1. Introduction

2. Method and data

2.1. Simulation of the GW standard sirens

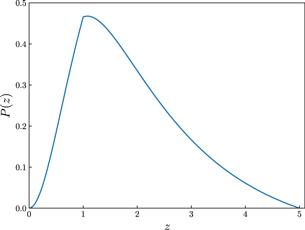

Figure 1. The redshift distribution of BNS mergers. |

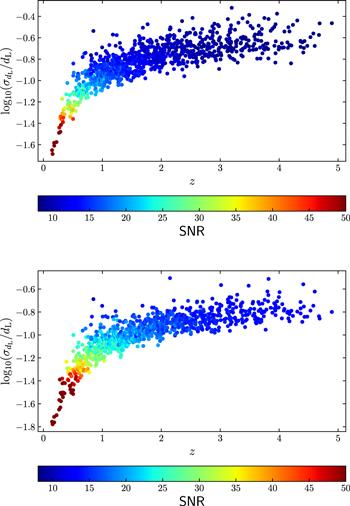

Figure 2. Distribution of ${\sigma }_{{d}_{{\rm{L}}}}/{d}_{{\rm{L}}}$ as a function of redshift. The color indicates the SNR of the simulated GW standard sirens. Upper: 1000 GW standard sirens from a 10-year observation of ET. Lower: 1000 GW standard sirens from a 10-year observation of CE. |

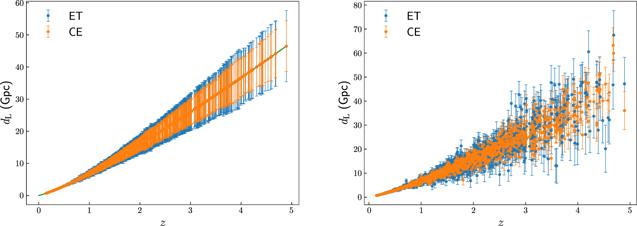

Figure 3. The simulated GW standard siren data points observed by ET and CE. The blue data points represent the 1000 standard sirens from the 10-year observation of ET and the orange data points represent the 1000 standard sirens from the 10-year observation of CE. Left: the standard siren data points without Gaussian randomness, where the central values of the luminosity distances are calculated by the fiducial cosmological model, and the solid green line represents the dL(z) curve predicted by the fiducial model. Right: the standard siren data points with Gaussian randomization, reflecting the fluctuations in measured values resulting from actual observations. |

2.2. Other cosmological observations

2.3. Method of constraining cosmological parameters

3. Results and discussion

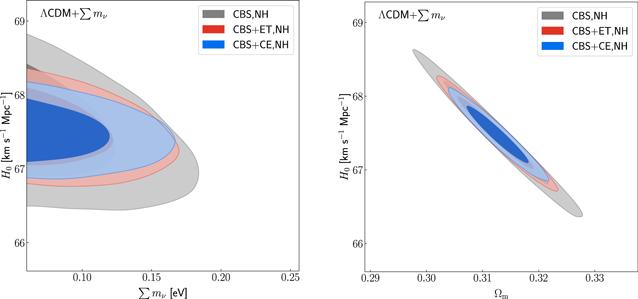

Figure 4. Two-dimensional marginalized contours (68.3% and 95.4% confidence level) in the ∑mν–H0 and Ωm–H0 planes using the CBS, CBS+ET, and CBS+CE data. Here CBS stands for CMB+BAO+SN. |

Table 1. The absolute and relative errors of cosmological parameters in the ΛCDM+∑mν model using the CBS, CBS+ET, and CBS+CE data. Note that H0 is in units of km s−1 Mpc−1 and CBS stands for CMB+BAO+SN. Here, 2σ upper limits on ∑mν are given. |

| ΛCDM | CMB+BAO+SN | CMB+BAO+SN+ET | CMB+BAO+SN+CE | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | NH | IH | DH | NH | IH | DH | NH | IH | DH |

| σ(Ωm) | 0.0062 | 0.0062 | 0.0064 | 0.0044 | 0.0044 | 0.0043 | 0.0036 | 0.0037 | 0.0036 |

| σ(H0) | 0.47 | 0.46 | 0.49 | 0.32 | 0.32 | 0.32 | 0.26 | 0.26 | 0.26 |

| ϵ(Ωm) | 1.98% | 1.97% | 2.07% | 1.41% | 1.40% | 1.39% | 1.15% | 1.18% | 1.16% |

| ϵ(H0) | 0.70% | 0.68% | 0.72% | 0.47% | 0.48% | 0.47% | 0.39% | 0.39% | 0.38% |

| ∑mν [eV] | <0.156 | <0.184 | <0.121 | <0.146 | <0.179 | <0.106 | <0.144 | <0.176 | <0.104 |

