1. Introduction

2. Computational details

2.1. Ab initio calculations

2.2. Potential energy functions

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Analytical potential energy functions

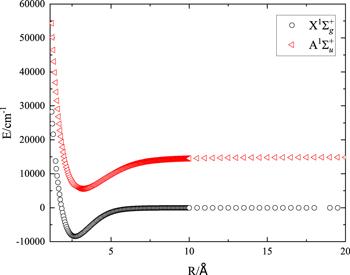

Figure 1. The ab initio energy points for the ${\rm{X}}{}^{{\rm{1}}}{\rm{\Sigma }}_{g}^{+}$ and ${\rm{A}}{}^{{\rm{1}}}{\rm{\Sigma }}_{u}^{+}$ states of the lithium dimer under the calculation of MRCI/AV5Z. |

Table 1. The fitting parameters of the MS analytical potential energy functions for the ${\rm{X}}{}^{{\rm{1}}}{\rm{\Sigma }}_{g}^{+}$ state based on MRCI/AVXZ (X = T, Q, 5) and the ${\rm{A}}{}^{{\rm{1}}}{\rm{\Sigma }}_{u}^{+}$ state based on MRCI/AV5Z. The corresponding ab initio calculation values for Re and De are listed in the parentheses. |

| Potential parameters | AVTZ ${\rm{X}}{}^{{\rm{1}}}{\rm{\Sigma }}_{g}^{+}$ | AVQZ ${\rm{X}}{}^{{\rm{1}}}{\rm{\Sigma }}_{g}^{+}$ | AV5Z ${\rm{X}}{}^{{\rm{1}}}{\rm{\Sigma }}_{g}^{+}$ | AV5Z ${\rm{A}}{}^{{\rm{1}}}{\rm{\Sigma }}_{u}^{+}$ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Re/Å | 2.6994 (2.6989) | 2.6976 (2.6978) | 2.6974 (2.6977) | 3.1421 (3.1401) |

| De/cm−1 | 8337.5346 (8338.6302) | 8414.9678 (8416.1149) | 8428.0893 (8429.2647) | 9291.0809 (9290.2886) |

| a1/Å−1 | 2.1776 | 2.1742 | 2.1729 | 1.5266 |

| a2/Å−2 | 1.6309 | 1.6239 | 1.6214 | 0.8087 |

| a3/Å−3 | 0.6373 | 0.6320 | 0.6305 | 0.2635 |

| a4/Å−4 | 0.1171 | 0.1149 | 0.1146 | 0.05164 |

| a5/Å−5 | −0.027 57 | −0.028 35 | −0.028 30 | 0.009 509 |

| a6/Å−6 | −0.014 67 | −0.014 37 | −0.014 34 | 0.000 7928 |

| a7/Å−7 | 0.002 564 | 0.002 635 | 0.002 566 | −0.002 086 |

| a8/Å−8 | 0.001 453 | 0.001 395 | 0.001 388 | 0.000 1562 |

| a9/Å−9 | 0.000 1205 | 0.000 1292 | 0.000 1395 | 0.000 2391 |

| a10/Å−10 | −0.000 1254 | −0.000 1253 | −0.000 1269 | −0.000 050 66 |

| a11/Å−11 | 0.000 013 69 | 0.000 013 57 | 0.000 013 62 | 0.000 003 274 |

| RMS/cm−1 | 0.7672 | 0.8006 | 0.8166 | 2.7880 |

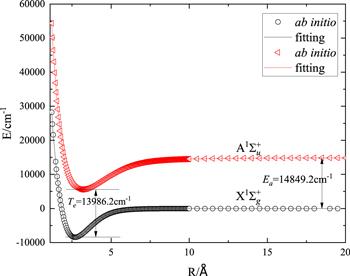

Figure 2. Ab initio points and fitting curves for the ${\rm{X}}{}^{{\rm{1}}}{\rm{\Sigma }}_{g}^{+}$ and ${\rm{A}}{}^{{\rm{1}}}{\rm{\Sigma }}_{u}^{+}$ states of Li2 under MRCI/AV5Z; Ea is the atomic excitation energy and Te is the adiabatic excitation energy. |

