Figures

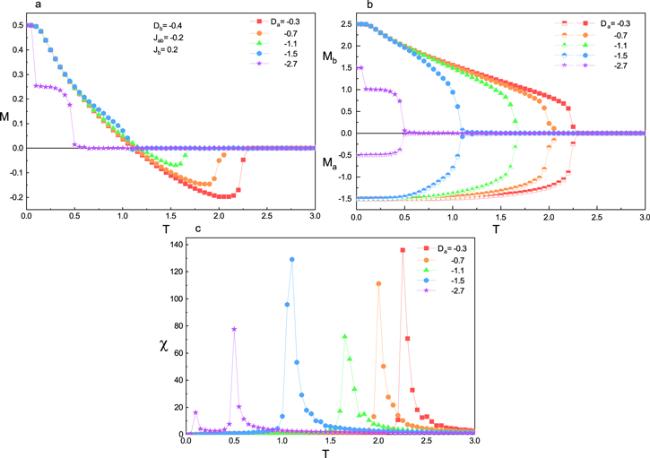

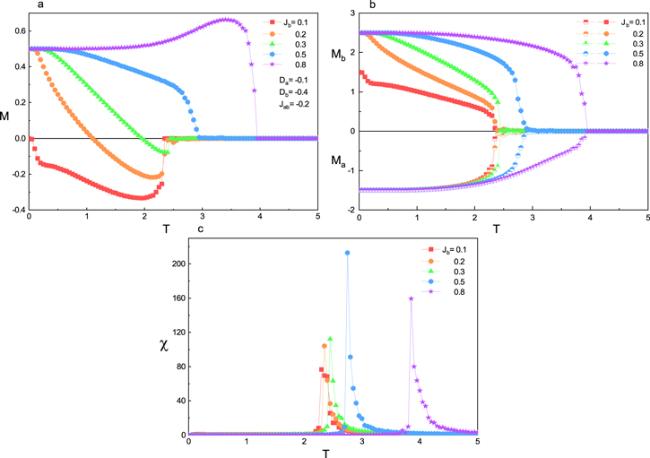

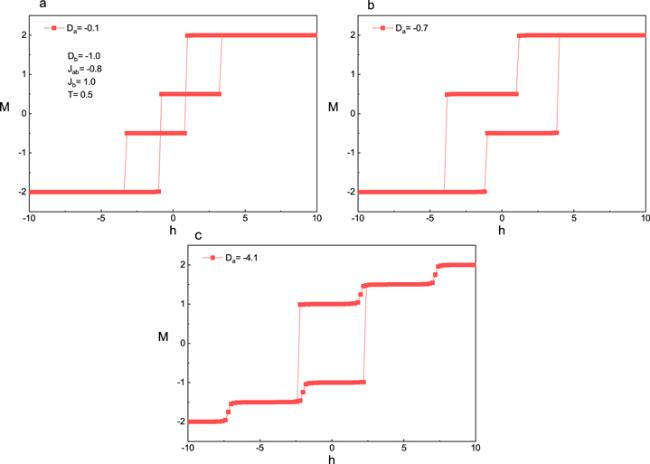

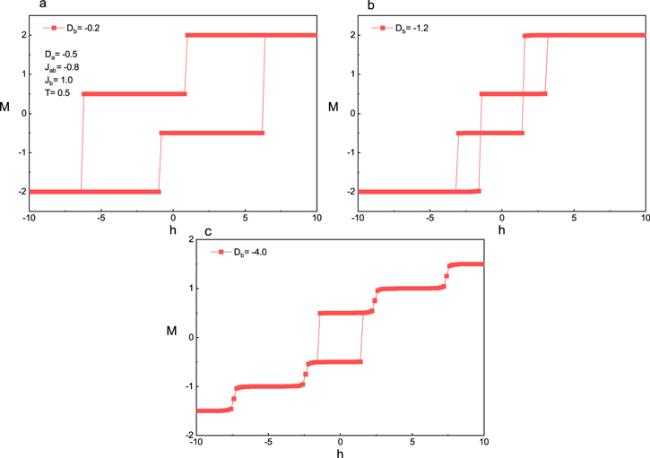

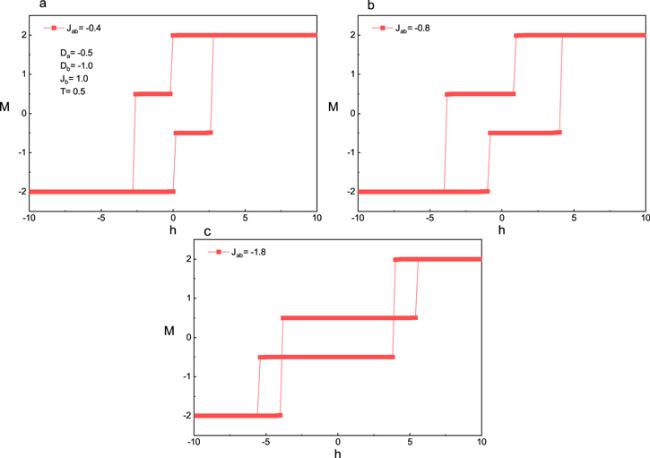

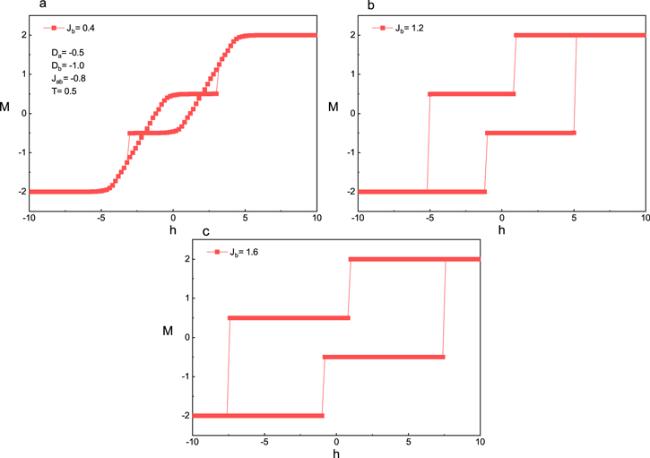

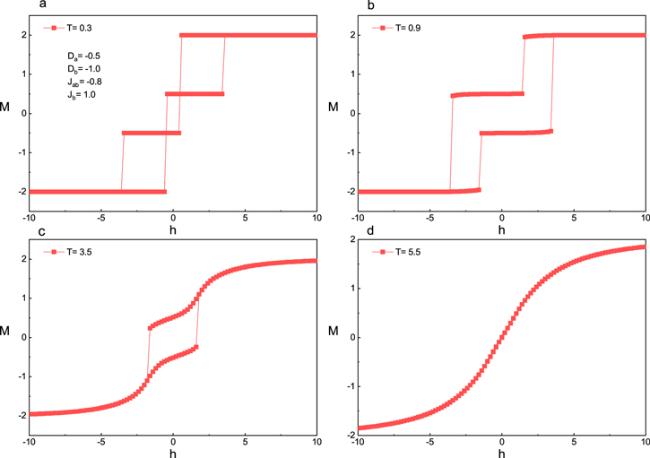

2(a)–(c) show the effect of

Da on the

M,

Ma,

Mb, and

χ with fixed

Db = −0.4,

Jab = −0.2, and

Jb = −0.2. The different behaviors of M curves can be obviously noticed in figure

2(a). When

Da is changed from −0.3 to −1.1, the

M curves first begin from the same saturation value

M = 0.5 to drop below zero and then approach the constant value (

M = 0) with

T increasing. It can be clearly noticed that there are two zero points in the

M curves. The temperature corresponding to

M = 0 in the low-temperature zone is the compensation temperature

Tcomp, which can be widely applied in the magnetic recording device [

36]. This type of

M curve pertains to the N-type curves predicted by

$N\acute{e}{el}$ theory [

37]. For the above compensation behavior, an explanation can be given. As

T increases, the

Ma and

Mb decrease at different speeds. Therefore, the

Ma and

Mb offset each other at the same temperature, at which total magnetization (

M) is zero, known as the compensation temperature (

Tcomp). In addition, as

Da decreases,

Tcomp moves slowly to the high-temperature zone. The stronger crystal field breaks the structural stability and makes the spins of sublattices flip more easily. In experiments, the compensation behavior has also been found in graphene-based film [

38]. It has been found that the possibility of designing a magnetically compensated graphene-based SAF/SFiM system is based on the discovery of the compensation temperature. It is worth noting that Ju. A. Mamalui

et al have found that the anisotropy in ferrite-garnet can influence the compensation temperature

Tcomp of the system [

39]. This is consistent with the conclusion found in figure

2(a). We can observe clearly in figure

2(b) that the magnetizations of sublattices (

Ma,

Mb) at

Tcomp are equal in value and opposite in direction. When

Da continues to be changed from −1.5 to −2.7, the P-type curves predicted by

$N\acute{e}{el}$ theory [

