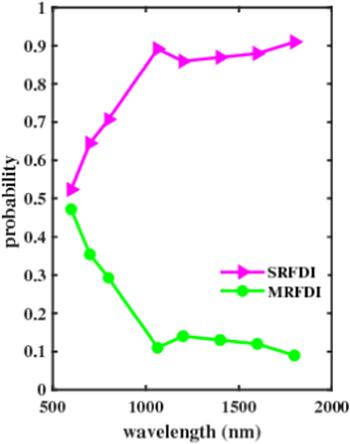

FDI of atoms and molecules has received a lot of attention in recent years. For example, because the second released electron has a dominant contribution to frustrated double ionization in the sequential regime, the photoelectron momentum distribution of FDI changes from a broad double-hump to a narrow single-hump structure with the increase of laser intensity in the Ar atomic has been observed by Larimian

et al [

26]. In a circularly polarized laser field, the FDI prefers low ionization potentials and short laser wavelengths, as studied by Kang

et al [

27], due to the fact that recollision plays an essential role in FDI not only for the NSDI regime but also for the SDI regime. Compared with an atomic target, the FDI of molecules is more complicated due to additional degrees of freedom, such as electron orbits, molecular alignment, and internuclear distance [

28]. For instance, in theoretical studies, Emmanouilidou

et al found that the probability of the recaptured electron in molecular FDI attaching to different nuclei can be explained by the initial velocity of tunneling electrons [

29]. They also demonstrated that the FDI of the double electron triatomic molecule D

3+ is significantly enhanced under the drive of counter-rotating two-color circular (CRTC) laser fields [

30]. The FDI of small molecules was also studied such as H

2 [

23,

31], D

2 [

32,

33], O

2 [

34], and CO [

35]. In these experimental studies, Manschwetus

et al reported evidence of electron recapture during strong-field fragmentation of H

2—explained by using a frustrated tunneling ionization model; McKenna

et al made a similar measurement of D

* in D

2 on Manschwetus's work, they examined the dependence of D

* generation on the pulse duration, intensity, ellipticity and angular distribution, it is also found that the features of D

* spectra are directly related to the D

+ spectra; Zhang

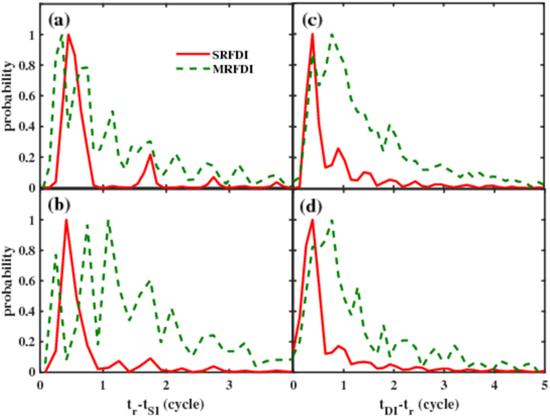

et al [

33] experimentally tracked the stepwise dynamics of the dissociative FDI of D

2 by monitoring the KER spectrum of nuclear fragments and the momentum distribution of freed electrons as a function of the time delay, their results show that ionized electrons are more easily recaptured in the second ionization step of producing dissociated FDI channel; In addition, Zhang

et al also studied the laser-induced dissociative frustrated multiple ionization of CO molecules, and found that the formation of C

* is more than that of O

*. Detailed studies have shown that molecular FDI can be identified by measuring the kinetic energies of the excited neutral fragments after dissociation, but what insight into the details of the electron emission dynamics underlying the molecular frustrated double ionization is still unclear.