1. Introduction

2. Setup

Figure 1. (Color online) (a) Potential photon-phonon-spin hybrid setup with respect to the triple coupling system mediated by a squeezed mechanical mode. A sharp nano magnetic tip is attached at the end of the silicon cantilever with its tunable spring constant, above which a single NV center is set near to this magnet. A superconducting coplanar MW cavity also couples to this mechanical cantilever through capacitive interactions. As a result, it is available for this MR to achieve capacitive coupling to the MW cavity and magnetic coupling to the single NV spin, respectively. (b) Schematic of enhancing the indirect coupling between the MW cavity and single NV spin through MPA. (c) Ground-state energy diagram for a single NV center in the basis of bare state and dressed state. |

3. Mechanism of this triple coupling system

In equation (

Here, we define ω0 ≡ ωdg, ${\hat{\sigma }}_{z}\equiv {\hat{\sigma }}_{{dd}}-{\hat{\sigma }}_{{gg}}$, and ${\hat{\sigma }}^{\pm }\equiv {\hat{\sigma }}_{{dg}}^{\pm }$ for simplicity.

In equation (

in which the parameters are assumed as δc = ωc − ωL, $\alpha$* = $\alpha$, and g = g0$\alpha$, and we have set $\delta {\hat{a}}^{(\dagger )}\equiv {\hat{a}}^{(\dagger )}$ for simplicity.

Then, we apply an unitary transformation ${\hat{U}}_{0}=\exp [{\rm{i}}{\hat{H}}_{0}t]$ to equation (

with δm = ωm − ωχ, Δc = δc − ωχ, and Δq = ω0 − ωχ.

with ${{\rm{\Delta }}}_{m}={\delta }_{m}/\cosh 2r$. Here, it is noted that we have omitted the weak disturbance items during this diagonalization process, because of their diminishing coefficients (∝ e−r) as we increase the squeezing parameter r. In the interaction picture (IP), we obtain

with G1 = ger, G2 = λer, δ1 = Δc + Δm, δ2 = Δc − Δm, δ3 = Δq + Δm, and δ4 = Δq − Δm. For a realistic condition, the dynamical evolution of this hybrid system is dominated by the master equation effectively as follows:

where ${ \mathcal D }[\hat{o}]\hat{\rho }=\hat{o}\hat{\rho }{\hat{o}}^{\dagger }-\hat{\rho }{\hat{o}}^{\dagger }\hat{o}/2-{\hat{o}}^{\dagger }\hat{o}\hat{\rho }/2$, $\hat{\rho }$ is the density matrix of this three-body quantum system, and κ1, ${\kappa }_{\mathrm{eff}}^{S}$, and γ correspond to the MW cavity dissipation rate, the effective squeezed MR damping rate, and the NV dephasing rate, respectively.

4. Applications

4.1. Efficiency improvement on quantum state transfer between the NV spin and MW photon

Utilizing this interaction, we can implement the target of quantum state transfer from the MW photons to an NV spin mediated by this squeezed phonon mode, and vice versa [39, 40]. Therefore, the first application of this scheme is focused on establishing a quantum spin-photon interface with further improved efficiency.

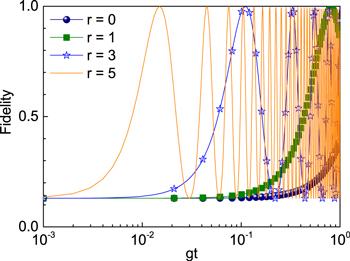

Figure 2. (Color online) Dynamical fidelity for this photon-spin state transfer process. The parameters are set as g = λ, r = 0 the black solid line with solid spheres, r = 1 the olive solid line with solid squares, r = 3 the blue solid line with open stars, and r = 5 the orange solid line, κ1 ∼ γ ∼ 0.01g, and ${\kappa }_{\mathrm{eff}}^{S}\sim 0.1g$. |

4.2. Engineering NV spin and MW photon into the quantum correlated state indirectly by the squeezed phonon mode

or

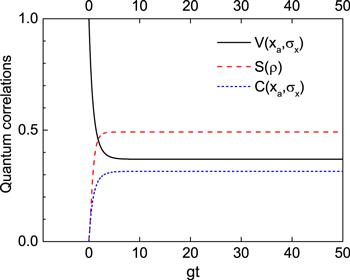

Dominated by both types of triple interactions, we can also carry out the task of engineering the MW photon and NV spin into the steady nonclassical state, utilizing different routes such as the adiabatic evolution or fast dissipation, etc [38, 52, 57-60]. Taking Hamiltonian (11) as an example, we first assume G1 is opposite to G2 in phase and G1 ≠ G2; then, we can rewrite this Hamiltonian as ${\hat{H}}_{(\mathrm{ii})}^{S(1)}\simeq \hat{b}({G}_{2}{\hat{\sigma }}^{+}-{G}_{1}\hat{a})+{\rm{h}}.{\rm{c}}.$. We note this type of interaction is quite similar to the general Hamiltonian for engineering the two-mode quantum correlated state assisted by fast dissipation [60-63]. In this scheme, we stress that the photon-phonon and spin-phonon coupling can be exponentially enhanced in a squeezed frame; however, the realistic dissipation rate of this squeezed phonon mode will be inevitably amplified without any additional cooling design. To engineer this pair of NV and MW photon into the relevant nonclassical state, we are confident that the fast dissipation route is a more suitable choice in this scheme.

