1. Introduction

2. Fluctuations and coexistence phenomena in two dimensions

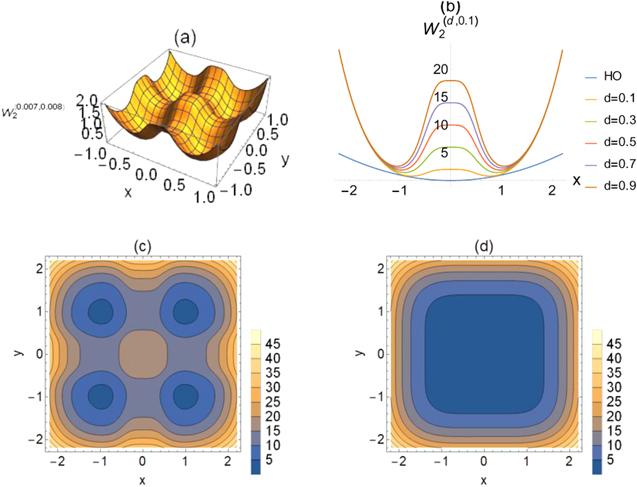

Figure 1. (a) The three-dimensional representation of the DLPs ${W}_{2}^{(0.007,0.008)}\left(x,y\right).$ (b) The vertical cross-sections of the DLPs ${W}_{2}^{(d,0.1)}\left(x,y\right).$ (c) and (d) are the two-dimensional representation of the potentials ${W}_{2}^{(1,0.1)}\left(x,y\right)$ and ${W}_{2}^{(1,1)}\left(x,y\right),$ respectively (contour plots). The potential changes from four minima potential to approximately flat minimum potential, ${H}_{2}.$ (For interpretation of the colors in the figure(s), the reader is referred to the web version of this article.) |

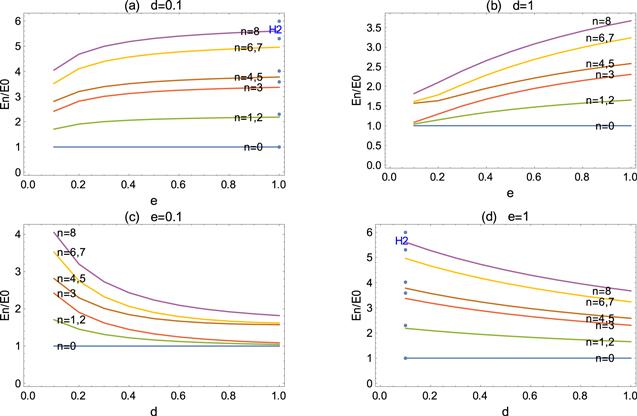

Figure 2. Representation of the first nine energy levels, as a function of $d$ and $e$ for DLPs ${W}_{2}^{(d,e)}\left(x,y\right),$ (normalized to the ground state energy). (a) and (b) show the behavior of the spectra of the DLPs ${W}_{2}^{(d,e)}\left(x,y\right)$ against the parameter $e$ with $d=0.1$ and $1,$ respectively. However, (c) and (d) display the energy spectra of the potential against the parameter $d$ with $e=0.1$ and $1,$ respectively. |

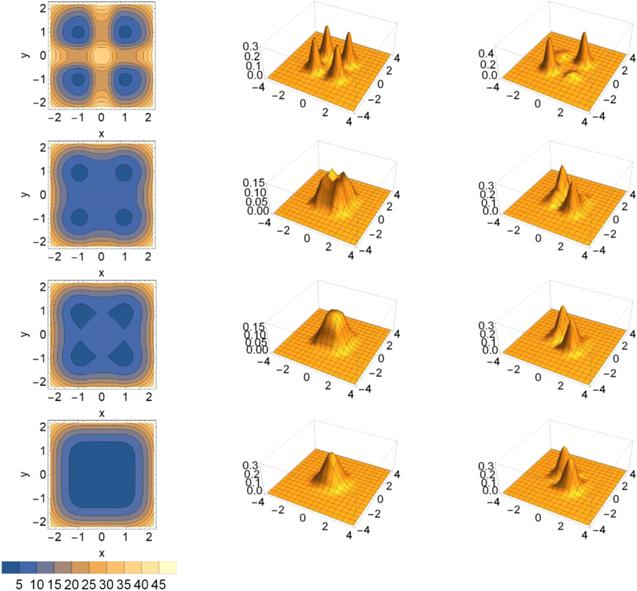

Figure 3. The contour plots of the DLPs ${W}_{2}^{(1,e)}\left(x,y\right)$ (left panel), the ground state probability density (medial panel), and the probability density of first excited state (right panel), as $e=0.05,$ $0.2,$ $0.3,$ and $1$ from top to bottom, obtained numerically. |

