Given that Λ might not be the ultimate truth, we are well motivated to construct alternative dark energy models. A simple and in some sense also minimal construction is to introduce a scalar degree of freedom. Because high-order derivative theories typically suffer from the Ostrogradsky instability [

36], it is often assumed that the Lagrangian density only depends on the scalar field value and its kinetic energy

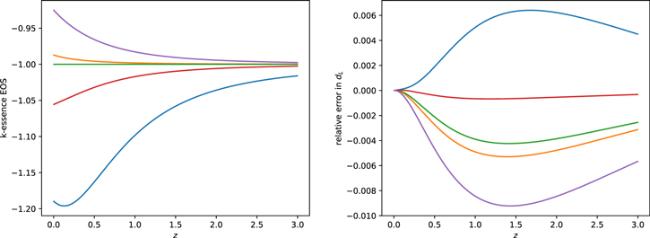

$X=\tfrac{1}{2}{\partial }_{\mu }\phi {\partial }^{\mu }\phi $. This class of dark energy models, often dubbed as k-essence models, allows a variety of cosmological solutions with rich phenomena [

37–

73]. In the early time when k-essence dark energy was first proposed, interests were more focused on using the so-called tracking solutions, where the field has attractor-like dynamics in the early Universe, to resolve the coincidence problem [

74–

77]. It was understood later that the tracking k-essence models are not very successful solutions to the coincidence problem, because they require additional fine-tuning and superluminal fluctuations [

78–

80]. Moreover, tracking models typically predict moderate deviation from Λ, which is more and more disfavored as the accuracy of observations improves [

7,

81]. Alternatively, one can consider the so-called thawing k-essence [

1,

82–

85], whose mass scale is close to or less than the current expansion rate of the Universe. In the thawing picture, the k-essence field is frozen by the large Hubble friction in the early Universe. Only at low redshift when the expansion rate drops below its mass scale, the field starts to roll. The lightness assumption (mass ≲

H0) of thawing k-essence naturally leads to non-clustering dark energy whose perturbations are suppressed on sub-horizon scales. There do exist, however, models of dark energy with noticeable sub-horizon perturbations [

86–

91]. In the present work we do not discuss clustering dark energy models, as they typically need to be treated in a one-by-one manner.