1. Introduction

2. Preliminaries: stabilizer states and magic states

Table 1. Qubit stabilizer states and the corresponding stabilizer generators, which stabilize the corresponding states and generate the corresponding maximal Abelian subgroups of ${{ \mathcal P }}_{2}$ stabilizing the corresponding states. For example, σx∣ + ⟩ = ∣ + ⟩, and σx generates the maximal Abelian subgroup {1, σx} stabilizing the state ∣ + ⟩. The three operators σx, σy and σz are the Pauli spin operators (matrices). |

| Stabilizer state | ∣ + ⟩ | ∣ − ⟩ | ∣ + i⟩ | ∣ − i⟩ | ∣0⟩ | ∣1⟩ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stabilizer generator | σx | −σx | σy | −σy | σz | −σz |

| a | (a) $1\leqslant M(\rho )\leqslant 1+(d-1)\sqrt{d\,+\,1}.$ |

| b | (b) M(ρ) is invariant under the Clifford operations in the sense that $M(V\rho {V}^{\dagger })=M(\rho ),\forall \ V\in {{ \mathcal C }}_{d}.$ |

| c | (c) M(ρ) is convex in ρ. |

| d | (d) Among all states (pure or mixed), M(ρ) achieves the minimal value 1 if and only if ρ = 1/d is the maximally mixed state. In view of this property, one may prefer to employ M0(ρ) = M(ρ) − 1 as a more appropriate quantifier of magic. However, we will not make this convention. |

| e | (e) Among pure states, M(∣ψ⟩⟨ψ∣) achieves the minimal value d if and only if ∣ψ⟩ is a stabilizer state. Consequently, all pure stabilizer states have the same value of magic (i.e. d). In particular, by the above properties, we have the following simple criterion for non-stabilizerness (magic states): if M(ρ) > d, then the state ρ is magic. It should be noticed that this is only a sufficient, but not necessary, condition for a state on ${{\mathbb{C}}}^{d}$ to be magic. |

3. Optimality of T-gate for generating magic-resource

3.1. Qubit T-gate

3.2. Qutrit T-gate

Table 2. Qutrit stabilizer states ∣φj⟩, j = 1, 2, ⋯,12, and the corresponding stabilizer generators, which stabilize the corresponding states and generate the corresponding stabilizer groups. For example, Z∣0⟩ = ∣0⟩, and Z generates the corresponding stabilizer group {1, Z, Z†}, which is a maximal Abelian subgroup of ${{ \mathcal P }}_{3}$ stabilizing the state ∣0⟩. Noting that XX† = ZZ† = 1, X3 = Z3 = 1, XZ = ω−1ZX, ω = e2πi/3. |

| Stabilizer state | Stabilizer generator |

|---|---|

| ∣φ1⟩ = ∣0⟩ | Z |

| ∣φ2⟩ = ∣1⟩ | ω−1Z |

| ∣φ3⟩ = ∣2⟩ | ωZ |

| $| {\phi }_{4}\rangle =\left(| 0\rangle +| 1\rangle +| 2\rangle \right)/\sqrt{3}$ | X |

| $| {\phi }_{5}\rangle =\left(| 0\rangle +{\omega }^{-1}| 1\rangle +\omega | 2\rangle \right)/\sqrt{3}$ | ω−1X |

| $| {\phi }_{6}\rangle =\left(| 0\rangle +\omega | 1\rangle +{\omega }^{-1}| 2\rangle \right)/\sqrt{3}$ | ωX |

| $| {\phi }_{7}\rangle =\left(| 0\rangle +| 1\rangle +\omega | 2\rangle \right)/\sqrt{3}$ | XZ |

| $| {\phi }_{8}\rangle =\left(\omega | 0\rangle +| 1\rangle +| 2\rangle \right)/\sqrt{3}$ | ω−1XZ |

| $| {\phi }_{9}\rangle =\left(| 0\rangle +\omega | 1\rangle +| 2\rangle \right)/\sqrt{3}$ | ωXZ |

| $| {\phi }_{10}\rangle =\left(| 0\rangle +| 1\rangle +{\omega }^{-1}| 2\rangle \right)/\sqrt{3}$ | XZ† |

| $| {\phi }_{11}\rangle =\left(| 0\rangle +{\omega }^{-1}| 1\rangle +| 2\rangle \right)/\sqrt{3}$ | ω−1XZ† |

| $| {\phi }_{12}\rangle =\left({\omega }^{-1}| 0\rangle +| 1\rangle +| 2\rangle \right)/\sqrt{3}$ | ωXZ† |