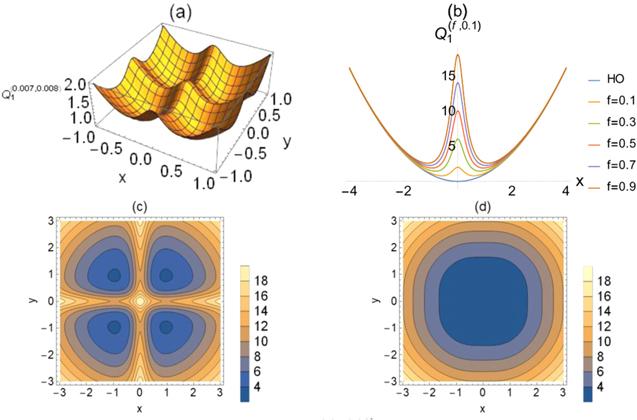

Figure 4. (a) The three-dimensional representation of the DLPs ${Q}_{1}^{(0.07,0.08)}\left(x,y\right).$ (b) The vertical cross-sections of the DLPs ${Q}_{1}^{(f,0.1)}\left(x,y\right).$ (c) and (d) are the contour plots of the potentials ${Q}_{1}^{(1,0.1)}\left(x,y\right)$ and ${Q}_{1}^{(1,1)}\left(x,y\right),$ respectively. The potential changes from four minima potential to HOP, ${H}_{1}.$ |

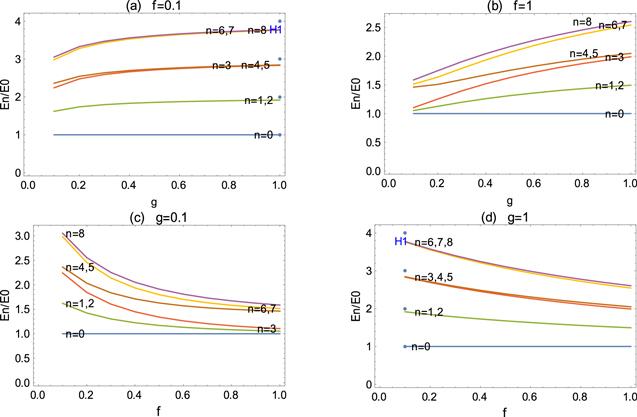

Figure 5. Representation of the first nine energy levels, as a function of $f$ and $g$ for DLPs ${Q}_{1}^{(f,g)}\left(x,y\right),$ (normalized to the ground state energy). (a) and (b) show the behavior of the spectra of the DLPs ${Q}_{1}^{(f,g)}\left(x,y\right)$ against the parameter $g$ with $f=0.1$ and $1,$ respectively. However, (c) and (d) display the spectra of the potential against the parameter $f$ with $g=0.1$ and $1,$ respectively. |

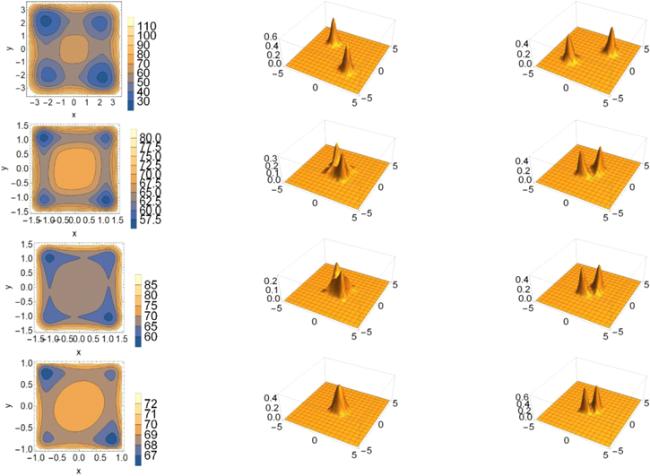

Figure 6. The contour plots of the potentials ${\Upsilon }^{(k)}\left(x,y\right)$ (left panel), the ground state probability density of the second configuration (medial panel), and the ground state probability density of the first configuration (right panel), as $k=0.05,$ $2.2,$ $3,$ and $10$ from top to bottom, obtained numerically. |

