1. Introduction

| i | (i) de Broglie [1], Einstein [2] and Planck [3]: moving bodies appear cooler, $T^{\prime} ={\gamma }^{-1}T;$ |

| ii | (ii) Eddington [4], Ott [5] and Arzelies [6]: moving bodies appear hotter, $T^{\prime} =\gamma T;$ |

| iii | (iii) Landsberg [7, 8]: temperature is a relativistic invariant, $T^{\prime} =T;$ |

| iv | (iv) Cavalleri, Salgarelli [9] and Newburgh [10]: no unique such transformation because thermodynamics are defined only in the rest frame. |

2. Elements of relativistic kinetic theory

3. Transformation rules in Minkowski spacetime

In relativistic physics, the spacetime dimension is often treated as an adjustable parameter. Whenever one draws some conclusion in relativistic physics, it is necessary to check whether the conclusion holds in generic spacetime dimensions or in some specific dimension. On the other hand, the behaviors of thermodynamic quantities are very sensitive to the dimension of the underlying space. Therefore, it makes sense to check whether the transformation rules uncovered in the present section are specific to (3 + 1)-dimensional Minkowski spacetime or whether they hold in arbitrary spacetime dimensions. In order to answer this question, it is necessary to extend the formulation to an arbitrary spacetime dimension $(d+1)$. In this regard, it is important to note that the fluid configuration is completely determined by $\left(\alpha ,{{ \mathcal B }}^{\mu },n,w,{ \mathcal T }\right)$, wherein, for a perfect fluid, α is a constant, ${{ \mathcal B }}^{\mu }$ is a Killing vector field, and, in Minkowskian backgrounds (see

The temperature, chemical potential, particle number density, entropy and enthalpy densities, and pressure of the perfect fluid are all defined as observer-dependent scalars (or scalar densities). Their transformation rules arise purely from the different choices of observers and have nothing to do with the coordinate choices. It is not surprising that at the same spacetime event, any two instantaneous observers can differ from each other at most by a local Lorentz boost (which is not a coordinate transformation of the spacetime). Such differences are independent of the choice of spacetime geometry. Therefore, it is highly expected that the same transformation rules should hold in other spacetimes, and we shall verify this expectation in Rindler spacetime in the next section.

4. Perfect Rindler fluid and the area law of entropy

5. Refined Saha equation

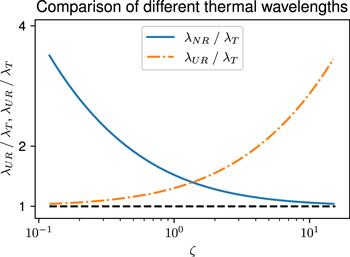

Figure 1. Comparison between λT and λNR, λUR. |