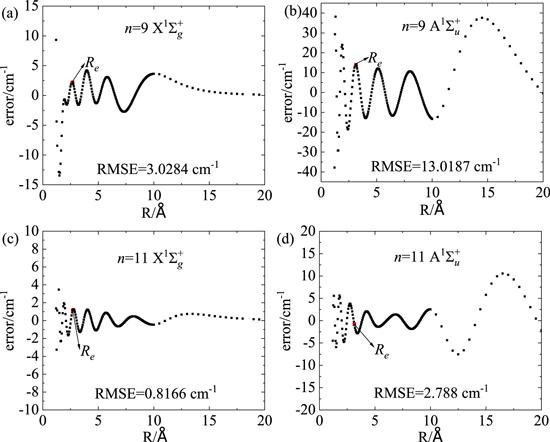

Figure 3. Fitting errors of the PECs for the ground state (a) and the first state (b) of Li2 with n = 9; fitting errors of the PECs for the ground state (c) and the first state (d) of Li2 with n = 11. |

Table 2. Equilibrium bond lengths Re (Å), potential well depth De (cm−1) and spectroscopic constants (cm−1) for the ground state ${\rm{X}}{}^{{\rm{1}}}{\rm{\Sigma }}_{g}^{+}$ of Li2. |

| Basis/References | Re/Å | De/cm−1 | ωe/cm−1 | Be/cm−1 | ωeχe/cm−1 | αe/cm−1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AV5Z | 2.6974 | 8428.089 | 347.9251 | 0.661 04 | 2.4932 | 0.006 956 |

| Exp. [21] | 2.6734 | 8549.473 | 351.422 95 | 0.668 24 | 2.4417 | — |

| Exp. [30] | 2.673 | 8549.473 | 351.4 | 0.673 | 2.61 | 0.0068 |

| Theory [18] | 2.658 | 8613 | 352.41 | — | — | — |

| Theory [34] | 2.660 | 8510 | 353.0 | — | — | — |

| Theory [35] | 2.675 | 8466 | 351.01 | — | — | — |

| Theory [19] | 2.752 | 7856.64 | 352.50 | 0.675 | 2.70 | — |

| Theory [14] | 2.677 | 8466 | 351.0 | — | — | — |

| Theory [38] | 2.677 | 8065.541 | 351.9 | 0.671 | 2.56 | 0.0073 |

| Theory [39] | 2.7146 | 7307.38 | 327.50 | 0.668 24 | 2.651 47 | 0.006 50 |

| Theory [33] | 2.692 | 8297 | 347.1 | — | 3.6 | — |

Table 3. Equilibrium bond lengths Re (Å), potential well depth De (cm−1) and spectroscopic constants (cm−1) for the state ${\rm{A}}{}^{{\rm{1}}}{\rm{\Sigma }}_{u}^{+}$ of Li2. |

| Basis/References | Re/Å | De/cm−1 | ωe/cm−1 | Be/cm−1 | ωeχe/cm−1 | αe/cm−1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AV5Z | 3.142 | 9291.0809 | 253.704 | 0.487 | 1.511 | 0.005 02 |

| Exp. [32] | 3.108 | 9353.6079 | 255.47 | 0.498 | 1.581 | 0.005 48 |

| Theory [36] | 3.133 | 9366.5127 | 251.97 | 0.490 | 1.623 | 0.005 35 |

| Theory [34] | 3.094 | 9466 | 257.4 | — | — | — |

| Theory [33] | 3.13 | 9299 | 254 | — | 1.7 | — |

| Theory [40] | 3.072 | 9651.226 | 261.3 | — | 1.77 | — |

| Theory [14] | 3.112 | 9356 | 255 | — | — | — |

| Theory [18] | 3.092 | 9483 | 257.54 | — | — | — |

3.2. Vibrational levels and FCF

Table 4. The eigenenergies of vibrational levels for the ground state ${\rm{X}}{}^{{\rm{1}}}{\rm{\Sigma }}_{g}^{+}$ of Li2, relative to the bottom of the potential well (cm−1). |

| Vibrational levels | 7Li2 | Exp. of 7Li2 [21] | δ | 6Li2 | 6Li7Li |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 173.945 07 | 175.032 | 0.62% | 180.945 46 | 187.679 75 |

