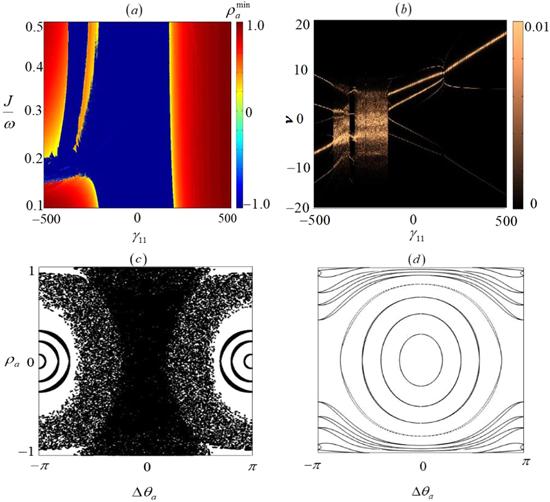

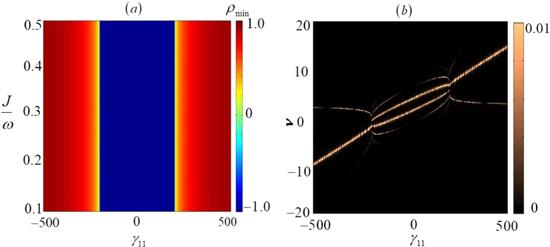

We consider the strong coupling regime (

K = 1.5) and numerically investigate the effect of atom–molecular coupling strength on atomic population balance. Starting from the same initial state

${\psi }_{\mathrm{int}}^{i}$, we show the diagram of

${\rho }_{a}^{\min }$ with the relative coupling

J/

ω and atomic interaction strength

γ11 in figure

3(a), which has changed a lot compared with the weak coupling case. Clearly, the symmetry of the parameter region about

γ11 = 0 is broken. For the case of interaction strength greater than zero (positive

γ11), the boundary of MQST transition is tilted and the transition happens at multiple critical parameter values

${\gamma }_{11}^{\mathrm{critical}}$. For case

γ11 < 0, irregular parameter regions of

${\rho }_{a}^{\min }\simeq -1$ and

${\rho }_{a}^{\min }\simeq 1$ appear. As the parameter

J/

ω increases from zero, there exist Rabi oscillation regions (

${\rho }_{a}^{\min }\simeq -1$) in the original MQST region. We find that these regions do not necessarily correspond to Rabi oscillations, but may also contain chaos. Next, we will prove the emergence of chaos by plotting the spectral density with the fixed

J/

ω = 0.25 as shown in figure

3(b). For positive

γ11, the spectral density contains only a finite number of frequencies, so the motion is periodic or quasi-periodic. The spectral density in the two-parameter regions of

γ11 < 0 contains a large number of frequencies which is an indicator of the underlying chaotic dynamics, and the two-parameter regions are called chaotic regions. To obtain a more complete characterization of chaos, we also plot the phase space diagrams on plane (

ρa, Δ

θa) in figure

3(c) with

γ11 = −350 and in figure

3(d) with

γ11 = 350 for fixed

J/

ω = 0.25 and

K = 1.5. The initial population differences are taken as ∣

ψ1(0)∣

2 − ∣

ψ2(0)∣

2 ∈ [−2/100, 2/100]. Clearly, figure

3(c) shows deformed tori coexisting with chaotic orbits, but for positive

γ11, these tori correspond to the quasi-periodic motion [figure

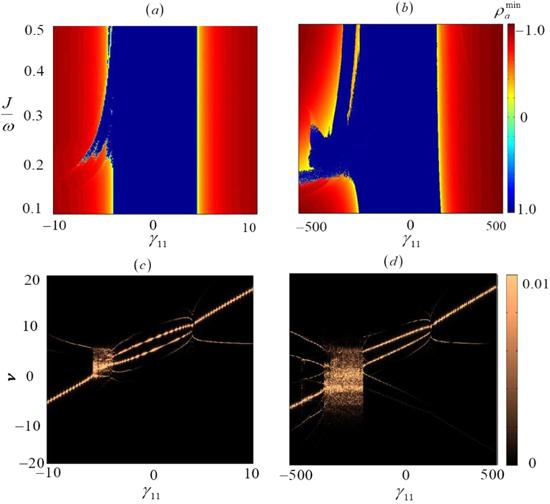

3(d)]. Taking parameters

K = 1.5 and

J/

ω = 0.25 and initial state

${\psi }_{\mathrm{int}}^{i}$ which are the same as those of figure

3(b), we choose interaction strength

γ11 = −350 localized in the chaotic region of figure

3(b), and show the time evolution of the population balance

ρa in figure

4(a) where the chaotic and aperiodic evolutions are observed. Figure

4(b) shows the periodic collapses and MQST for

γ11 = 350 localized in the regular region of figure

3(b).