In this work, our initial state is the ground state of ${{\rm{H}}}_{2}^{+}$, which is 1s

σg. Its relative strengths of the transitions to the

σu(

m = 0) and

πu (

m = ±1) channels play a commanding role in the determination of the MF-PMDs and MF-PADs by arbitrarily polarized attosecond pulses [

39]. For a linearly polarized laser, when the molecular axis is neither parallel nor perpendicular to the polarization vector, it takes the same general form as that for an elliptically polarized laser. In the case of

Rc = 2, the dipole transition to the channel

πu (perpendicular geometry) is far stronger than that to the channel

σu (parallel geometry) with

σ(⊥) = 528.5 kb and

σ(∥) = 38.95 kb, respectively. While for the case of

Rc = 4, they are

σ(∥) = 413.9 kb and

σ(⊥) = 284.8 kb, respectively [

39]. Consequently, at

Rc = 2, when the alignment angle is 0° (parallel geometry), only the transition to

σu has a contribution to the final MF-PMD and MF-PAD. When the alignment angle is slightly shifted, even only by 4°, the contribution from the

πu channel becomes more significant than that from the

σu channel. If the alignment angle is 45°, the electric amplitudes are equal in

x- and

y-directions, but the cross section of transition to

πu is much stronger than that to

σu, thus the final photoelectron distribution is

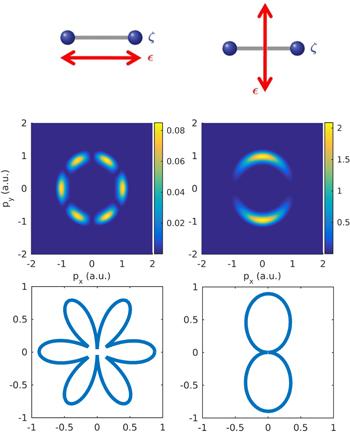

πu dominant and close to the results of perpendicular geometry as shown in figure

3. In the case of

Rc = 4, however, the transition cross sections to

σu and

πu are comparable. Actually, the one to

σ(∥) is even about 50% stronger than that to

σ(⊥). In this case, as the alignment angle shifts to 4°, it does not introduce much perpendicular geometry distribution to the final distribution and therefore, both the MF-PAD and MF-PMD do not change significantly. At the 45° alignment angle, where the

x- and

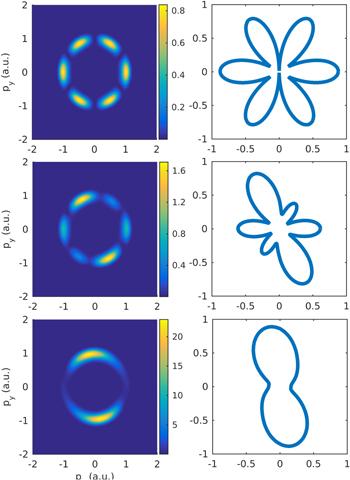

y-components of the electric field are equal, the parallel geometry distribution has a greater contribution to the final MF-PAD and MF-PMD than the perpendicular geometry distribution does, which is observed in the bottom row of figure

4.