| 1 | 514.991 96 | 521.2611 | 1.20% | 535.682 43 | 555.5745 |

| 2 | 851.009 63 | 862.2642 | 1.31% | 884.9692 | 917.597 74 |

| 3 | 1181.955 78 | 1197.9974 | 1.34% | 1228.757 25 | 1273.694 39 |

| 4 | 1507.7793 | 1528.4128 | 1.35% | 1566.987 78 | 1623.797 43 |

| 5 | 1828.420 39 | 1853.4573 | 1.35% | 1899.5918 | 1967.8281 |

| 6 | 2143.810 68 | 2173.0721 | 1.35% | 2226.490 22 | 2305.695 88 |

| 7 | 2453.873 11 | 2487.1914 | 1.34% | 2547.593 81 | 2637.298 48 |

| 8 | 2758.521 94 | 2795.7419 | 1.33% | 2862.803 03 | 2962.521 61 |

| 9 | 3057.6625 | 3090.6412 | 1.07% | 3172.007 88 | 3281.238 74 |

| 10 | 3351.191 03 | 3395.7978 | 1.31% | 3475.087 47 | 3593.310 57 |

| 11 | 3638.994 29 | 3687.1094 | 1.30% | 3771.909 67 | 3898.584 58 |

| 12 | 3920.949 17 | 3972.4624 | 1.30% | 4062.330 54 | 4196.894 17 |

| 13 | 4196.922 17 | 4251.7309 | 1.29% | 4346.193 57 | 4488.057 89 |

| 14 | 4466.768 81 | 4524.7756 | 1.28% | 4623.328 95 | 4771.878 24 |

| 15 | 4730.3328 | 4791.4274 | 1.28% | 4893.552 49 | 5048.140 41 |

| 16 | 4987.445 23 | 5051.5343 | 1.27% | 5156.664 47 | 5316.610 74 |

| 17 | 5237.923 51 | 5304.9322 | 1.26% | 5412.448 22 | 5577.034 79 |

| 18 | 5481.570 11 | 5551.3992 | 1.26% | 5660.668 47 | 5829.135 24 |

| 19 | 5718.171 18 | 5790.7056 | 1.25% | 5901.069 42 | 6072.609 25 |

| 20 | 5947.494 87 | 6022.6578 | 1.25% | 6133.372 45 | 6307.1254 |

| 21 | 6169.289 37 | 6246.9482 | 1.24% | 6357.2735 | 6532.320 18 |

| 22 | 6383.280 71 | 6463.314 | 1.24% | 6572.439 91 | 6747.793 77 |

| 23 | 6589.170 09 | 6671.3979 | 1.23% | 6778.506 85 | 6953.105 17 |

| 24 | 6786.6309 | 6870.8931 | 1.23% | 6975.073 19 | 7147.766 69 |

| 25 | 6975.305 31 | 7061.4199 | 1.22% | 7161.696 76 | 7331.237 74 |

| 26 | 7154.8003 | 7242.5556 | 1.21% | 7337.889 15 | 7502.918 41 |

| 27 | 7324.6835 | 7413.8431 | 1.20% | 7503.110 37 | 7662.143 36 |

| 28 | 7484.478 69 | 7574.8736 | 1.19% | 7656.763 83 | 7808.178 19 |

| 29 | 7633.661 69 | 7724.9165 | 1.18% | 7798.193 26 | 7940.221 94 |

| 30 | 7771.657 56 | 7863.7083 | 1.17% | 7926.684 64 | 8057.423 82 |

| 31 | 7897.841 32 | 7990.4162 | 1.16% | 8041.479 | 8158.929 24 |

| 32 | 8011.546 26 | 8104.473 | 1.15% | 8141.807 58 | 8243.978 73 |

| 33 | 8112.0875 | 8205.2323 | 1.14% | 8226.966 99 | 8312.078 42 |

| 34 | 8198.813 46 | 8292.0293 | 1.12% | 8296.4519 | 8363.196 |

| 35 | 8271.200 14 | 8364.3066 | 1.11% | 8350.124 34 | 8397.803 78 |

| 36 | 8328.9873 | 8421.6123 | 1.10% | 8388.2943 | 8417.116 82 |

| 37 | 8372.291 21 | 8463.9648 | 1.08% | 8411.709 99 | 8425.784 12 |

| 38 | 8401.576 36 | — | — | 8423.144 09 | — |

| 39 | 8418.019 85 | — | — | 8427.9374 | — |

| 40 | 8425.784 71 | — | — | — | — |

Table 5. The eigenenergies of vibrational levels for the ground state ${\rm{A}}{}^{{\rm{1}}}{\rm{\Sigma }}_{u}^{+}$ of Li2, relative to the bottom of the potential well (cm−1). |

