As mentioned, the radiation-pressure (or scattering) force originates from the photon scattered by the atomic dipole and is collinear to the direction of laser propagation. For

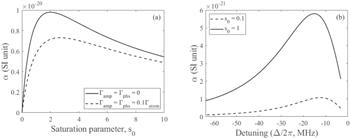

${\rm{\Delta }}\lt 0,$ this force acts as viscous drag and competes against the atomic velocity, therefore viscously hinders the atomic motion. Figure

2 illustrates the velocity-dependence of the scattering force on a two-level atom in 1D-OMs for three different saturation regimes. Figure

2(a) is plotted for the case

${{\rm{\Gamma }}}_{{\rm{amp}}}={{\rm{\Gamma }}}_{{\rm{phs}}}=0,$ while the other ones derived from a fluctuating laser beam. It can be observed that the scattering force is always positive (negative) for

$v\lt 0\,(\gt 0).$ The maxima for the scattering force occur at

$v\approx \pm \,{{\rm{\Gamma }}}_{{\rm{M}}}\sqrt{{s}_{0m}+1}/2k,$ and

${ {\mathcal F} }_{{\rm{scatt}}}^{\pm }$ decreases quickly for larger velocities. A comparison between the figures suggests that both amplitude and phase fluctuations reduce the magnitude of scattering force. With a fluctuating laser field, the scattering force is nearly linear with velocity for

${s}_{0}\leqslant 1.$ Also, it can be inferred that in a strong-field regime (

${s}_{0}\gg 1$), the phase fluctuation (related to the laser linewidth) is the dominant mechanism for damping of the atomic motion. In the weak-field limit, the damping rate, i.e. the slope of the curves near

$v=0,$ is highly sensitive to laser fluctuations. In contrast, this sensitivity reduces in the strong-field limit. Figures

2(c) and (d) show how the range of capture velocity is extended with the phase fluctuation. The capture velocity

${v}_{c}$ can be estimated as the velocity of an atom that is stopped by a force equal to half of the maximum scattering force. Referring to equation (

15), the range of capture velocity is

${v}_{c}\simeq {{\rm{\Gamma }}}_{{\rm{atom}}}/k$ for non-fluctuating laser beams, while this range changes to

${v}_{c}\simeq {{\rm{\Gamma }}}_{M}/k\,={({\gamma }_{1}{\gamma }_{3})}^{1/2}{{\rm{\Gamma }}}_{{\rm{atom}}}/k$ for the fluctuating laser fields. As it is expected, a wider range of capture velocities is attainable for the fluctuating laser fields. In other words, the ability to capture relatively hot atoms from the atomic beam increases by broadening the linewidth of the cooling fluctuating laser. It is worth mentioning that when

${{\rm{\Gamma }}}_{{\rm{phs}}}={{\rm{\Gamma }}}_{{\rm{atom}}},$ the capture velocity is twice its value for the non-fluctuating case. This doubled value for the capture velocity

$(\simeq 28\,{\rm{m}}\,{{\rm{s}}}^{-1})$ is still relatively small compared to the most probable typical velocities of a

${}^{88}{\rm{S}}{\rm{r}}$ thermal beam

$(\simeq 400\,{\rm{m}}\,{{\rm{s}}}^{-1}).$ It should be noted that due to the lack of restoring forces, the OMs do not trap neutral atoms that have been displaced from the center. This is why the Zeeman effect is used in an MOT to decelerate atoms before Doppler cooling [

35].