1. Introduction

2. The background spacetime and free scalar field dynamics

Figure 1. Behavior of the effective potential V(r). (a) Behavior of the effective potential V (r) with l = 3, q = −0.4, −0.8, −1.0. (b) Behavior of the effective potential V (r) with q = −0.4, l = 1, 2, 3. |

3. The quasinormal modes

Table 1. The QNMs of the magnetic Gauss–Bonnet black hole with q = −0.2, −0.4, −0.6, −0.8, −1.0. |

| l | n | ω (q = −0.2) | ω (q = −0.4) | ω (q = −0.6) | ω (q = −0.8) | ω (q = −1.0) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 | 0.293048 − 0.0977316i | 0.294029 − 0.0975119i | 0.296807 − 0.0968192i | 0.302764 − 0.0949061i | 0.314077 − 0.0886489i |

| 1 | 0.264667 − 0.306401i | 0.266057 − 0.305544i | 0.269962 − 0.302871i | 0.278002 − 0.295519i | 0.287643 − 0.273043i | |

| | ||||||

| 2 | 0 | 0.483862 − 0.0967364i | 0.485422 − 0.0965197i | 0.489844 − 0.0958430i | 0.499358 − 0.0940295i | 0.518478 − 0.0882874i |

| 1 | 0.464106 − 0.295527i | 0.465941 − 0.294800i | 0.471125 − 0.292536i | 0.482099 − 0.286495i | 0.501498 − 0.267776i | |

| 2 | 0.430712 − 0.508500i | 0.433016 − 0.507043i | 0.439467 − 0.502535i | 0.452653 − 0.490619i | 0.469698 − 0.455538i | |

| | ||||||

| 3 | 0 | 0.675670 − 0.0964713i | 0.677826 − 0.0962576i | 0.683939 − 0.0955913i | 0.697129 − 0.0938113i | 0.724068 − 0.0881808i |

| 1 | 0.661004 − 0.292194i | 0.663362 − 0.291513i | 0.670037 − 0.289392i | 0.684316 − 0.283740i | 0.711697 − 0.266068i | |

| 2 | 0.633977 − 0.495836i | 0.636710 − 0.494567i | 0.644414 − 0.490631i | 0.660609 − 0.480204i | 0.687788 − 0.448399i | |

| 3 | 0.598885 − 0.711104i | 0.602106 − 0.709064i | 0.611124 − 0.702763i | 0.629563 − 0.686209i | 0.653874 − 0.637709i | |

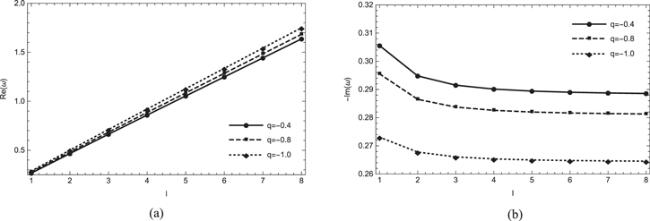

Figure 2. The quasinormal frequencies with n = 0. (a) The real part of quasinormal frequencies with n = 0, q = −0.4, −0.8, −1.0. (b) The imaginary part of quasinormal frequencies with n = 0, q = −0.4, −0.8, −1.0. |

Figure 3. The quasinormal frequencies with n = 1. (a) The real part of quasinormal frequencies with n = 1, q = −0.4, −0.8, −1.0. (b) The imaginary part of quasinormal frequencies with n = 1, q = −0.4, −0.8, −1.0. |

4. Gray-body factors and absorption cross-section

4.1. Gray-body factors

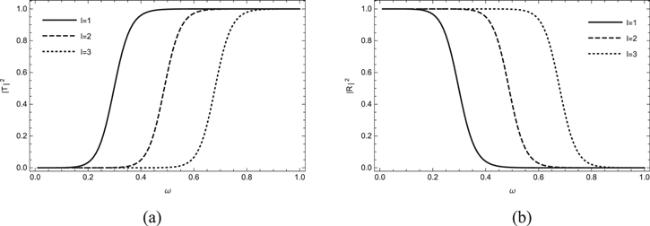

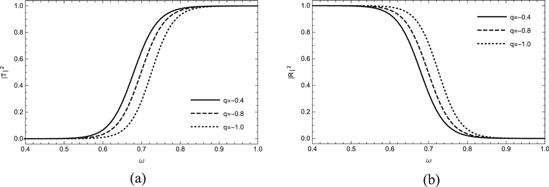

Figure 4. The dependence of ${\left|T(\omega )\right|}^{2}$ and ${\left|R(\omega )\right|}^{2}$ on ω for different spherical harmonic indices l with q = − 0.4. (a) The dependence of ∣T(ω)∣2 on ω for different spherical harmonic indices l. (b) The dependence of ∣R(ω)∣2 on ω for different spherical harmonic indices l. |

