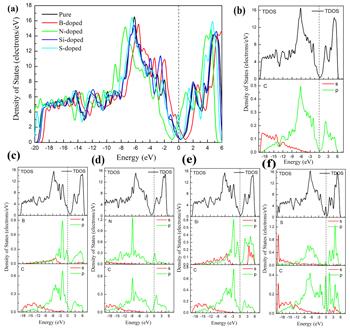

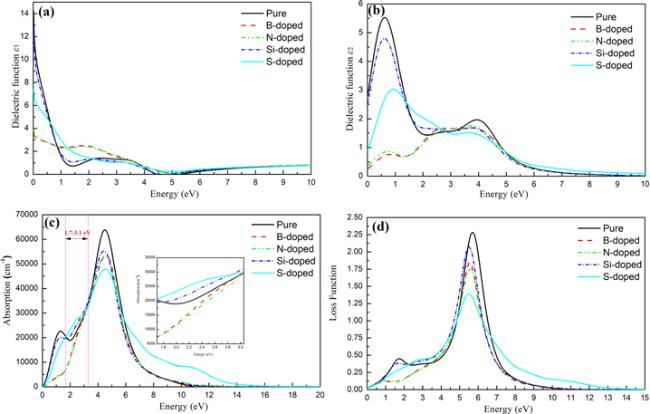

In order to better understand the mechanism of interaction between the doped atoms (B, N, Si, S) and graphene, we further calculated the band structure, density of states and charge density of the doped system. As shown in figure

3, we performed a systematic calculation of the band structure for unit cell of intrinsic graphene, the supercell of intrinsic graphene and B-, N-, Si- and S-doped graphene. From figures

3(a) and (b), we can see that the unit cell of intrinsic graphene and supercell of intrinsic graphene are all zero band gap semiconductor material. The results show that the expansion behavior of graphene does not have much effect on its band structure. It can be seen from figures

3(c) and (e) that the Fermi level has moved down due to the introduction of B atoms and Si atoms, which is because the B atom has only three valence electrons, one electron less than the C atom, and it is a typical p-type doping. It can be seen from figure

3(d) that the Fermi level moves up due to the presence of N atoms. This is because N atoms have five valence electrons, one more electron than C atoms, which is a typical n-type doping. We can seen from figure

3(e) that the introduction of an Si atom leads to the generation of impurity bands near the Fermi level. As shown in figure

4, we have systematically calculated the total density of states and atomic partial density of states of the perfect graphene and B-, N-, Si- and S-doped graphene. From figure

4(b), we can see that the perfect graphene exhibits a zero band gap semiconductor property, which is consistent with our previous calculation results of the band structure. We can observe from figures

4(c) and (e) that in the B- and Si-doped graphene systems, the total density of states is near the Fermi level, and the top of the valence band crosses the Fermi level, showing a p-type. The characteristics of doping are consistent with the calculation results of the band structure results. It can be seen from the partial density of states of the B atom and its neighboring C atom that B atoms and C atoms have a tendency to interact with each other in the valence band, as shown in figure

4(c). The sharp peaks appear, indicating that the B-doped system has formed a strong B-C covalent bond. It can be observed from figure

4(e) that the bottom part of the conduction band has crossed the Fermi level, making the doping system exhibit n-type doping characteristics, which is the result of the coupling effect between the p orbital of the N atom and the p orbital of the C atom. In figure

4(f), it can be seen that the total density of states has a sharp peak at the Fermi level, indicating the existence of an impurity band, which is consistent with the previous calculation of the band structure.