1. Introduction

2. Model and method

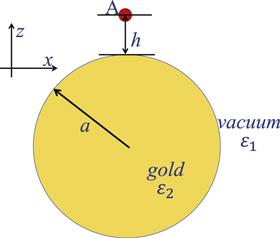

2.1. Model

Figure 1. Schematic diagrams. A QE is located around a gold nanosphere with radius a. The distance between the QE and the surface of the nanosphere is h. ϵ1 and ϵ2 are the permittivities for vacuum and metal, respectively. |

2.2. The resolvent operator technique

2.3. Effective Hamiltonian method

3. Results and discussion

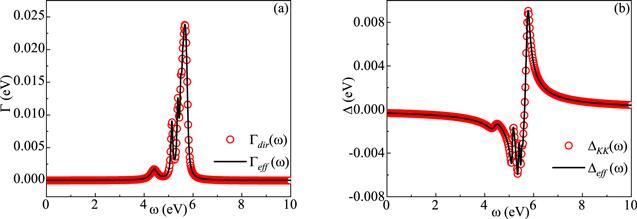

Figure 2. Spontaneous emission rate Γ(ω) and level shift Δ(ω) change with frequency (ω). In (a), Γ(ω) is a function of frequency (ω), the black solid line represents the result obtained from the exact solution of photon Green's function Γdir(ω), and the red dashed line is Γeff(ω) obtained by approximated pseudomodes. In (b), Δ(ω) is a function of frequency (ω), the black solid line is ΔKK(ω) obtained by subtracting the KK relationship, and the red dashed line is Δeff(ω) obtained by approximated pseudomodes. |

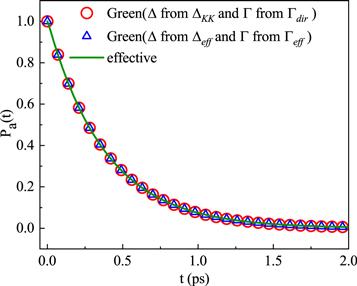

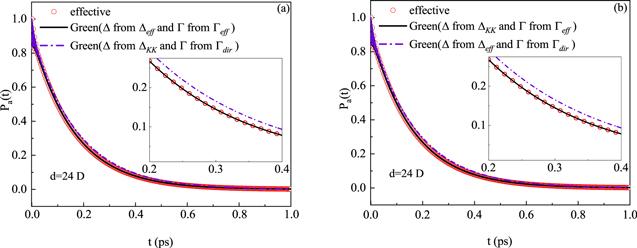

Figure 3. Evolution of the excited state population ${P}_{a}\left(t\right)={\left|{c}_{1}\left(t\right)\right|}^{2}$ with the variable t. The transition frequency ω0 = 5.8 eV, and the transition dipole moment d = 24 D. The results obtained by the resolvent operator method and the effective Hamiltonian method are compared, and the results agree well. The inset shows the results of a smaller time. In (a), the green solid line is the result obtained by the effective Hamiltonian method, and the red hollow circle is the result obtained by the rigorous resolvent operator method. The blue triangle is the result obtained by Γeff(ω) and Δeff(ω) is used in the resolvent operator method. In (b), the red hollow circle is the result obtained by ΔKK(ω) and Γeff(ω). The blue triangle is the result obtained by Δeff(ω) and Γdir(ω). The green solid line is the result obtained by the effective Hamiltonian method. |

Figure 4. Spontaneous emission rate Γ(ω) and level shift Δ(ω) change with frequency (ω), the distance between the QE and the surface of the nanosphere is h = 5 nm. In (a), Γ(ω) is a function of frequency (ω), the red hollow circle is Γdir(ω), and the black solid line is Γeff(ω). In (b), Δ(ω) is a function of frequency (ω), the red hollow circle is ΔKK(ω), and the black solid line line is Δeff(ω). |