Table 3. Gates ${U}_{{\theta }_{1},{\theta }_{2}}=| 0\rangle \langle 0| +{{\rm{e}}}^{{\rm{i}}{\theta }_{1}}| 1\rangle \langle 1| +{{\rm{e}}}^{{\rm{i}}{\theta }_{2}}| 2\rangle \langle 2| $ with the maximal magic-resource-generating power, which include the qutrit T-gate T3 = U−2π/9,2π/9. All gates ${U}_{{\theta }_{1},{\theta }_{2}}$ with (θ1, θ2) in the following table are optimal for generating magic resource among the diagonal set of unitary gates, and yield the same value $1+2\sqrt{3}$ of maximal magic-resource-generating power. Actually, all these gates are Clifford equivalent to T3. |

| θ1 | $-\tfrac{2\pi }{9}$ | $-\tfrac{4\pi }{9}$ | $-\tfrac{8\pi }{9}$ | $-\tfrac{8\pi }{9}$ | $-\tfrac{8\pi }{9}$ | $-\tfrac{4\pi }{9}$ | $-\tfrac{2\pi }{9}$ | $\tfrac{2\pi }{9}$ | $\tfrac{4\pi }{9}$ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| θ2 | $\tfrac{2\pi }{9}$ | $\tfrac{4\pi }{9}$ | $\tfrac{8\pi }{9}$ | $-\tfrac{4\pi }{9}$ | $\tfrac{2\pi }{9}$ | $-\tfrac{2\pi }{9}$ | $\tfrac{8\pi }{9}$ | $\tfrac{4\pi }{9}$ | $\tfrac{8\pi }{9}$ |

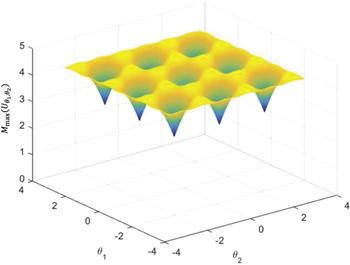

Figure 1. The graph of ${M}_{\max }({U}_{{\theta }_{1},{\theta }_{2}})$ on the domain θ1, θ2 ∈ [−π, π). We see that there are 18 pairs of (θ1, θ2) achieving the same maximal value $1+2\sqrt{3}\approx 4.4641.$ In the region −π ≤ θ1 ≤ θ2 < π, there are 9 pairs of (θ1, θ2), as listed in table 3, which achieve the maximal value. We also observe that ${M}_{\max }({U}_{{\theta }_{1},{\theta }_{2}})\geqslant 3$. |

| • | U−2π/9,2π/9 = T3, |

| • | U−4π/9,4π/9 = H2T3H2Z2, |

| • | U−8π/9,8π/9 = T3Z2, |

| • | U−8π/9,−4π/9 = T3Z2S, |

| • | U−8π/9,2π/9 = T3Z2S2, |

| • | U−4π/9,−2π/9 = H2T3H2Z2S2, |

| • | U−2π/9,8π/9 = T3S. |

| • | U2π/9,4π/9 = H2T3H2S, |

| • | U4π/9,8π/9 = T3ZS2. |

Table 4. Comparison between magic-resource-generating power for diagonal and general (non-diagonal) unitary gates in qubit and qutrit systems. Here ${{ \mathcal D }}_{d}$ is the set of diagonal unitary operators, which is a subgroup of the set ${{ \mathcal U }}_{d}$ of all unitary operators. |

| d | ${\max }_{U\in {{ \mathcal D }}_{d}}{M}_{\max }(U)={M}_{\max }({T}_{d})$ | ${\max }_{U\in {{ \mathcal U }}_{d}}{M}_{\max }(U)$ |

|---|---|---|

| 2 (qubit) | $1+\sqrt{2}$ | $1+\sqrt{3}$ |

| 3 (qutrit) | $1+2\sqrt{3}$ | 5 |