1. Introduction

2. Preliminaries

3. Quantum uncertainty relations of quantum coherence

For any $\alpha \in \left[\tfrac{1}{2},1\right)\cup (1,2]$, and qubit state equation (

Let $F(\theta ,\varphi )={r}_{X}+{r}_{Y}+{r}_{Z}$. Considering the partial derivation of $F(\theta ,\varphi )$ with respect to φ.

Using generalized binomial theorem, for any $l\in R$, one has

For $\alpha \in [1,2)$, since $\beta =\tfrac{1}{\alpha }-1\in \left[-\tfrac{1}{2},0\right)$, then $\left(\begin{array}{c}\beta \\ 2k+1\end{array}\right)=\beta (\beta -1)\cdots (\beta -2k)\leqslant 0$, in this case, f(x) is a polynomial function of monotone increasing. In the interval $\theta \in \left[0,\tfrac{\pi }{4}\right]$ and $\varphi \in \left[0,\tfrac{\pi }{4}\right]$, $u\geqslant v\geqslant 0$ implies $f(u)\geqslant f(v)$. Hence, $\tfrac{\partial F}{\partial \varphi }\geqslant 0$, i.e. $F(\theta ,\varphi )$ is an increasing function with respect to φ. These facts imply that $F(\theta ,\varphi )$ has a minimal value when $\varphi =0$. Under the circumstances,

For $\alpha \in \left[\tfrac{1}{2},1\right)$, since $\beta =\tfrac{1}{\alpha }-1\in (0,1]$, then $\left(\begin{array}{c}\beta \\ 2k+1\end{array}\right)=\beta (\beta -1)\cdots (\beta -2k)\geqslant 0$, therefore, f(x) is a polynomial function of monotone decreasing. In the interval $\theta \in \left[0,\tfrac{\pi }{4}\right]$ and $\varphi \in \left[0,\tfrac{\pi }{4}\right]$, $u\geqslant v\geqslant 0$ implies $f(u)\leqslant f(v)$. Hence, $\tfrac{\partial F(\theta ,\varphi )}{\partial \varphi }\leqslant 0$, i.e. $F(\theta ,\varphi )$ is a decreasing function with respect to φ. These facts imply that $F(\theta ,\varphi )$ has a maximum value when $\varphi =0$, and has a minimal value when $\varphi =\tfrac{\pi }{4}$. Similarly to the discussion in the case of $\alpha \in [1,2)$, we can find ${ \mathcal U }$ has a maximum value ${{ \mathcal U }}_{\max }$ when $\varphi =\tfrac{\pi }{4},\theta =\tfrac{1}{2}\arccos \tfrac{\sqrt{3}}{3}$, has a minimal value ${{ \mathcal U }}_{\min }$ when $\varphi =0,\theta =0,\tfrac{\pi }{4}$.□

For any $\alpha =\tfrac{1}{n+1}$, and qubit state equation (

The proof is analogous to theorem

For any $\alpha \in (\tfrac{1}{n+1},\tfrac{1}{n})$, and a qubit pure state $| \psi \rangle =\cos \theta | 0\rangle +{{\rm{e}}}^{{\rm{i}}\varphi }\sin \theta | 1\rangle $, where $n$ is a positive integer. With respect to the bases $X$, $Y$, and $Z$, the coherence sum satisfies

After a simple calculation, one has

Given a qubit state equation (

Let ${p}_{X}^{{\prime} }=| \langle x| \rho | x\rangle | =\lambda {p}_{X}+(1-\lambda )(1-{p}_{X})$, similarly, ${p}_{Y}^{{\prime} }=| \langle y| \rho | y\rangle | =\lambda {p}_{Y}+(1-\lambda )$$(1-{p}_{Y})$, and ${p}_{Z}^{{\prime} }\,=| \langle z| \rho | z\rangle | =\lambda {p}_{Z}+(1-\lambda )(1-{p}_{Z})$. Define $F(\theta ,\varphi )={ \mathcal U }(\rho )\,=H({p}_{X}^{{\prime} })+H({p}_{Y}^{{\prime} })$$+H({p}_{Z}^{{\prime} })-3H(\lambda ))$. Considering the partial derivation of $F(\theta ,\varphi )$ with respect to φ

In the case of $\varphi =\tfrac{\pi }{4}$, ${p}_{X}^{{\prime} }=\tfrac{1+{su}}{2}$, ${p}_{Y}^{{\prime} }={p}_{Z}^{{\prime} }=\tfrac{1+{sv}}{2}$, here $u=\cos 2\theta $, $v=\tfrac{\sqrt{2}}{2}\sin 2\theta $, $s=2\lambda -1$. $F\left(\theta ,\tfrac{\pi }{4}\right)=H\left(\tfrac{1+{su}}{2}\right)+2H\left(\tfrac{1+{sv}}{2}\right)-3H(\lambda )$. Since, ${u}^{2}+2{v}^{2}=1$, then $\tfrac{{\rm{d}}\ {u}}{{\rm{d}}\ {v}}=-\tfrac{2{v}}{{u}}$. Considering the derivation of $F\left(\theta ,\tfrac{\pi }{4}\right)$ with respect to v