3. Non-CQOM

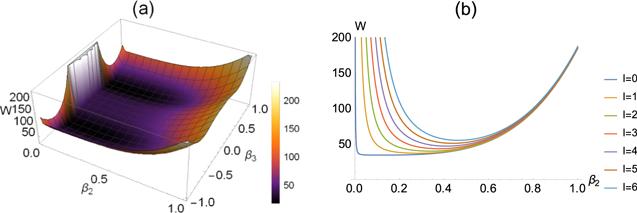

Figure 7. (a) The three-dimensional plot of the potential $W\left({\beta }_{2},{\beta }_{3},0\right).$ (b) The evolution of the vertical cross-sections of the potentials $W\left({\beta }_{2},{\beta }_{3},I\right),$ at ${\beta }_{3}=0,$ as a function of the angular momentum $I$ and ${\beta }_{2}.$ |

Table 1. Theoretical and experimental energy spectra of 100Mo [43] and 146Nd [44], normalized to the energy of the first excited 2+ state. For each nucleus, the theoretical spectra ${{\epsilon }}_{i}^{Q},$ ${{\epsilon }}_{i}^{W},$ and ${{\epsilon }}_{i}^{{\rm{\Lambda }}}$ are the results from the potentials ( |

| 100Mo | 146Nd | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ${L}^{+}$ | ${{\epsilon }}_{i}^{\exp }$ | ${{\epsilon }}_{i}^{Q}$ | ${{\epsilon }}_{i}^{W}$ | ${{\epsilon }}_{i}^{{\rm{\Lambda }}}$ | ${{\epsilon }}_{i}^{\exp }$ | ${{\epsilon }}_{i}^{Q}$ | ${{\epsilon }}_{i}^{W}$ | ${{\epsilon }}_{i}^{{\rm{\Lambda }}}$ | |

| Yrast | ${0}^{+}$ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ${2}^{+}$ | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| ${4}^{+}$ | 2.121 27 | 2.262 17 | 2.211 52 | 2.322 41 | 2.298 81 | 2.440 77 | 2.246 87 | 2.416 71 | |

| ${6}^{+}$ | 3.448 66 | 3.569 56 | 3.572 88 | 3.707 91 | 3.922 43 | 3.991 42 | 3.642 52 | 3.931 76 | |

| ${8}^{+}$ | 4.905 15 | 4.889 92 | 5.056 45 | 5.112 75 | 5.715 07 | 5.579 33 | 5.158 55 | 5.479 37 | |

| ${10}^{+}$ | (6.285 85) | (6.216 31) | (6.644 81) | (6.526 41) | 7.315 34 | 7.183 33 | 6.777 89 | 7.041 51 | |

| ${12}^{+}$ | (7.584 39) | (7.545 76) | (8.325 69) | (7.944 75) | 8.800 57 | 8.796 12 | 8.488 65 | 8.611 64 | |

| ${14}^{+}$ | (9.101 38) | (8.876 95) | (10.0899) | (9.365 87) | 10.3442 | 10.4142 | 10.2820 | 10.1867 | |

| ${16}^{+}$ | 12.0328 | 12.0355 | 12.1508 | 11.7653 | |||||

| Yrast | ${1}^{-}$ | ||||||||

| ${3}^{-}$ | 3.562 92 | 1.6204 | 1.584 62 | 1.647 13 | 2.621 42 | 1.697 97 | 1.602 24 | 1.687 77 | |

| ${5}^{-}$ | (4.368 55) | (2.913 45) | (2.875 53) | (3.011 49) | 3.3442 | 3.208 84 | 2.928 27 | 3.167 98 | |

| ${7}^{-}$ | (5.308 44) | (4.228 70) | (4.300 64) | (4.408 82) | 4.472 01 | 4.782 61 | 4.386 72 | 4.703 08 | |

