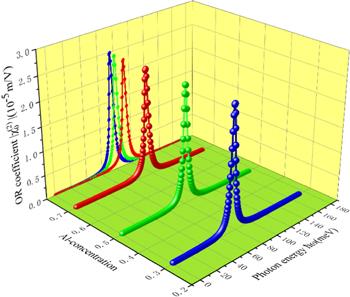

As shown in figure

3, take ${T}=300\,{\rm{K}},$ $\eta =0.5,$ ${V}_{0}=200\,{\rm{meV}},$ quantum dot radii are taken:

R = 4 nm, 5 nm, 6 nm, respectively. As can be seen from the figure: with the increase of the radius of the quantum dot, the ORC resonance peaks move towards the low-energy region, that is, ‘redshift'occurs. As shown in figure

1(a), the increase of quantum dot radius will lead to the decrease of energy level interval ${E}_{21},$ so the resonant peak positions of the ORC are redshifted. At the same time, we can see from the figure that the ORC peaks continue to rise, because the dipole transition matrix elements $\left|{M}_{12}^{2}{\delta }_{12}\right|$ increase with the quantum dot radius

R, and the wave function overlap becomes more and more obvious with the growing radius, which is the reason why this physical property appears.