1. Introduction

2. Mathematical model

2.1. Formulation and basic equations

| 1. The Cartesian coordinate system $(x,\,y)\,$ is chosen as a frame of reference. | |

| 2. The single-phase model is utilized to describe the hybrid nanofluids while the Rosseland approximation model is taken for the radiative heat transport. | |

| 3. The hybrid nanofluids are composed of copper $\left({\rm{Cu}}\right)\,$ and aluminium oxide $\left({{\rm{Al}}}_{{\rm{2}}}{{\rm{O}}}_{{\rm{3}}}\right)\,$ nanoparticles with water as the base fluid. | |

| 4. The flat surface is being stretched or shrunk with velocity ${u}_{w}=\tfrac{ax}{1-\alpha t},$ where $a$ signifies the shrinking/stretching rate on the $x-$ axis. | |

| 5. The impacts of a variable magnetic field $B(t)=\tfrac{{B}_{o}}{\sqrt{1-\alpha t}}\,$ are taken in the vertical direction to the flow by neglecting the induced magnetic field. | |

| 6. Thermal stratification impacts are imposed on the flow fields for which the wall and ambient temperatures are taken to be variable, with the values ${T}_{w}={T}_{0}+\tfrac{{m}_{1}x}{1-\alpha t}$ and ${T}_{\infty }={T}_{0}+\tfrac{{m}_{2}x}{1-\alpha t}$, respectively. |

Figure 1. Flow geometry and coordinate system. |

Table 1. Thermo-physical characteristics of hybrid nanofluids and base fluid (see Khanafer et al [37], Oztop and Abu-Nada [38]). |

| Physical properties | Base fluid | Nanoparticles | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ${{\rm{H}}}_{{\rm{2}}}{\rm{O}}$ | ${\rm{Cu}}$ | ${{\rm{Al}}}_{{\rm{2}}}{{\rm{O}}}_{{\rm{3}}}$ | |

| $\rho \,\left(\mathrm{kg}/{{\rm{m}}}^{3}\right)$ | 997.1 | 8933 | 3970 |

| ${c}_{p}\,\left({\rm{J}}/(\mathrm{kg}\,{\rm{K}})\right)$ | 4179 | 385 | 765 |

| $k\,\left({\rm{W}}/({\rm{m}}\,{\rm{K}})\right)$ | 0.613 | 400 | 40 |

3. Numerical method

4. Computed results

4.1. Code validation

Table 2. Validation of the computed results $f^{\prime\prime} (0)$ with existing works for distinct values of $\lambda $ when $S=M=0={\phi }_{1}={\phi }_{2}={\alpha }_{1}=\beta .$ |

| Wang et al [39] | Mahapatra et al [40] | Ismail et al [36] | Present study | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| $\lambda $ | 1st sol. | 2nd sol. | 1st sol. | 2nd sol. | 1st sol. | 2nd sol. | 1st sol. | 2nd sol. |

| −0.25 | 1.402 24 | — | 1.402 242 | — | 1.402 240 7 | — | 1.402 240 189 17 | — |

| −1.00 | 1.328 82 | 0.0 | 1.328 819 | 0.0 | 1.328 816 8 | 0.0 | 1.328 817 063 98 | 0.0 |

| −1.15 | 1.082 23 | 0.116 702 | 1.082 232 | 0.116 702 | 1.082 231 1 | 0.116 672 4 | 1.082 231 659 85 | 0.116 702 098 941 |

| −1.20 | — | — | 0.932 470 | 0.233 648 | 0.932 473 3 | 0.233 628 4 | 0.932 473 336 374 | 0.233 649 713 559 |

Table 3. Comparison of results for upper and lower branch solution of $f^{\prime\prime} (0)$ for copper–water nanofluid $\left({\phi }_{1}=0\right)$ with variation in ${\phi }_{2}$ and $\lambda $ when $S=0=M=\,\,{\alpha }_{1}.$ |

| Bachok et al [41] | Present study | Bachok et al [41] | Present study | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| $\lambda $ | ${\phi }_{2}=0$ | ${\phi }_{2}=0$ | ${\phi }_{2}=0.1$ | ${\phi }_{2}=0.1$ | ||||

| 1st sol. | 2nd sol. | 1st sol. | 2nd sol. | 1st sol. | 2nd sol. | 1st sol. | 2nd sol. | |

| 2 | −1.887 307 | — | −1.887 306 042 99 | — | −2.217 106 | — | −2.217 104 650 18 | — |

| 1 | 0 | — | 0 | — | 0 | — | 0 | — |

| 0.5 | 0.713 295 | — | 0.713 294 691 244 | — | 0.837 940 | — | 0.837 939 760 888 | — |

| 0 | 1.232 588 | — | 1.232 587 137 01 | — | 1.447 977 | — | 1.447 976 378 46 | — |