| ${9}^{-}$ | (6.159 82) | (5.552 60) | (5.838 39) | (5.818 81) | 5.963 42 | 6.379 91 | 5.956 14 | 6.259 15 | |

| ${11}^{-}$ | (7.529 31) | (6.880 75) | (7.474 31) | (7.235 14) | 7.714 19 | 7.988 90 | 7.622 45 | 7.825 82 | |

| ${13}^{-}$ | (9.222 93) | (8.211 19) | (9.197 88) | (8.655 04) | 9.464 52 | 9.604 62 | 9.375 46 | 9.398 68 | |

| ${15}^{-}$ | 11.1457 | 11.2245 | 11.2073 | 10.9756 | |||||

| Non-yrast | ${2}^{+}$ | 1.297 80 | 1.183 20 | 0.680 92 | 2.212 67 | 2.017 19 | 1.445 47 | 0.686 05 | 2.458 43 |

| ${4}^{+}$ | 2.733 20 | 1.609 49 | 1.146 30 | 2.625 27 | 2.871 75 | 2.444 63 | 1.686 05 | 3.457 11 | |

| ${6}^{+}$ | (3.307 32) | (2.182 94) | (1.680 92) | (3.211 91) | 3.845 75 | 3.886 04 | 2.932 92 | 4.874 89 | |

| $2{B}_{2}/{\hslash }^{2}$ | 2.000 00 | 12.0000 | 1.500 00 | 0.900 00 | 7.000 00 | 1.000 00 | |||

| Δ | 0.779 32 | 0.835 37 | 0.708 31 | 0.463 95 | 0.628 83 | 0.542 15 | |||

| 148Nd | 148Sm | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L+ | ${{\epsilon }}_{i}^{\exp }$ | ${{\epsilon }}_{i}^{Q}$ | ${{\epsilon }}_{i}^{W}$ | ${{\epsilon }}_{i}^{{\rm{\Lambda }}}$ | ${{\epsilon }}_{i}^{\exp }$ | ${{\epsilon }}_{i}^{Q}$ | ${{\epsilon }}_{i}^{W}$ | ${{\epsilon }}_{i}^{{\rm{\Lambda }}}$ | |

| Yrast | ${0}^{+}$ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ${2}^{+}$ | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| ${4}^{+}$ | 2.493 54 | 2.553 08 | 2.502 60 | 2.416 71 | 2.144 83 | 2.236 68 | 2.1853 | 2.238 27 | |

| ${6}^{+}$ | 4.241 96 | 4.268 11 | 4.213 86 | 3.931 76 | 3.463 38 | 3.511 07 | 3.526 06 | 3.513 97 | |

| ${8}^{+}$ | 6.152 47 | 6.045 56 | 6.064 29 | 5.479 37 | 4.933 67 | 4.796 40 | 4.993 45 | 4.801 10 | |

| ${10}^{+}$ | (8.190 92) | (7.850 48) | (8.027 51) | (7.041 51) | 6.175 00 | 6.086 76 | 6.568 94 | 6.093 38 | |

| ${12}^{+}$ | (10.2957) | (9.670 09) | (10.0889) | (8.611 64) | 7.458 48 | 7.379 64 | 8.239 52 | 7.388 34 | |

| ${14}^{+}$ | 8.731 96 | 8.673 94 | 9.995 50 | 8.684 87 | |||||

| ${16}^{+}$ | 9.988 01 | 9.969 14 | 11.8294 | 9.982 40 | |||||

| Yrast | ${1}^{-}$ | 3.391 45 | 0.378 19 | 0.391 79 | 0.397 02 | ||||

| ${3}^{-}$ | 3.312 33 | 1.744 68 | 1.717 02 | 1.687 77 | 2.110 67 | 1.609 20 | 1.570 78 | 1.610 30 | |

| ${5}^{-}$ | 4.117 67 | 3.398 94 | 3.338 22 | 3.167 98 | 2.896 97 | 2.871 87 | 2.838 37 | 2.874 01 | |

| ${7}^{-}$ | 5.450 78 | 5.152 03 | 5.123 77 | 4.703 08 | 3.868 07 | 4.152 85 | 4.245 25 | 4.156 64 | |