| Vibrational levels | 7Li2 | Exp. of 7Li2 [11] | δ | Vibrational levels | 7Li2 | Exp. of 7Li2 [11] | δ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 127.568 43 | 127.2989 | 0.21% | 38 | 7428.303 59 | 7490.7088 | 0.83% |

| 1 | 376.880 56 | 379.5847 | 0.72% | 39 | 7552.610 13 | 7614.4744 | 0.81% |

| 2 | 623.157 98 | 628.7628 | 0.90% | 40 | 7672.434 98 | 7733.6054 | 0.79% |

| 3 | 866.395 79 | 874.8276 | 0.97% | 41 | 7787.653 52 | 7847.9802 | 0.77% |

| 4 | 1106.592 87 | 1117.7878 | 1.01% | 42 | 7898.142 05 | 7957.4828 | 0.75% |

| 5 | 1343.751 17 | 1357.6575 | 1.03% | 43 | 8003.781 36 | 8062.0058 | 0.72% |

| 6 | 1577.875 08 | 1594.4510 | 1.05% | 44 | 8104.461 43 | 8161.4558 | 0.70% |

| 7 | 1808.9708 | 1828.1805 | 1.06% | 45 | 8200.087 59 | 8255.7576 | 0.67% |

| 8 | 2037.045 63 | 2058.8553 | 1.07% | 46 | 8290.588 05 | 8344.8591 | 0.65% |

| 9 | 2262.107 44 | 2286.4820 | 1.08% | 47 | 8375.922 57 | 8428.7364 | 0.63% |

| 10 | 2484.163 98 | 2511.0647 | 1.08% | 48 | 8456.091 23 | 8507.398 | 0.60% |

| 11 | 2703.222 39 | 2732.6056 | 1.09% | 49 | 8531.141 77 | 8580.8882 | 0.58% |

| 12 | 2919.288 62 | 2951.1052 | 1.09% | 50 | 8601.173 15 | 8649.2902 | 0.56% |

| 13 | 3132.366 96 | 3166.5620 | 1.09% | 51 | 8666.3329 | 8712.7268 | 0.53% |

| 14 | 3342.459 56 | 3378.9730 | 1.09% | 52 | 8726.807 05 | 8771.36 | 0.51% |

| 15 | 3549.566 06 | 3588.3326 | 1.09% | 53 | 8782.803 46 | 8825.3883 | 0.48% |

| 16 | 3753.683 18 | 3794.6329 | 1.09% | 54 | 8834.532 03 | 8875.0421 | 0.46% |

| 17 | 3954.804 38 | 3997.8627 | 1.09% | 55 | 8882.186 98 | 8920.5765 | 0.43% |

| 18 | 4152.919 62 | 4198.0072 | 1.09% | 56 | 8925.936 07 | 8962.2626 | 0.41% |

| 19 | 4348.015 | 4395.0479 | 1.08% | 57 | 8965.920 77 | 9000.3768 | 0.38% |

| 20 | 4540.0726 | 4588.9617 | 1.08% | 58 | 9002.270 19 | 9035.1898 | 0.36% |

| 21 | 4729.070 25 | 4779.7214 | 1.07% | 59 | 9035.130 82 | 9066.9562 | 0.35% |

| 22 | 4914.9813 | 4967.2950 | 1.06% | 60 | 9064.709 43 | 9095.9063 | 0.34% |

| 23 | 5097.774 47 | 5151.6462 | 1.06% | 61 | 9091.312 89 | 9122.2439 | 0.34% |

| 24 | 5277.413 68 | 5332.7340 | 1.05% | 62 | 9115.350 98 | 9146.152 | 0.34% |

| 25 | 5453.857 92 | 5510.5127 | 1.04% | 63 | 9137.277 51 | — | — |

| 26 | 5627.061 02 | 5684.9326 | 1.03% | 64 | 9157.499 54 | — | — |

| 27 | 5796.971 59 | 5855.9387 | 1.02% | 65 | 9176.317 07 | — | — |

| 28 | 5963.532 81 | 6023.4718 | 1.01% | 66 | 9193.9154 | — | — |