Table 2. The absolute and relative errors of cosmological parameters in the IΛCDM+∑mν model using the CBS, CBS+ET, and CBS+CE data. Note that H0 is in units of km s−1 Mpc−1 and CBS stands for CMB+BAO+SN. Here, 2σ upper limits on ∑mν are given. |

| IΛCDM | CMB+BAO+SN | CMB+BAO+SN+ET | CMB+BAO+SN+CE | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | NH | IH | DH | NH | IH | DH | NH | IH | DH |

| σ(Ωm) | 0.0081 | 0.0082 | 0.0081 | 0.0046 | 0.0045 | 0.0046 | 0.0037 | 0.0037 | 0.0037 |

| σ(H0) | 0.65 | 0.65 | 0.65 | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.36 | 0.27 | 0.27 | 0.27 |

| σ(β) | 0.0013 | 0.0013 | 0.0013 | 0.001 04 | 0.00103 | 0.00105 | 0.000 96 | 0.00096 | 0.00101 |

| ϵ(Ωm) | 2.62% | 2.65% | 2.65% | 1.49% | 1.46% | 1.50% | 1.20% | 1.20% | 1.20% |

| ϵ(H0) | 0.96% | 0.96% | 0.96% | 0.52% | 0.52% | 0.53% | 0.40% | 0.40% | 0.40% |

| ∑mν [eV] | <0.191 | <0.224 | <0.148 | <0.188 | <0.220 | <0.147 | <0.187 | <0.220 | <0.142 |

Table 3. The absolute and relative errors of cosmological parameters in the IwCDM+∑mν model using the CBS, CBS+ET, and CBS+CE data. Note that H0 is in units of km s−1 Mpc−1 and CBS stands for CMB+BAO+SN. Here, 2σ upper limits on ∑mν are given. |

| IwCDM | CMB+BAO+SN | CMB+BAO+SN+ET | CMB+BAO+SN+CE | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | NH | IH | DH | NH | IH | DH | NH | IH | DH |

| σ(Ωm) | 0.0079 | 0.0078 | 0.0079 | 0.0048 | 0.0048 | 0.0048 | 0.0039 | 0.0039 | 0.0039 |

| σ(H0) | 0.82 | 0.81 | 0.82 | 0.54 | 0.54 | 0.54 | 0.46 | 0.46 | 0.45 |

| σ(w) | 0.037 | 0.037 | 0.038 | 0.033 | 0.033 | 0.033 | 0.030 | 0.030 | 0.030 |

| σ(β) | 0.000 85 | 0.00087 | 0.00088 | 0.000 83 | 0.00080 | 0.00082 | 0.000 79 | 0.00079 | 0.00079 |

| ϵ(Ωm) | 2.56% | 2.52% | 2.57% | 1.56% | 1.55% | 1.55% | 1.27% | 1.26% | 1.27% |

| ϵ(H0) | 1.20% | 1.19% | 1.20% | 0.79% | 0.79% | 0.79% | 0.67% | 0.67% | 0.66% |

| ϵ(w) | 3.52% | 3.50% | 3.56% | 3.15% | 3.13% | 3.13% | 2.90% | 2.84% | 2.89% |

| ∑mν [eV] | <0.190 | <0.224 | <0.149 | <0.182 | <0.212 | <0.146 | <0.180 | <0.210 | <0.136 |

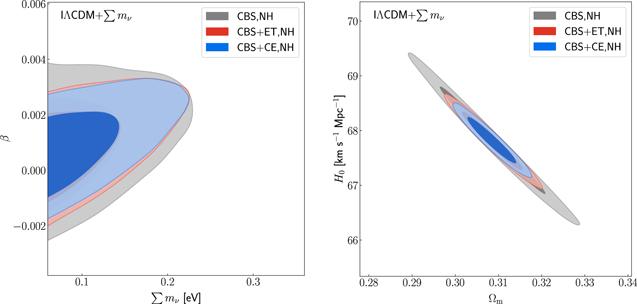

Figure 5. Two-dimensional marginalized contours (68.3% and 95.4% confidence level) in the ∑mν–β and Ωm–H0 planes using the CBS, CBS+ET, and CBS+CE data. Here CBS stands for CMB+BAO+SN. |

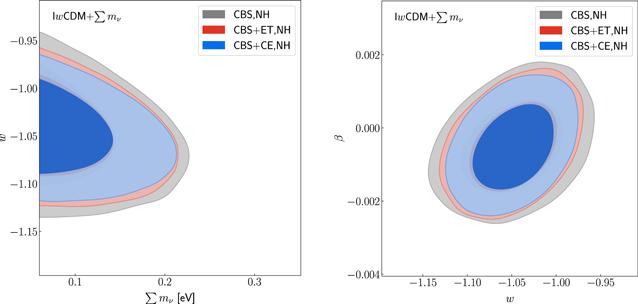

Figure 6. Two-dimensional marginalized contours (68.3% and 95.4% confidence level) in the ∑mν–w and w–β planes using the CBS, CBS+ET, and CBS+CE data. Here CBS stands for CMB+BAO+SN. |