| ${9}^{-}$ | 7.065 96 | 6.945 65 | 7.032 86 | 6.259 15 | 5.101 58 | 5.441 16 | 5.768 59 | 5.446 80 | |

| ${11}^{-}$ | (8.871 06) | (8.758 89) | (9.046 62) | (7.825 82) | 6.568 78 | 6.732 97 | 7.393 01 | 6.740 62 | |

| ${13}^{-}$ | (10.8300) | (10.5835) | (11.1532) | (9.398 68) | 7.991 64 | 8.026 65 | 9.107 35 | 8.036 45 | |

| ${15}^{-}$ | 9.333 27 | 9.321 45 | 10.9031 | 9.333 53 | |||||

| Non-yrast | ${2}^{+}$ | 3.039 11 | 1.640 91 | 0.785 20 | 2.458 43 | 2.588 59 | 1.149 78 | 0.684 21 | 2.014 85 |

| ${4}^{+}$ | 3.881 34 | 2.639 76 | 1.785 16 | 3.457 11 | 3.015 45 | 2.149 59 | 1.684 21 | 3.014 55 | |

| ${6}^{+}$ | 5.316 87 | 4.193 52 | 3.287 79 | 4.874 89 | 3.443 21 | 3.386 47 | 2.869 51 | 4.253 16 | |

| $2{B}_{2}/{\hslash }^{2}$ | 0.6000 | 1.200 00 | 1.000 00 | 2.300 00 | 26.0000 | 2.300 00 | |||

| Δ | 0.829 121 | 0.905 12 | 0.966 31 | 0.485 58 | 0.862 96 | 0.424 24 | |||

| 150Sm | 220Ra | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ${L}^{+}$ | ${{\epsilon }}_{i}^{\exp }$ | ${{\epsilon }}_{i}^{Q}$ | ${{\epsilon }}_{i}^{W}$ | ${{\epsilon }}_{i}^{{\rm{\Lambda }}}$ | ${{\epsilon }}_{i}^{\exp }$ | ${{\epsilon }}_{i}^{Q}$ | ${{\epsilon }}_{i}^{W}$ | ${{\epsilon }}_{i}^{{\rm{\Lambda }}}$ | |

| Yrast | ${0}^{+}$ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ${2}^{+}$ | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| ${4}^{+}$ | 2.315 57 | 2.472 05 | 2.361 23 | 2.416 71 | 2.297 48 | 2.553 08 | 2.432 83 | 2.393 24 | |

| ${6}^{+}$ | 3.829 04 | 4.067 41 | 3.886 13 | 3.931 76 | 3.854 90 | 4.268 11 | 4.049 04 | 3.875 43 | |

| ${8}^{+}$ | 5.500 00 | 5.706 27 | 5.534 38 | 5.479 37 | 5.608 96 | 6.045 56 | 5.794 85 | 5.386 40 | |

| ${10}^{+}$ | 7.285 03 | 7.363 85 | 7.287 12 | 7.041 51 | 7.522 13 | 7.850 48 | 7.648 49 | 6.910 28 | |

| ${12}^{+}$ | 9.126 95 | 9.031 62 | 9.132 18 | 8.611 64 | 9.586 55 | 9.670 09 | 9.596 82 | 8.441 20 | |

| ${14}^{+}$ | 11.0057 | 10.7055 | 11.0607 | 10.1867 | 11.7966 | 11.4987 | 11.6306 | 9.976 41 | |

| ${16}^{+}$ | 13.1326 | 12.3834 | 13.0658 | 11.7653 | 14.1373 | 13.3332 | 13.7428 | 11.5146 | |

| ${18}^{+}$ | 16.5933 | 15.1718 | 15.9278 | 13.0552 | |||||

| Yrast | ${1}^{-}$ | (2.313 73) | (0.378 20) | (0.404 39) | (0.400 87) | ||||

| ${3}^{-}$ | 3.207 78 | 1.711 20 | 1.655 40 | 1.687 77 | (2.656 58) | (1.744 68) | (1.686 97) | (1.677 74) | |

| ${5}^{-}$ | 4.064 97 | 3.261 34 | 3.106 63 | 3.167 98 | (3.556 30) | (3.398 94) | (3.222 72) | (3.128 80) | |

