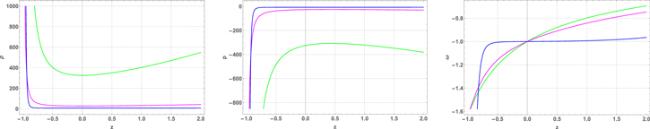

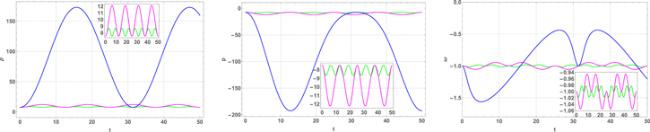

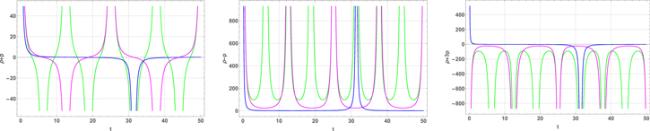

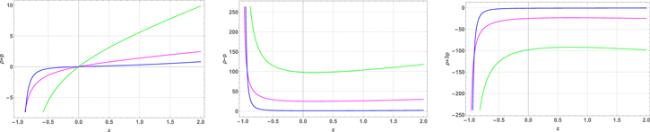

On the basis of Riemannian geometry and its extensions, three equivalent geometric descriptions of gravity can be achieved, the general theory of relativity (GR), introduced by Einstein, is the first one, formulated based on a very special type of connection, the symmetric and metric-compatible Levi-Civita connection. The other two are the teleparallel and symmetric teleparallel equivalent of GR. Here, we have focused on the modified

f(

Q) gravity or symmetric teleparallelism, where

Q is the non-metricity scalar. In this work, we have investigated the periodic cosmic evolution of

f(

Q) gravity models. More accurately, we have concentrated on the power law form i.e.

f(

Q) =

αQn+1 +

β and performed three cases for each different choice of

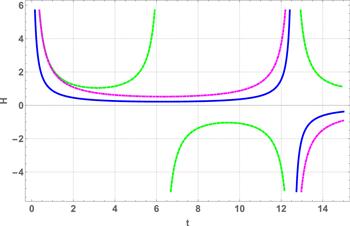

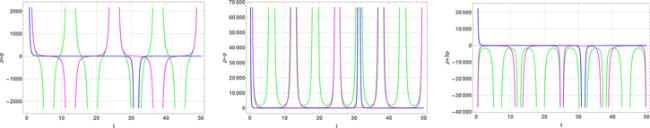

n = 0, 1, and −2. The system of field equations has been solved with the employment of a well-tested geometric parameter called PVDP. The corresponding scale parameter (a) and Hubble parameter (H) are obtained in [

29] and [

30] and graphically represented in figures

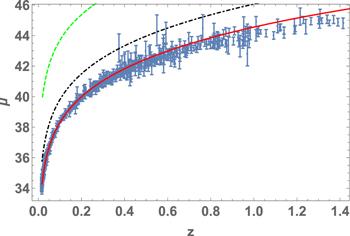

2 and

3. We have used Type Ia Supernovae observational datasets to check the validity of PVDP considered in our model. We have found the best fit of it with observational data as shown in figure

17. In the case of linear (

n = 0) and quadratic (

n = 1) cases, the big rip singularity has occurred at a finite time and it repeats periodically. In the third case (

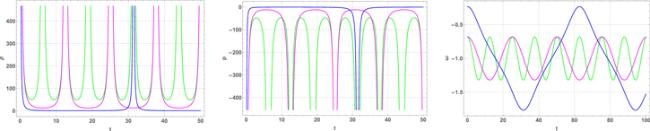

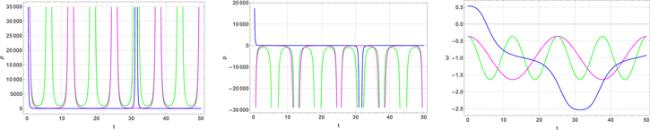

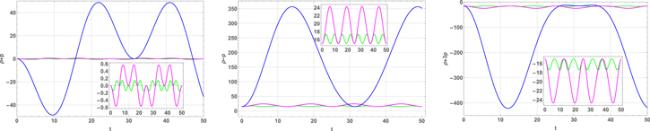

n = −2), the cyclic evolution has been evoked without any finite time singularity. Using the current observational values of the Hubble parameter and DP and their relationship, we have performed all physical analyses for various choices of parameter values. One can observe from figures

5 and

7 and

9 that the energy density is positive throughout the Universe whereas the pressure is always negative. In all the three considered cases our model coincides with ΛCDM as the EoS parameter

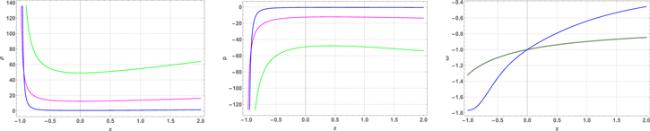

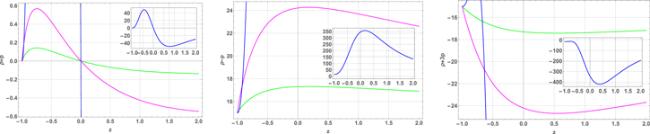

ω = −1 at

z = 0. All the ECs and dynamical properties have been described with the given choices of the parameter values. In general, the modification of GR evolution usually occurs at a lower curvature regime and higher curvature regime. The lower curvature regime leads to the late-time dark energy-dominated universe, while the higher curvature regime is applicable for the early universe. In that sense, the EoS parameters obtained in this work have eventually showed the evolutionary phase of the universe. For the first two cases with

n = 0 and

n = 1, the EoS parameter value varies between −2.5 <

ω < 0.5, which describes the phase transition universe from radiation to matter and then the dark energy era. However, in the third case with

n = −2 it lies between −1.5 <

ω < −0.5. It defines the phase of the universe completely dominated by dark energy. In addition, we have found here the ECs are consistent with the periodic evolution of model EoS parameter behavior from non-phantom to the phantom era in the linear and quadratic cases and the phantom to non-phantom era in the third case. This can be observed herewith that, the violation of ECs mostly occurred in the phantom phase. Also, the violation of ECs is leading to the existence of exotic matter fluid. That can be found in the literature [

37–

40] and references therein, one of the best examples is the traversable wormhole construction, in which the exotic matter fluid at the throat of a traversable wormhole allows time travel through it. It has been observed that a wormhole constructed in the framework of modified gravity theories has phantom fluid filled at its throat, which behaves as exotic to violate the ECs and allows the wormhole to be traversable. In such a scenario, we can consider the phantom era of the dark energy-dominated universe to behave as an exotic type or it has some exotic matter in it, which allows the ECs violation in certain phases. Henceforth, the present work contributes to the notion that the cyclic behavior of the late time universe can be achieved in

f(

Q) gravity formalism with or without singularity. Also, it can be more applicable to understanding the complete matter distribution of the universe in

f(

Q) gravity framework.