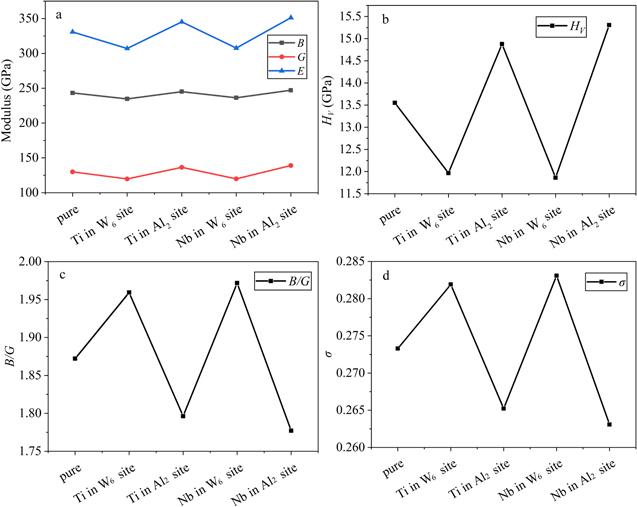

The bulk modulus

B and shear modulus

G reflect the ability to withstand the volume change under pressure and shear deformation under shear pressure, respectively [

42]. In figure

3(a), the values of

B and

G decline (increase), with the occupation of Ti and Nb in the W

6 (Al

2) site, which means that the resistance ability to volume change and shape change by applied pressure is reduced (improved). Young’s modulus

E can be used as a qualitative indicator to reflect the hardness of a material, and a large value of

E indicates that the solid is hard [

43]. It shows that with adding Ti and Nb in the W

6 site, the values of

E decline, which clarifies that the hardness of the doped system decreases. This is consistent with the content in figure

3(b), which is that the

HV value reduces with the addition of Ti and Nb in the W

6 site. However, the change of

E and

HV value in the system of the Al

2 site occupied by Ti and Nb is the opposite. The hardness of a metal is generally expressed by its resistance to local deformation [

44]. It is obvious that Ti and Nb occupying the W

6 site weaken the ability of the alloy to resist deformation, compared to the Al

2 site. The ratios between bulk modulus and shear modulus

B/

G and Poisson’s ratio

σ reflect the brittleness and ductility of a material [

42]. A high (low)

B/

G value signifies a tendency for ductility (brittleness), and 1.75 is a key value to assess ductility and brittleness [

42]. In figure

3(c), all the

B/

G values are larger than 1.75, which indicates that both the pure system and doped system are ductile. Poisson’s ratio

σ (−1 <

σ < 0.5) can represent the shear resistance of a material [

45]. A high Poisson’s ratio

σ means that the material has good plasticity [

45]. Figure

3(d) shows that Ti and Nb occupying the W

6 (Al

2) site are able to enhance (decrease) the plasticity of the alloy, probably since the system doped in the W

6 site is more metallic than that in the Al

2 site, which is stated in the section on electronic structures. The ductility is closely related to the fracture mechanisms and embrittlement, and generally, achieving high

σ is regarded as an approach to improve the toughness [

46-

48]. It is obvious that Ti and Nb occupying the W

6 site result in less likelihood of fracture and embrittlement, which provides the direction of the design of the Co-based alloy.