| ${7}^{-}$ | 5.284 13 | 4.883 60 | 4.696 23 | 4.703 08 | (4.890 76) | (5.152 03) | (4.907 40) | (4.628 72) | |

| ${9}^{-}$ | 6.683 83 | 6.533 41 | 6.398 55 | 6.259 15 | (6.519 89) | (6.945 65) | (6.709 13) | (6.147 20) | |

| ${11}^{-}$ | 8.216 77 | 8.196 77 | 8.198 72 | 7.825 82 | (8.381 51) | (8.758 89) | (8.611 46) | (7.675 08) | |

| ${13}^{-}$ | 9.860 18 | 9.867 98 | 10.0865 | 9.398 68 | (10.4409) | (10.5835) | (10.6035) | (9.208 37) | |

| ${15}^{-}$ | 11.7189 | 11.5441 | 12.0541 | 10.9756 | (12.6751) | (12.4153) | (12.6773) | (10.7452) | |

| ${17}^{-}$ | (15.0706) | (14.2520) | (14.8265) | (12.2846) | |||||

| Non-yrast | ${2}^{+}$ | 2.217 07 | 2.496 15 | 1.721 49 | 3.457 11 | ||||

| ${4}^{+}$ | 3.132 04 | 3.968 87 | 3.082 73 | 4.874 89 | |||||

| $2{B}_{2}/{\hslash }^{2}$ | 0.800 00 | 2.600 00 | 1.000 00 | 0.600 00 | 1.700 00 | 1.100 00 | |||

| Δ | 0.593 81 | 0.529 96 | 0.810 63 | 0.719 99 | 0.574 23 | 1.072 01 | |||

| 220Rn | 220Th | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ${L}^{+}$ | ${{\epsilon }}_{i}^{\exp }$ | ${{\epsilon }}_{i}^{Q}$ | ${{\epsilon }}_{i}^{W}$ | ${{\epsilon }}_{i}^{{\rm{\Lambda }}}$ | ${{\epsilon }}_{i}^{\exp }$ | ${{\epsilon }}_{i}^{Q}$ | ${{\epsilon }}_{i}^{W}$ | ${{\epsilon }}_{i}^{{\rm{\Lambda }}}$ | |

| Yrast | ${0}^{+}$ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ${2}^{+}$ | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| ${4}^{+}$ | 2.214 52 | 2.413 83 | 2.201 39 | 2.416 71 | 2.652 01 | 2.390 34 | 2.204 27 | 2.372 51 | |

| ${6}^{+}$ | (3.626 14) | (3.926 53) | (3.553 91) | (3.931 76) | 4.069 81 | 3.870 33 | 3.559 24 | 3.826 03 | |

| ${8}^{+}$ | (5.163 07) | (5.471 61) | (5.029 76) | (5.479 37) | 5.578 36 | 5.378 80 | 5.037 17 | 5.305 25 | |

| ${10}^{+}$ | (6.768 05) | (7.030 76) | (6.611 25) | (7.041 51) | 7.025 13 | 6.899 77 | 6.620 47 | 6.796 08 | |

| ${12}^{+}$ | (8.439 42) | (8.597 60) | (8.285 93) | (8.611 64) | 8.523 21 | 8.427 56 | 8.296 74 | 8.293 19 | |

| ${14}^{+}$ | (10.1772) | (10.1690) | (10.0445) | (10.1867) | 10.0698 | 9.959 36 | 10.0567 | 9.794 08 | |

| ${16}^{+}$ | (11.9793) | (11.7433) | (11.8796) | (11.7653) | 11.7850 | 11.4937 | 11.8931 | 11.2975 | |

| ${18}^{+}$ | (13.7979) | (13.3196) | (13.7854) | (13.3468) | 13.4977 | 13.0297 | 13.8001 | 12.8031 | |

| ${20}^{+}$ | (15.6178) | (14.8973) | (15.7571) | (14.9314) | 15.0771 | 14.5670 | 15.7729 | 14.3106 | |

| Yrast | ${1}^{-}$ | 2.669 71 | 0.397 09 | 0.470 03 | 0.397 02 | ||||

| ${3}^{-}$ | 2.751 04 | 1.686 46 | 1.579 42 | 1.687 77 | |||||

| ${5}^{-}$ | (3.534 85) | (3.163 84) | (2.860 83) | (3.167 98) | 3.468 76 | 3.124 75 | 2.864 98 | 3.094 33 | |

