0.008

π . In figure

3 (a), one can observe two saturation values (

Q t = 0.5, 1.0) at zero temperature corresponding to two configurations of sublattice spin states (−3/2, 5/2) and (−1/2, 5/2) at the ground state, which can be calculated as:

${Q}_{t}=\tfrac{{20}^{2}\times (-1.5)+{20}^{2}\times 2.5}{2\,\times \,{20}^{2}}=0.5$ and

${Q}_{t}=\tfrac{{20}^{2}\times (-0.5)+{20}^{2}\times 2.5}{2\,\times \,{20}^{2}}=1.0$ , respectively.

Q t curves with different values of

D a can display abundant changing profiles. It is clearly seen that the curves labeled

D a = −0.3, −1.0, −4.0 keep a downward trend all through as

T increases until they are almost constant at high temperature region. However, a bulge which rises a little and then falls can be observed in the curves labeled

D a = −2.0, −3.0, which can be explained that frustrated spin states created by thermal agitation are released and different coexisting spin states are produced. As

T increases, all of the

Q t curves change from their saturation values and finally converge to a non-zero constant value at high temperature region.This non-zero constant value results from the existence of

h b . In addition, when

T > 3.5,

Q t is the same at the same

T no matter how large

D a is. This is because higher

T can promote the spin value to zero and thus reduce

Q t . In the high temperature region, the influence of temperature rather than

D a on

Q t is dominant. Similar behaviors also have been found in the mixed-spin (1/2, 3/2) Ising ferrimagnetic system [

40]. One can notice from figure

3 (b) that there exist two saturation values

${Q}_{a}=-0.5\left({D}_{a}=-4.0\right)$ and

${Q}_{a}=-1.5\left({D}_{a}=-0.3,-1.0,-2.0,-3.0\right)$ in

Q a curves and only one saturation value

Q b = 2.5 in

Q b curves, which should be responsible for the formation of saturation values in figure

3 (a). It follows that strong crystal field (

D a = −4.0) forces the sublattice. A from high-spin state to low-spin state and then leads to the presence of various saturation values of

Q a . Figure

3 (c) shows the temperature dependence of

χ curves for certain parameters. One can notice that there exist one or two peaks in each

χ curve, it is worth noting that the peak at higher temperature corresponds to the critical temperature

T C . Obviously,

T C decreases monotonously with the increase of

$\left|{D}_{a}\right|$ . Similar behavior has been observed in other theoretical studies of nano-structures [

57 –

60]. It is interesting that the peaks of the double-peak susceptibility curves at lower temperatures correspond to dramatic changes in the magnetization curve. It is remarkably that this double-peak phenomenon of susceptibility curves has been found by both MC simulation [

61 –

64] and EFT [

18,

65]. It can be observed from figure

3 (d) that

U increases with the increase of

T . In addition, it also increases as

$\left|{D}_{a}\right|$ increases, in other words, the strong crystal field makes the system unstable. Moreover, a flection point can be found in each

U curve at

T C, which reflects that the process of phase transition is accompanied by the fluctuation of system energy.