37] can be found. On one hand, the stronger

Da can help the spins of the sublattice flip from the high spin state to the low one, resulting in the appearance of more spin configurations. We can also notice clearly in figure

2(b) that when

Da = −2.7,

Ma is changed from −1.5 to −0.5, and

Mb is changed from 2.5 to 1.5. In fact, each kind of sublattice has its own crystal field, which affects the corresponding magnetization of the sublattice directly. For example, in figure

2(b), the crystal field of sublattice a

Da can directly influence its magnetization

Ma and correspondingly the saturation values of

Ma are also changed. However, due to the existence of the exchange coupling

Jab between the sublattices a and b,

Mb is also affected by the change of

Da. As one can notice, the

Mb also exhibits an additional small saturation value

Mb = 1.5 for the relatively strong anisotropy

Da = −2.7. Besides, the profile of the

Mb curve is not only directly determined by the crystal field

Db, but also by the various exchange couplings

Jab,

Jb, and temperature. On the other hand, with the increase of temperature, the thermal disturbance can release the frustrated spin states, resulting in a significant reduction in the

M with

T increasing. Similarly, the same spin frustration behavior with the maximum of magnetic moment can be discovered in the experimental investigations of the graphene-layered structures [

40,

41]. Namely, a maximum in the magnetization curve at low temperatures can be observed, which corresponds to the coexistence of the spins with different spin states. The effects of

Da and

T on susceptibility

χ can be studied in figure

2(c). There is a peak in every

χ curve corresponding to the transition temperature

TC. It can be observed that the

TC moves to the low-temperature zone as

$\left|{D}_{a}\right|$ increases. This phenomenon is due to the competition between

Da and

T. The thermal disturbance caused by temperature increases the order of the system, while the negative increase of

Da can make the system more disordered. In addition, when

Da = −2.7, there are two peaks in the

χ curve. The existence of a peak at low temperature should be associated with the sudden drop in the

M curve with the same parameter in figure

2(a).