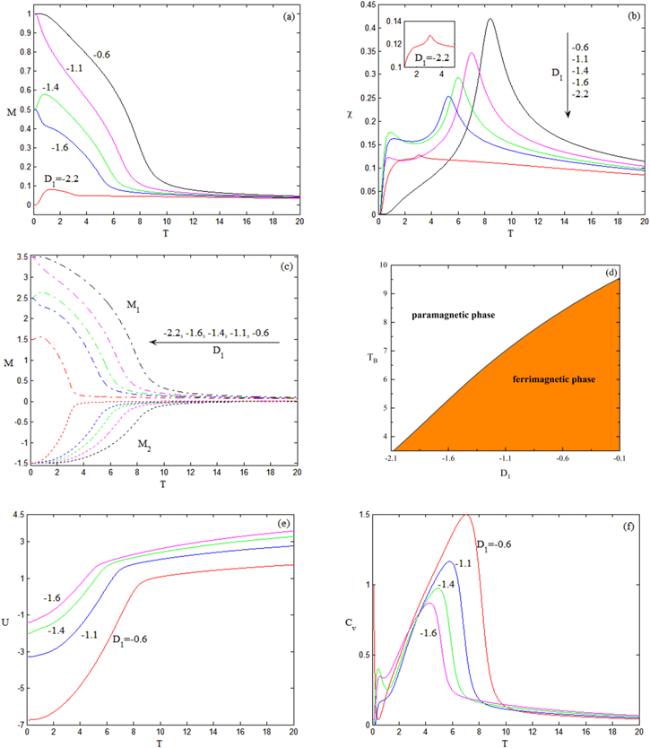

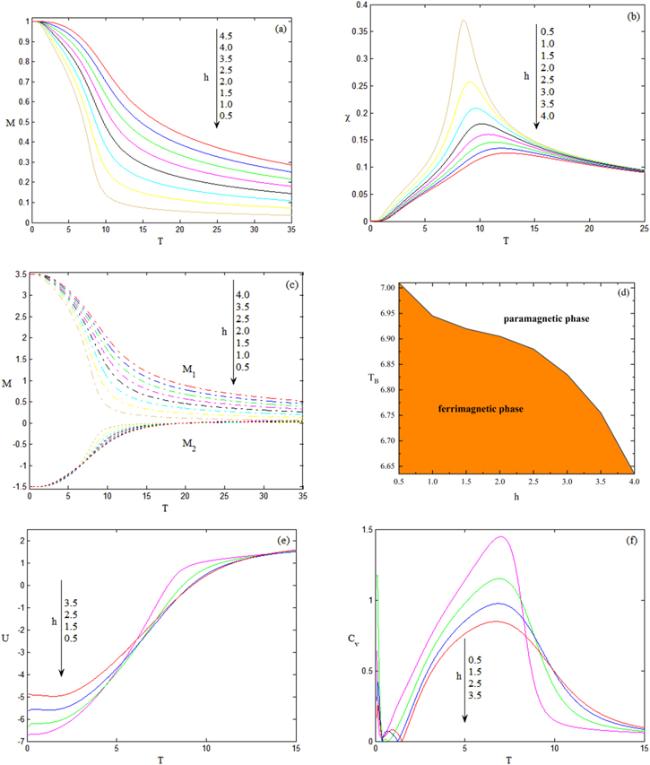

The influences of the anisotropy

D1 on the magnetic and thermodynamic properties of the bilayer nano-stanene-like structure are shown in figures

3(a)–(f). The typical parameters are

J = −1.5,

D2 = −2.0,

h = 0.4, and

N = 2. The temperature dependence of the total magnetization of the system is presented in figure

3(a), which shows two different behaviors. In the first type, the magnetization curve initially rises, drops, and finally becomes flat with the increase in temperature at

D1 = −1.4 and −2.2. In the other type, the magnetization curve increases with the decrease in temperature, and then becomes flat at

D1 = −0.6, −1.1, and −1.6. In the selected parameter range, the saturation magnetization (

Ms) has three different values,

Ms = 0, 0.5, and 1.0, when

D1 = −2.2, −1.6 (−1.4), and −1.1 (−0.6), respectively. To better understand the variation rule of the total magnetization

M of the system, figure

3(c) shows the variations of the magnetizations

M1 and

M2 of the sublattices of layers A and B of the system. With the change in

D1, the magnetization of

M1 changes significantly,

M1 = 1.5, 2.5, and 3.5, for

D1 = −2.2, −1.6 (−1.4), and −1.1 (−0.6), respectively.

M2 is constant, −1.5. The anisotropy

D1 mainly influences the magnetization of the A-layer sublattice. The temperature dependence of the susceptibility of the bilayer nano-stanene-like structure is shown in figure

3(b). A singular phenomenon at the blocking temperature is observed on the susceptibility curve. When

∣D1∣ increased, the blocking temperature at the singular position shifted toward a low temperature.

TB = 8.450, 7.005, 6.015, 5.285, and 3.07 for

∣D1∣ = 2.2, 1.6, 1.4, 1.1, and 0.6, respectively. The anisotropy

D1 dependence of the blocking temperature for the bilayer nano-stanene-like structure is shown in figure

3(d). The system blocking temperature decreases linearly with the increase in anisotropy

∣D1∣, which is consistent with the change in figure

3(b). When the temperature is higher than the blocking temperature, the system is in the paramagnetic phase (white region); otherwise, it is in the ferrimagnetic phase (yellow region). Similar results are also found in materials RKKY coupling [

48]. The temperature dependence of the internal energy (

U) for the bilayer nano-stanene-like structure is shown in figure

3(e). The system internal energy increases with the anisotropy

∣D1∣. However, the rate of increase gradually decreases. However, in the high-temperature region, the internal energy system almost directly increases with the increase in

∣D1∣, because, at low temperatures, the sublattices are slightly affected by the thermal disturbance energy and the influence of

D1 is dominant. However, with the increase in temperature, the thermal disturbance energy is dominant. The temperature dependence of the specific heat (

Cv) for the bilayer nano-stanene-like structure is shown in figure

3(f). The

Cv curves have a sharp peak at the blocking temperature for different values of

D1, which corresponds to the inflection point on the

U curve. The blocking temperature increases with the decrease in the anisotropy ∣

D1∣. In particular, the

Cv curves showed distinct peaks at low temperatures, because the

U curve showed an abnormal temperature dependence.