| 29 | 6126.6823 | 6187.4674 | 0.99% | 67 | 9210.385 97 | — | — |

| 30 | 6286.352 01 | 6347.8558 | 0.98% | 68 | 9225.749 96 | — | — |

| 31 | 6442.468 | 6504.5615 | 0.96% | 69 | 9239.974 11 | — | — |

| 32 | 6594.950 43 | 6657.503 | 0.95% | 70 | 9252.977 34 | — | — |

| 33 | 6743.713 35 | 6806.5922 | 0.93% | 71 | 9264.627 73 | — | — |

| 34 | 6888.664 74 | 6951.7343 | 0.92% | 72 | 9274.726 95 | — | — |

| 35 | 7029.706 44 | 7092.828 | 0.90% | 73 | 9282.969 81 | — | — |

| 36 | 7166.734 29 | 7229.7651 | 0.88% | 74 | 9288.831 93 | — | — |

| 37 | 7299.6384 | 7362.4316 | 0.86% | — | — | — | — |

Table 6. Franck–Condon factors for the transition from the v′ = 0 of the ${\rm{X}}{}^{{\rm{1}}}{\rm{\Sigma }}_{g}^{+}$ state to the v″ = 0–74 of the ${\rm{A}}{}^{{\rm{1}}}{\rm{\Sigma }}_{u}^{+}$ state of 7Li2. |

| v″ | F–C factors | v″ | F–C factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.651 42 | 38 | 1.54E-10 |

| 1 | 0.600 29 | 39 | 7.65E-11 |

| 2 | 0.397 16 | 40 | 2.91E-11 |

| 3 | 0.214 89 | 41 | 2.24E-12 |

| 4 | 0.0988 | 42 | 1.16E-11 |

| 5 | 0.038 41 | 43 | 1.76E-11 |

| 6 | 0.0118 | 44 | 1.90E-11 |

| 7 | 0.002 01 | 45 | 1.81E-11 |

| 8 | 7.04E-04 | 46 | 1.61E-11 |

| 9 | 9.70E-04 | 47 | 1.38E-11 |

| 10 | 6.45E-04 | 48 | 1.15E-11 |

| 11 | 3.26E-04 | 49 | 9.41E-12 |

| 12 | 1.31E-04 | 50 | 7.63E-12 |

| 13 | 3.68E-05 | 51 | 6.15E-12 |

| 14 | 4.70E-07 | 52 | 4.94E-12 |

| 15 | 9.01E-06 | 53 | 3.97E-12 |

| 16 | 8.53E-06 | 54 | 3.18E-12 |

| 17 | 5.65E-06 | 55 | 2.56E-12 |

| 18 | 3.07E-06 | 56 | 2.06E-12 |

| 19 | 1.39E-06 | 57 | 1.66E-12 |

| 20 | 4.78E-07 | 58 | 1.34E-12 |

| 21 | 6.11E-08 | 59 | 1.09E-12 |

| 22 | 8.77E-08 | 60 | 8.90E-13 |

| 23 | 1.13E-07 | 61 | 7.30E-13 |

| 24 | 9.23E-08 | 62 | 6.10E-13 |

| 25 | 6.23E-08 | 63 | 5.10E-13 |

| 26 | 3.69E-08 | 64 | 4.30E-13 |

| 27 | 1.92E-08 | 65 | 3.70E-13 |

| 28 | 8.43E-09 | 66 | 3.10E-13 |

| 29 | 2.55E-09 | 67 | 2.70E-13 |

| 30 | 2.49E-10 | 68 | 2.30E-13 |

| 31 | 1.31E-09 | 69 | 1.90E-13 |

| 32 | 1.49E-09 | 70 | 1.60E-13 |

| 33 | 1.29E-09 | 71 | 1.40E-13 |

| 34 | 9.87E-10 | 72 | 1.10E-13 |

| 35 | 6.91E-10 | 73 | 9.00E-14 |

| 36 | 4.51E-10 | 74 | 6.00E-14 |

| 37 | 2.75E-10 | — | — |

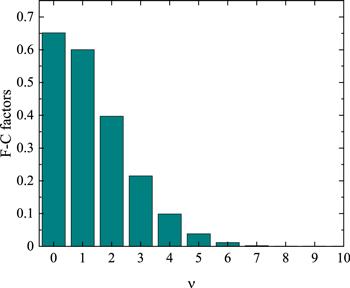

Figure 4. Franck–Condon factors for the transition from the v′ = 0 of the ${\rm{X}}{}^{{\rm{1}}}{\rm{\Sigma }}_{g}^{+}$ state to the v″ = 0–10 of the ${\rm{A}}{}^{{\rm{1}}}{\rm{\Sigma }}_{u}^{+}$ state of 7Li2. |