| −0.5 | 1.495 670 | — | 1.495 669 414 89 | — | 1.757 032 | — | 1.757 031 241 15 | — |

| −1 | 1.328 817 | 0 | 1.328 817 063 98 | — | 1.561 022 | 0 | 1.561 022 618 78 | — |

| −1.15 | 1.082 231 | 0.116 702 | 1.082 231 659 85 | 0.116 702 098 941 | 1.271 347 | 0.137 095 | 1.271 347 637 5 | 0.137 095 345 211 |

| −1.2 | 0.932 473 | 0.233 650 | 0.932 473 336 374 | 0.233 649 713 559 | 1.095 419 | 0.274 479 | 1.095 422 329 9 | 0.274 478 788 987 |

| −1.2465 | 0.584 281 | 0.554 297 | 0.584 282 077 652 | 0.554 296 057 004 | 0.686 379 | 0.651 161 | 0.686 382 925 642 | 0.651 157 307 193 |

4.2. Discussion

Figure 2. Variation of $f^{\prime\prime} (0)\,$ with magnetic parameter $M\,$ against $\lambda .$ |

Figure 3. Variation of $-\theta ^{\prime} \left(0\right)\,$ with radiation parameter $R\,$ against $\lambda .$ |

Figure 4. Variation of $f^{\prime\prime} (0)\,$ with suction parameter $S\,$ against $\lambda .$ |

Figure 5. Variation of $-\theta ^{\prime} \left(0\right)\,$ with stratification parameter ${s}_{t}\,$ against $\lambda .$ |

Figure 6. Velocity fields $f^{\prime} \left(\eta \right)$ for distinct nanoparticle volume fraction ${\phi }_{1}.$ |

Figure 7. Temperature fields $\theta \left(\eta \right)\,$ for distinct nanoparticle volume fraction ${\phi }_{1}.$ |

Figure 8. Velocity fields $f^{\prime} \left(\eta \right)$ for distinct suction parameter $S\,.$ |

Figure 9. Temperature fields $\theta \left(\eta \right)\,$ for distinct nanoparticle volume fraction ${\phi }_{2}\,.$ |

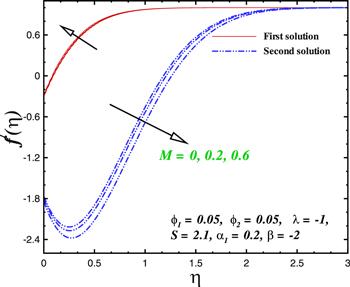

Figure 10. Velocity fields $f^{\prime} \left(\eta \right)$ for distinct magnetic parameter $M\,.$ |

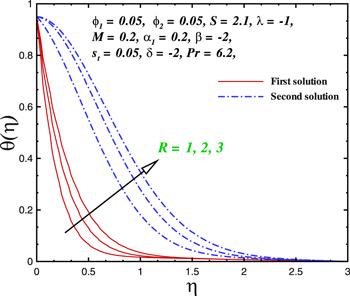

Figure 11. Temperature fields $\theta \left(\eta \right)\,$ for distinct radiation parameter $R\,.$ |

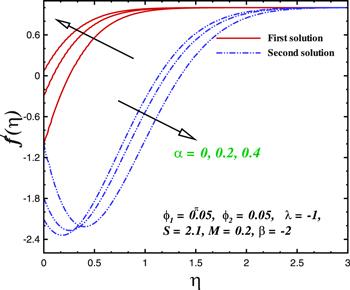

Figure 12. Velocity fields $f^{\prime} \left(\eta \right)$ for distinct velocity-slip parameter ${\alpha }_{1}.$ |

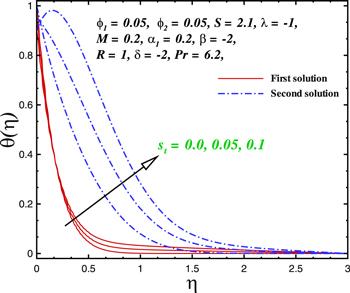

Figure 13. Temperature fields $\theta \left(\eta \right)\,$ for distinct stratification parameter ${s}_{t}.$ |

5. Main findings

| 1. As the suction parameter was increased, the existence domain of the dual solution was increased with higher critical values of the shrinking parameter. | |

| 2. A higher skin-friction coefficient was noted for larger values of the magnetic parameter in the upper branch. | |

| 3. At higher values of the stratification parameter, a substantial rise in fluid temperature was observed for both solutions. | |

| 4. Higher values of the radiation and thermal stratification parameters decreased the Nusselt number for both the upper and lower branch solutions. | |

| 5. A decreasing tendency was observed for velocity curves with increased values of the velocity-slip parameter in the case of the second solution. | |

| 6. The hybrid nanofluid temperature was significantly increased by a greater thermal radiation parameter in both solutions. |