Figure 5. The dependence of ${\left|T(\omega )\right|}^{2}$ and ${\left|R(\omega )\right|}^{2}$ on ω for different magnetic charges q with l = 3. (a) The dependence of ∣T(ω)∣2 on ω for different magnetic charges q. (b) The dependence of ∣R(ω)∣2 on ω for different magnetic charges q. |

4.2. Absorption cross section

4.2.1. Numerical computations

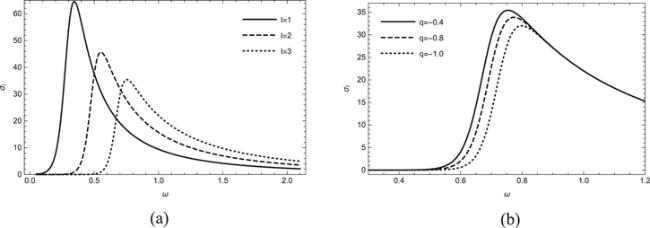

Figure 6. The dependence of σl on ω for different magnetic charges q and spherical harmonic indices l. (a) The dependence of σl on ω for different spherical harmonic indices l with q = −0.4. (b) The dependence of σl on ω for different magnetic charges q with l = 3. |

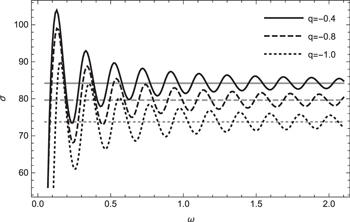

Figure 7. The dependence of σ on ω (black lines) and the high-frequency limit of the absorption cross-section σhf (gray lines) for different magnetic charges q. |

4.2.2. High-frequency limit

5. Conclusions

| • | As the absolute value of the magnetic charge ∣q∣ increases, the real part of quasinormal frequency increases while its imaginary part decreases. The existence of magnetic charges will reduce the damping of scalar perturbation, but increase the frequency. |

| • | As the spherical harmonic index l increases, the real part of quasinormal frequency increases almost linearly, while its imaginary part decreases. Although the decay rate of scalar perturbation decreases, its variation range is very small. |

| • | As the overtone index n increases, the real part of quasinormal frequency decreases slightly while its imaginary part increases significantly. The higher the overtone index, the faster the decay. Therefore, the frequency of n = 0 after a certain time is dominant. |

| • | The transmission coefficient ${\left|T(\omega )\right|}^{2}$ decreases and hence reflection coefficient ${\left|R(\omega )\right|}^{2}$ increases with an increase in spherical harmonic index l or absolute value of the magnetic charge ∣q∣. The existence of a magnetic charge will reduce the gray-body factor, which makes the waves with the same frequency more difficult to be absorbed by the black hole. |

| • | In the low-frequency case, the transmission coefficient ${\left|T(\omega )\right|}^{2}\to 0$ and the reflection coefficient ${\left|R(\omega )\right|}^{2}\to 1$. In the high-frequency case, the situation is just the other way round. We have seen that higher frequency waves are more easily absorbed by black holes, and lower frequency waves are more easily scattered by black holes. |

| • | The peak of the partial absorption cross-sections moves to the right and becomes lower as l or the absolute value of q increases. In other words, the partial wave is more easily scattered by the black hole as the absolute value of the magnetic charge is larger. |

| • | The curve of the total absorption cross-section becomes lower as the absolute value of q increases, and its high-frequency limit is the area of black hole shadow. The overall absorption cross-section of the black hole vibrates near its optical geometric limit, that is, the shadow area of the black hole, and converges here. At the same time, the magnetic charge q will weaken the absorption capacity of the black hole. |