| ${7}^{-}$ | (4.681 33) | (4.696 66) | (4.277 69) | (4.703 08) | 4.638 74 | 4.622 44 | 4.284 09 | 4.563 66 | |

| ${9}^{-}$ | (6.066 80) | (6.249 93) | (5.808 17) | (6.259 15) | 5.999 65 | 6.138 18 | 5.816 51 | 6.049 64 | |

| ${11}^{-}$ | (7.609 96) | (7.813 46) | (7.437 58) | (7.825 82) | 7.535 43 | 7.663 04 | 7.447 62 | 7.544 05 | |

| ${13}^{-}$ | (9.241 08) | (9.382 87) | (9.155 21) | (9.398 68) | 8.918 67 | 9.193 08 | 9.166 75 | 9.043 25 | |

| ${15}^{-}$ | (10.9473) | (10.9559) | (10.9529) | (10.9756) | 10.4880 | 10.7263 | 10.9658 | 10.5455 | |

| ${17}^{-}$ | (12.7328) | (12.5312) | (12.8240) | (12.5557) | 12.1019 | 12.2615 | 12.8381 | 12.0501 | |

| ${19}^{-}$ | (14.5635) | (14.1083) | (14.7633) | (14.1387) | 13.8000 | 13.7983 | 14.7785 | 13.5566 | |

| ${21}^{-}$ | (16.4378) | (15.6865) | (16.7663) | (15.7250) | |||||

| $2{B}_{2}/{\hslash }^{2}$ | 1.000 00 | 15.0000 | 1.000 00 | 1.100 00 | 14.0000 | 1.200 00 | |||

| Δ | 0.630 22 | 0.556 52 | 0.627 32 | 0.444 85 | 0.620 04 | 0.498 08 | |||

| 222Rn | 222Th | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ${L}^{+}$ | ${{\epsilon }}_{i}^{\exp }$ | ${{\epsilon }}_{i}^{Q}$ | ${{\epsilon }}_{i}^{W}$ | ${{\epsilon }}_{i}^{{\rm{\Lambda }}}$ | ${{\epsilon }}_{i}^{\exp }$ | ${{\epsilon }}_{i}^{Q}$ | ${{\epsilon }}_{i}^{W}$ | ${{\epsilon }}_{i}^{{\rm{\Lambda }}}$ | |

| Yrast | ${0}^{+}$ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ${2}^{+}$ | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| ${4}^{+}$ | 2.408 16 | 2.632 37 | 2.508 07 | 2.393 24 | 2.399 35 | 2.613 24 | 2.485 67 | 2.393 24 | |

| ${6}^{+}$ | (4.127 28) | (4.471 30) | (4.227 00) | (3.875 43) | 4.091 65 | 4.421 55 | 4.173 37 | 3.875 43 | |

| ${8}^{+}$ | (6.058 54) | (6.395 41) | (6.086 01) | (5.386 40) | 5.965 63 | 6.309 13 | 5.997 56 | 5.386 40 | |

| ${10}^{+}$ | (8.125 67) | (8.358 83) | (8.058 28) | (6.910 28) | 7.971 09 | 8.232 81 | 7.933 18 | 6.910 28 | |

| ${12}^{+}$ | (10.2760) | (10.3431) | (10.1290) | (8.441 20) | 10.0966 | 10.1757 | 9.966 02 | 8.441 20 | |

| ${14}^{+}$ | (12.4447) | (12.3403) | (12.2884) | (9.976 41) | 12.3279 | 12.1303 | 12.0864 | 9.976 41 | |

| ${16}^{+}$ | (14.6493) | (14.3460) | (14.5288) | (11.5146) | 14.6634 | 14.0928 | 14.2870 | 11.5146 | |

| ${18}^{+}$ | 17.0949 | 16.0609 | 16.5621 | 13.0552 | |||||

| Yrast | ${1}^{-}$ | 3.226 10 | 0.369 99 | 0.390 91 | 0.400 87 | ||||

| ${3}^{-}$ | 3.411 92 | 1.776 19 | 1.719 35 | 1.677 74 | 2.547 74 | 1.768 71 | 1.709 79 | 1.677 74 | |