Figure 5. Evolution of the excited state population ${P}_{a}\left(t\right)={\left|{c}_{1}\left(t\right)\right|}^{2}$ with the variable t. The transition frequency ω0 = 4.41 eV, and the transition dipole moment d = 24 D. The results obtained by the resolvent operator method and effective Hamiltonian method are compared. The green solid line is the result obtained by the effective Hamiltonian method, and the red hollow circle is the result obtained by the rigorous resolvent operator method. The blue triangle is the result obtained by Γeff(ω) and Δeff(ω) are used in the resolvent operator method. The results agree well. Here, the distance between the QE and the surface of the nanosphere is h = 5 nm. |

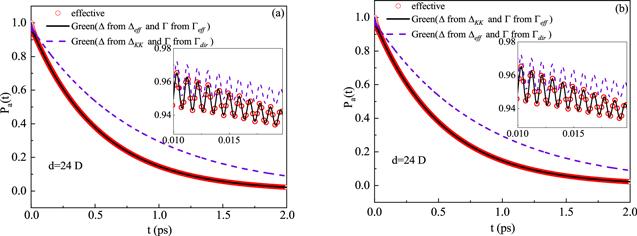

Figure 6. Evolution of the excited state population ${P}_{a}\left(t\right)={\left|{c}_{1}\left(t\right)\right|}^{2}$ with the variable t, here ω0 = 1.5 eV, and d = 24 D. The results obtained by the resolvent operator method and the effective Hamiltonian method are compared. In (a), the red hollow circle is the result obtained by the effective Hamiltonian method, and the black solid line is the result obtained by Γeff(ω) and Δeff(ω) are used in the resolvent operator method. The purple dashed line is the result obtained by ΔKK(ω) and Γdir(ω). In (b), the red hollow circle is the result obtained by the effective Hamiltonian method, the black solid line is the result obtained by ΔKK(ω) and Γeff(ω). The purple dashed line is the result obtained by Δeff(ω) and Γdir(ω). The inset shows the results of a shorter time. |

Figure 7. Evolution of the excited state population ${P}_{a}\left(t\right)={\left|{c}_{1}\left(t\right)\right|}^{2}$ with the variable t, here ω0 = 3.5 eV, and d = 24 D. The results obtained by the resolvent operator method and the effective Hamiltonian method are compared. In (a), the red hollow circle is the result obtained by the effective Hamiltonian method, and the black solid line is the result obtained by Γeff(ω) and Δeff(ω) is used in the resolvent operator method. The purple dashed line is the result obtained by ΔKK(ω) and Γdir(ω). In (b), the red hollow circle is the result obtained by the effective Hamiltonian method, the black solid line is the result obtained by ΔKK(ω) and Γeff(ω). The purple dashed line is the result obtained by Δeff(ω) and Γdir(ω). The inset shows the results of a shorter time. |

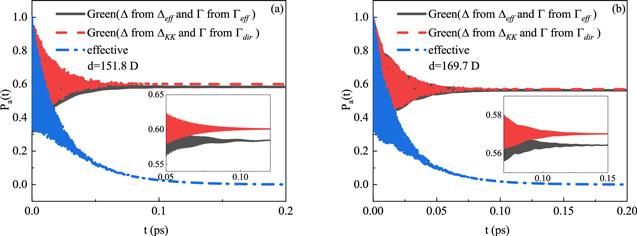

Figure 8. Evolution of the excited state population ${P}_{a}\left(t\right)={\left|{c}_{1}\left(t\right)\right|}^{2}$ with the variable t. When a bound state between QE and surface plasmon polaritons is formed, the results obtained by the resolvent operator method and the effective Hamiltonian method are compared. (a) shows the results for ${P}_{a}\left(t\right)$ with d = 151.8 D, the black solid line is the result obtained by Γeff(ω) and Δeff(ω) are used in the resolvent operator method, and the red dashed line is the result obtained by ΔKK(ω) and Γdir(ω). The blue dashed line is the result obtained by the effective Hamiltonian method. (b) shows the results for ${P}_{a}\left(t\right)$ with the transition dipole moment d = 169.7 D. |