Figure 3. (Color online) Time-dependent quantum correlations of the MW photon and NV spin. The parameters are set as λ = − 0.7g, r = 2, κ1 ∼ γ ∼ 0.01g, and ${\kappa }_{\mathrm{eff}}^{S}\sim 200g$, where the black solid line means the joint variance $V({\hat{X}}_{a},{\hat{\sigma }}_{x})$, the red dashed line means the VNE $S(\hat{\varrho })$, and the blue short dashed line means the quantum correlation $C({\hat{X}}_{a},{\hat{\sigma }}_{x})$. |

5. Experimental estimations

6. Conclusion

Appendix A. Realizing the second-order nonlinear interaction of this MRAppendix B. Magnetic coupling of the MR to an NV center in the dressed-state basis

where $\hat{z}$ and ${\hat{p}}_{z}$ are the displacement and momentum operators in the z direction, m means the effective mass of this MR, and ${k}_{0}={\omega }_{m}^{2}m$ and ${k}_{\chi }(t)={\rm{\Delta }}k\cos 2{\omega }_{\chi }t$ correspond to the unperturbed fundamental spring constant (the fundamental frequency ωm) and the time-varying spring constant, respectively. We also state that Δk is the variation of the spring constant. Applying the definition of the displacement operator $\hat{z}={z}_{{zf}}({\hat{b}}^{\dagger }+\hat{b})$ and the zero-field quantum fluctuation ${z}_{{zf}}=\sqrt{{\hslash }/2m{\omega }_{m}}$, we can quantize the MR’s Hamiltonian ${\hat{H}}_{\mathrm{mr}}$ as (ℏ = 1),

where ${{\rm{\Omega }}}_{\chi }=-{\rm{\Delta }}{{kz}}_{\mathrm{zf}}^{2}/2$ is the second-order nonlinear drive amplitude.

where λ0 = $\mu$BgeGmzzf is the magnetic coupling strength with the Bohr magneton $\mu$B = 14 GHz/T, the NV Landé factor ge ≃ 2, and the first-order magnetic field gradient Gm = ∂Bz/∂z. As illustrated in figure 1(c), in the bare-state basis, we can not achieve the effective spin-phonon transition interaction because of ωm ≪ D ± δ/2, but we can utilize the dressed-state method to resolve this problem.

where Δ± ≡ ∣D − ω± ± δ/2∣ and ${{\rm{\Omega }}}_{\pm }\equiv {g}_{e}{\mu }_{B}{B}_{0x}^{\pm }/\sqrt{2}$. For simplicity, we set Δ± = Δ and Ω± = Ω in the following discussions. The Hamiltonian (A1) couples the state ∣0⟩ to a 'bright'state $| b\rangle =(| +1\rangle +| -1\rangle )/\sqrt{2}$, while the 'dark'state $| d\rangle =(| +\rangle -| -\rangle )/\sqrt{2}$ is decoupled. The resulting eigen basis of ${\hat{H}}_{\mathrm{NV}}$ is therefore given by ∣d⟩ and the two dressed states $| g\rangle =\cos \theta | 0\rangle -\sin \theta | b\rangle $ and $| e\rangle =\cos \theta | b\rangle +\sin \theta | 0\rangle $, with the definition $\tan (2\theta )\,=-\sqrt{2}{\rm{\Omega }}/{\rm{\Delta }}$. In this dressed basis, we acquire the eigenfrequencies: ωd = − Δ, and ${\omega }_{e/g}=(-{\rm{\Delta }}\pm \sqrt{{{\rm{\Delta }}}^{2}+2{{\rm{\Omega }}}^{2}})/\sqrt{2}$. The energy-level diagram of the bare states and the dressed states are both illustrated in figure 1(c). With the purpose of building a efficient spin-phonon transition passage, we stress that its parameters Ω and Δ are tunable here, and then we can obtain the available energy levels to match the frequency ωm of this MR. Therefore, under the rotating wave approximation, we can rewrite the spin-phonon Hamiltonian from equations (

where the parameters are expressed as ωe ≡ ωe − ωg, ωd ≡ ωd − ωg, ${\hat{\sigma }}_{\mathrm{ee}}\equiv | e\rangle \langle e| $, ${\hat{\sigma }}_{\mathrm{dd}}\equiv | d\rangle \langle d| $, ${\hat{\sigma }}_{\mathrm{gg}}\equiv | g\rangle \langle g| $, ${\hat{\sigma }}_{\mathrm{dg}}^{-}\equiv | g\rangle \langle d| $, ${\hat{\sigma }}_{\mathrm{ed}}^{-}\equiv | d\rangle \langle e| $, ${\lambda }_{d}=-{\lambda }_{0}\sin \theta $, and ${\lambda }_{e}\,={\lambda }_{0}\cos \theta $.