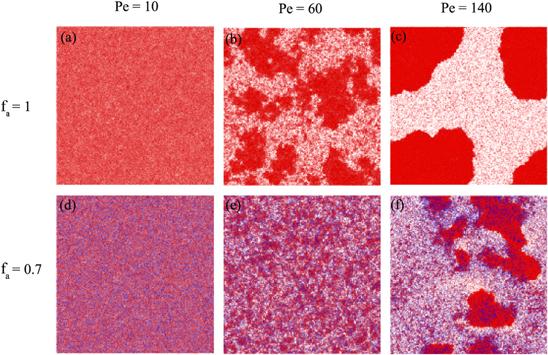

To directly observe the structures of the ABP systems, figure

1 shows snapshots for the different Péclet numbers at the same time in a purely active system (${f}_{{\rm{a}}}=1$) and the mixture containing $70 \% $ active particles (${f}_{{\rm{a}}}=0.7$) with the same fraction $\phi =0.7.$ In the case of lower activities ${Pe}=10,$ whether in purely active systems or mixtures, the studied systems are homogeneous and disordered in a liquid-like manner (see figures

1(a) and (d)). With increasing activities of ABPs (${Pe}=60$ in figures

1(b) and (e)), the particles form many small clusters that aggregate and disperse continually as time goes by. The larger the fractions of the active particles are, the larger the cluster size is. For the further larger

Pe, the clusters gather much more particles from their surrounding dilute regions and tend to close packing. The systems exhibit nucleation and the clusters grow. The particles that are not in the clusters are loosely distributed. As a result, the systems separate into dilute and dense phases. In other words, the systems exhibit the motility-induced phase separation (MIPS) as shown in figure

1(c). It should be noted that the passive particles suppress the activities of systems and prevent the occurrence of MIPS (see figure

1(f)). In a word, with increases in Péclet number and the fraction of active particles, the overall motility of the whole system has strengthened, and MIPS easily occurs.