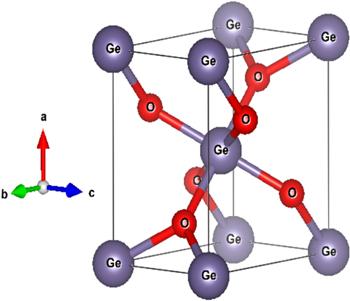

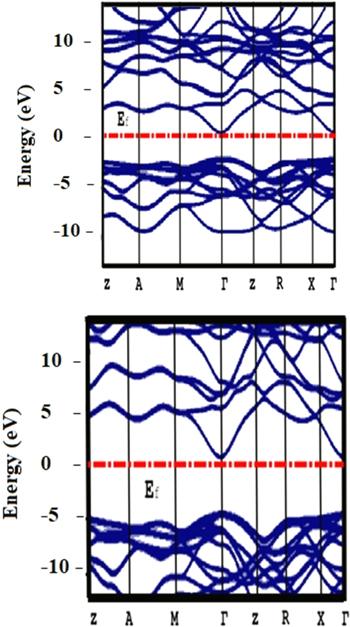

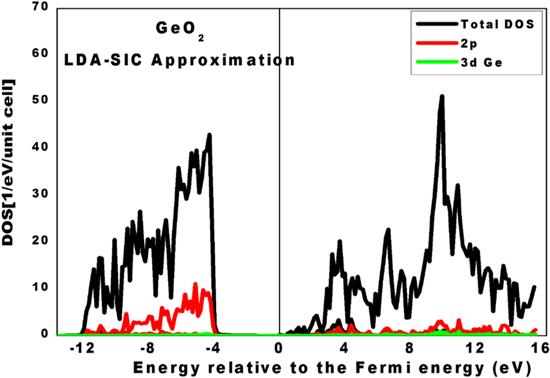

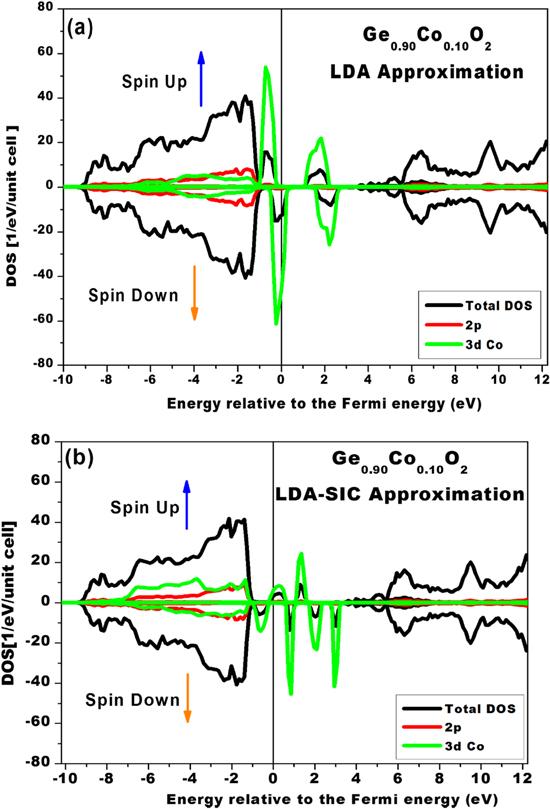

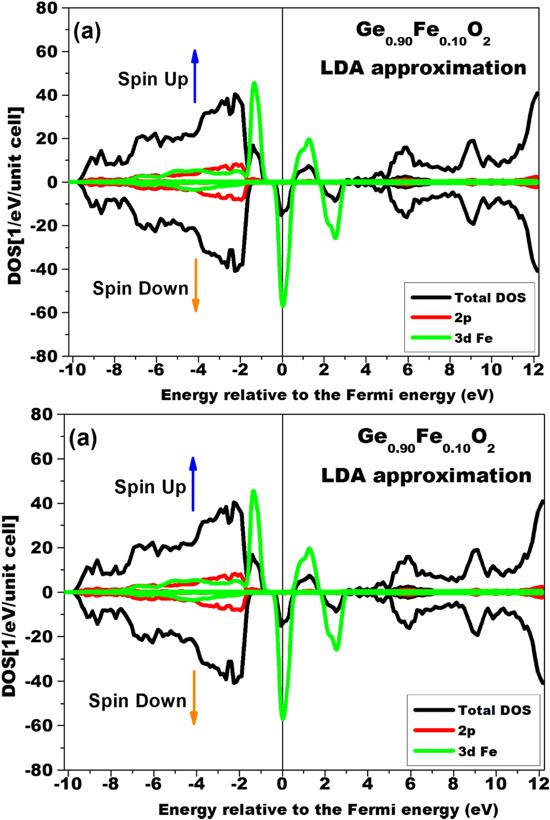

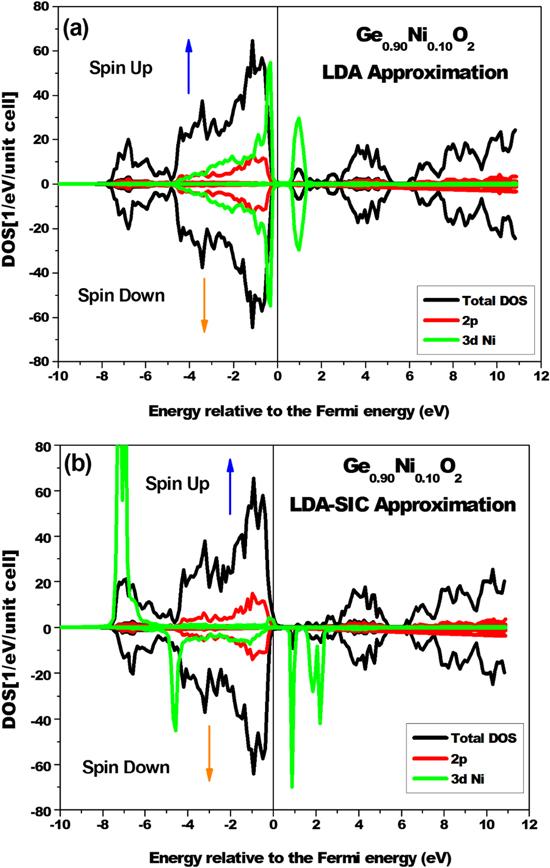

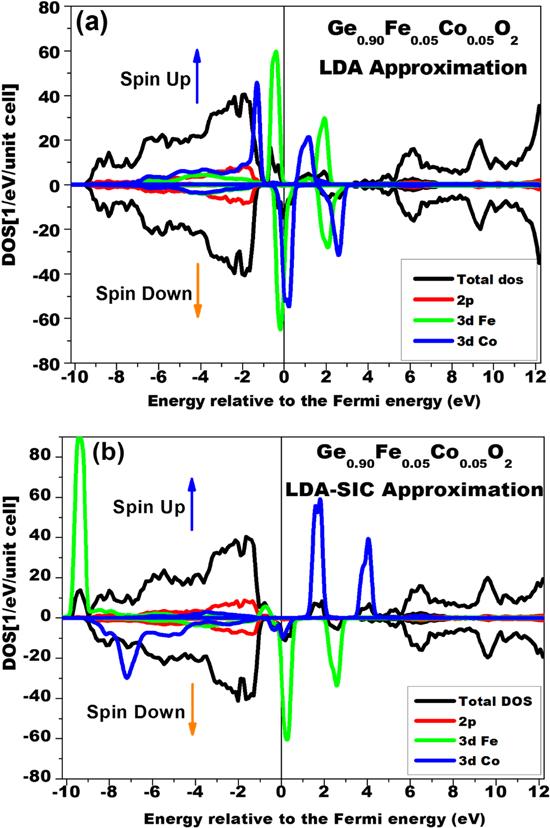

This paper describes density functional theory (DFT) calculations carried out for rutile germanium oxide, a semiconductor. Our objective is to calculate (using the local density approximation (LDA) and the LDA combined with the self-interaction correction approximation (LDA-SIC)) the band structure and the density of states (DOS) with the objective of predicting the spin polarization near the Fermi level and the critical temperature of this material. These calculations will demonstrate whether a GeO

2 semiconductor with a rutile crystallographic structure may or may not be considered to be a DMS material. It should be underlined that even if the results are encouraging, the critical temperature should be greater than the ambient temperature for any eventual spintronic applications. The expected magnetic behavior in this semiconductor will be studied for rutile GeO

2 doped and then co-doped with Co and Fe transition metals. The doping concentration is set to 10%. In fact, this value remains smaller than the percolation threshold (16.66%) to avoid any phase transition of the system leading to crystallographic structure change. The choice of rutile germanium oxide semiconductor is due to its thermodynamic stability under ambient conditions in contrast with that of the

α-quartz GeO

2 polymorph [

21]. Several studies, both experimental and theoretical, have been devoted to the study of the optoelectronic and piezoelectric properties of GeO

2 compounds [

22–

28]. In addition, this material is known for its higher electron mobility and lower operating voltage [

29]. Some recent works have also shown that this compound is not only a great candidate for the lithium battery industry [

30], but also as a suspended material in fluids to improve their thermal performance [

31]. This modern type of heat transfer fluid (nanofluid) has received special attention thanks to its extraordinary physicochemical properties, which are found to be absent from conventional fluids [

32,

33]. However, to the best of our knowledge, no theoretical research into the half-metallicity of rutile GeO

2 has been reported in the research literature to date. In summary, to examine the possibility of a new material for the spintronic domain, we decided to carry out theoretical calculations for a rutile germanium oxide semiconductor. The results obtained provide valuable evidence of half-metallicity, and this research may contribute to the incorporation of rutile GeO

2 in future electronic devices.