| ${5}^{-}$ | (4.284 64) | (3.536 43) | (3.347 36) | (3.128 80) | 3.551 55 | 3.502 96 | 3.310 01 | 3.128 80 | |

| ${7}^{-}$ | (5.634 80) | (5.426 52) | (5.141 12) | (4.628 72) | 5.038 19 | 5.359 05 | 5.070 37 | 4.628 72 | |

| ${9}^{-}$ | (7.287 33) | (7.373 73) | (7.059 07) | (6.147 20) | 6.848 34 | 7.267 86 | 6.952 47 | 6.147 20 | |

| ${11}^{-}$ | (9.174 01) | (9.349 01) | (9.082 05) | (7.675 08) | 8.852 15 | 9.202 43 | 8.938 13 | 7.675 08 | |

| ${13}^{-}$ | (11.2197) | (11.3404) | (11.1981) | (9.208 37) | 10.9956 | 11.1518 | 11.0157 | 9.208 37 | |

| ${15}^{-}$ | (13.3475) | (13.3422) | (13.3988) | (10.7452) | 13.2646 | 13.1107 | 13.1770 | 10.7452 | |

| ${17}^{-}$ | (15.4774) | (15.3513) | (15.6777) | (12.2846) | 15.6738 | 15.0763 | 15.4155 | 12.2846 | |

| ${19}^{-}$ | (17.6472) | (17.3659) | (18.0295) | (13.8264) | |||||

| ${21}^{-}$ | (19.8502) | (19.3850) | (20.4501) | (15.3708) | |||||

| $2{B}_{2}/{\hslash }^{2}$ | 0.460 00 | 1.170 00 | 1.100 00 | 0.490 00 | 1.300 00 | 1.100 00 | |||

| Δ | 0.661 79 | 0.659 05 | 1.358 38 | 0.586 92 | 0.432 97 | 1.196 41 | |||

Table 6. The parameters of the potentials ${\rm{\Lambda }}\left({\beta }_{2},{\beta }_{3},I\right),$ $W\left({\beta }_{2},{\beta }_{3},I\right)$ and $Q\left({\beta }_{2},{\beta }_{3},I\right)$ are ${B}_{3},$ ${d}_{2},$ and ${d}_{3}$ (in ${\hslash }^{2}$ MeV−1), ${d}_{0}\,$(in ${\hslash }^{2}$), ${C}_{21}$ and ${C}_{31}$ (in MeV), ${C}_{22}={C}_{32}$ = 1 MeV, whereas ${C}_{23}$ and ${C}_{33}$ are dimensionless, ${C}_{23}=1.$ |

| $2{B}_{3}/{\hslash }^{2}$ | ${C}_{21}$ | ${C}_{31}$ | ${C}_{33}$ | ${d}_{2}$ | ${d}_{3}$ | ${d}_{0}$ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ${\rm{\Lambda }}\left({\beta }_{2},{\beta }_{3},I\right)$ | 1 | 300 | 240 | — | 6 | 0.0005 | 0.1 |

| $W\left({\beta }_{2},{\beta }_{3},I\right)$ | 1 | 300 | 200 | 0.03 | 7 | 0.000 02 | 0.01 |

| $Q\left({\beta }_{2},{\beta }_{3},I\right)$ | 0.4 | 300 | 240 | 0.015 | 6 | 0.0002 | 0.1 |

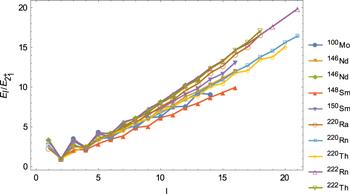

Figure 8. Experimental energy ratios ${E}_{{I}^{\pi }}/{E}_{{2}_{1}^{+}}$ for states of the positive-parity ground state band ($I$ even) and the lowest negative-parity band ($I$ odd), as functions of the angular momentum $I,$ for 100Mo [43], 146Nd [44], 148Nd [46], 148Sm [46], 150Sm [47], 220Ra [48], 220Rn [48], 220Th [48], 222Rn [49] and 222Th [49]. |

Figure 9. The contour plots of the ground state wave functions of 100Mo, 146,148Nd, 148,150Sm, 220Ra, 220,222Rn, and 220,222Th using the potential ( |