Combined with $\tfrac{{\rm{d}}\ {v}}{{\rm{d}}\theta }=\cos 2\theta \geqslant 0$, one has $\tfrac{{\rm{d}}{F}\left(\theta ,\tfrac{\pi }{4}\right)}{{\rm{d}}\theta }\gt 0$ for $u\gt v$, and $\tfrac{{\rm{d}}{F}\left(\theta ,\tfrac{\pi }{4}\right)}{{\rm{d}}\theta }\lt 0$ for $u\gt v$. So $F\left(\theta ,\tfrac{\pi }{4}\right)$ has the maximum value $3H\left(\tfrac{1+(2\lambda -1)\tfrac{\sqrt{3}}{3}}{2}\right)-3H(\lambda )$ for u = v. In this situation, $\theta =\tfrac{1}{2}\arccos \tfrac{\sqrt{3}}{3}$.

4. The variation of the upper and lower bounds

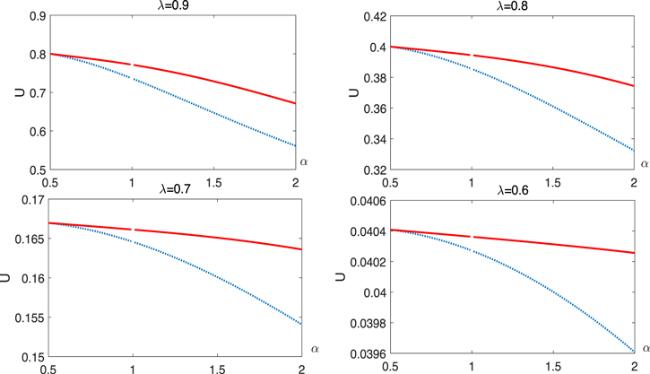

| • | We can find the differences between the upper and lower bounds increase with increase of the degree α. |

| • | We can find the differences between the upper and lower bounds increase with increase of the maximum eigenvalue of the state ρ. |

Figure 1. For $\alpha \in \left(\tfrac{1}{2},1\right)\cup (1,2]$, the comparison between lower and upper bounds, (a), (b), (c) and (d) represent, respectively, the cases of λ = 0.9, p = 0.8, p = 0.7 and p = 0.6. |

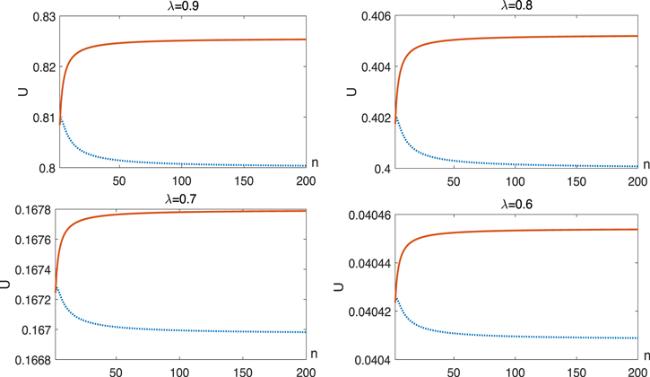

| • | We can find the differences between the upper and lower bounds increase with increase of the positive integer value n. |

| • | We can find the differences between the upper and lower bounds increase with increase of the maximum eigenvalue of the state ρ. |

Figure 2. For $\alpha =\tfrac{1}{n+1}$, where n is a positive integer, the comparison between lower and upper bounds, (a), (b), (c) and (d) represent, respectively, the cases of λ = 0.9, λ = 0.8, λ = 0.7 and λ = 0.6. |

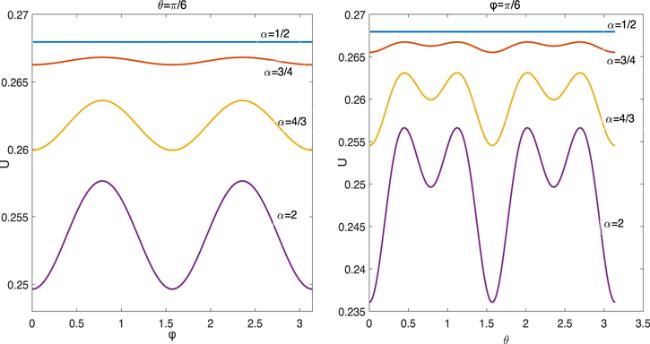

Figure 3. For the different degrees α, plots of ${ \mathcal U }(\rho )$ with respect to θ or φ. |