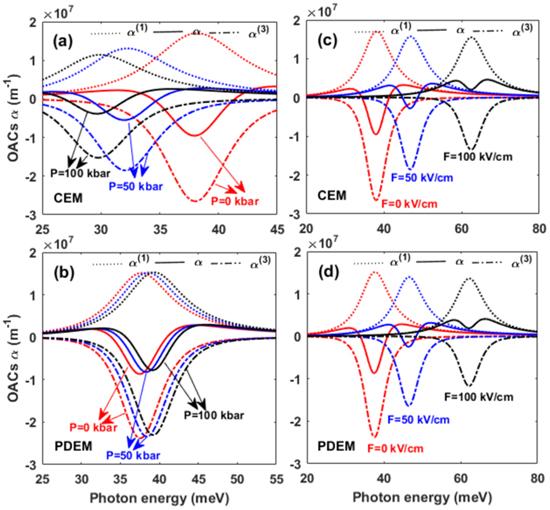

In figures

2(a) and (b), we present the variation of the first four energy levels

E0,

E1,

E2,

E3 and the energy difference

E10,

E20,

E30 are plotted as a function of the hydrostatic pressure

P with

F = 0 kV cm

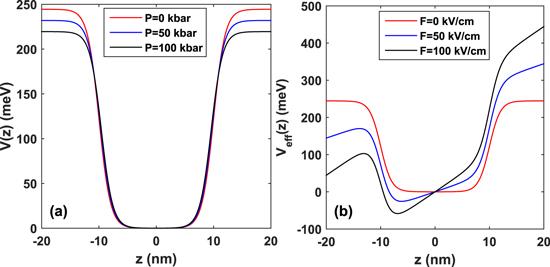

−1. It is seen from figure

2(a) that the conduction energy levels reduce monotonically for considering CEM as

P increases. Also, the energy level is more sensitive to the change of

P, especially for the high energy level. This may be a result of the weakening of depth confinement of the system due to an increase in

P. As seen from figure

1(a), the well depth decreases obviously as

P increases. The decrease of the well depth will directly result in the weakening of quantum confinement. More worthy of our attention is that the energy levels almost keep constant with the increase of

P for considering PDEM. It can be easily observed that the energy levels increase only a little bit as

P increases for the PDEM case. The change of energy levels with

P with PDEM is quite different from that with CEM. It is the result of a complex competition between kinetic energies and potential energies of the electron for the two cases when both the hydrostatic pressure and the position mass function are taken into account simultaneously. So the PDEM plays a major role in the study of the photoelectric effect. It can be understood quite easily in figure

2(b) that the energy difference

E10 between the first excited and ground states,

E20 between the second excited and ground states, and

E30 between the third excited and ground states decreases with increasing

P with CEM. However, the energy difference increases slowly with the increase of

P considering PDEM. In figures

2(c) and (d), we demonstrate the variation of the first four energy levels

E0,

E1,

E2,

E3 and the energy difference

E10,

E20,

E30 of Woods–Saxon QW as a function of applied electric field

F with

P = 0 kbar. It is observed from figure

2(c) that all energy levels almost slowly decrease as the

F increases. It is clear that the energy levels are dependent on the quantum confinement effect. By increasing

F, the quantum confinement of the electrons becomes weaker. As concluded from the results depicted in figure

1(b), it displays the variation of the confinement potential profile of Woods–Saxon QW for three different

F with

P = 0 kbar. We note that the asymmetry of Woods–Saxon QW increases as

F increases. Besides, it will give rise to the weakening of quantum confinement in the well width direction(see figure

2(c)). We notice that the change of the energy states shows similar behavior with the increase of

F for both cases CEM and PDEM. However, the influence of PDEM on the change of energy levels is more significant with increasing

F, especially for higher excited states. From figure

2(d), it can be noticed that the energy difference

E10 and

E20 increase with

F increasing, while we note that the energy difference

E30 shows a discontinuous change with the change of

F. It may be that the introduction of an electric field causes a more complex competition mechanism in the system.