The cosmic microwave background waves are the remnants of the big bang at the beginning of the cosmological era. These waves are proof of the existence of this explosion and the theories based on it, such as the standard model and the inflation model, and it has a temperature distribution that is relatively uniform but has temperature anisotropies. These anisotropies are the result of density disturbances that happened during the big explosion. Most of our knowledge of the Universe is obtained from the anisotropy spectrum of cosmic background radiation and observations of large-scale structures. The mass of neutrinos affects the history of the expansion of the Universe and the growth of disturbances of different components of the cosmic flux, so the anisotropy spectrum of the cosmic background radiation and observations of large-scale structures are changing. Discovering the accelerated expansion of the Universe is also the main challenge of particle physics. Laboratory efforts in particle physics to measure the absolute mass of neutrinos have always faced great challenges, cosmological observations are more prone to measure the absolute mass of neutrinos. Since neutrinos with mass can play an important role in the large-scale structure in different periods of cosmic evolution, recently some studies using cosmic observations have tried to put constraints on the total neutrino mass and the effective number of relativistic degrees of freedom(

Neff). Also, the cosmic consequences of the interaction of dark energy and dark matter have been widely investigated. The subject of neutrino variable mass was first raised by Wetterich, Luca Amundella, and Beldi in the article [

1], and then they conducted interesting studies in this field, the results of which were published in the articles [

2,

3], and [

4]. Also, in the field of neutrinos with variable mass, Sajjadi, and Anari introduced a new model for the initiation of cosmic acceleration based on neutrinos with variable mass in the article [

5]. When massed neutrinos become non-relativistic, the Z2 symmetry is broken and the quintessence potential becomes positive from its initial value of zero. This positive potential behaves like a cosmological constant in the present age, accelerating the Universe during its slow-rolling stages of evolution. Unlike the ΛCDM model, dark energy in this model is dynamic, and the acceleration is not constant. Unlike some previous dark energy models with variable-mass neutrinos, they did not use adiabatic conditions that lead to instability. They have done other valuable works in the field of variable mass neutrinos [

5,

6] and recently in a paper [

7] they have presented a model that can predict the current acceleration of the Universe based on the entanglement of quintessence fields with non-relativistic neutrinos. To explain In this model, the dark energy density increases from zero and leads to the current cosmic acceleration. The most fundamental tool used to develop a fundamental theory beyond General relativity and the standard model of particle physics is the scalar field. Higgs, Inflaton, Burns-Dick, etc fields are examples of these scalar fields that play an important role in elementary particle physics models. Furthermore, the wide range of behavior encompassed by a scalar field provides further scope for exploring and understanding developing cosmological observations. Also, with a scalar field, modeling the behavior of other forms of energy is straightforward [

8]. An important motivation for considering quintessence models is the consideration of the ‘concordance problem’ the problem of explaining the initial conditions necessary to obtain a simultaneous approximation of the present-day matter density and quintessence. The only possible option is to fine-tune the energy density ratio to 1 part in 100 000 at the end of inflation. Symmetry arguments from particle physics are sometimes invoked to explain why the cosmological constant must be zero, [

9] but there is no known explanation for a positive, observable vacuum density. The quintessence field together with the cosmic neutrino background (CNB) has been widely discussed as an alternative mechanism to address the adaptation problem. Such models can be extended to capture initial inflation, i.e. to include the inflation phase. By choosing an alternative route, one can start from established inflation models and, coupled with CNB, obtain successful quintessence models [

10]. Because it can couple directly or gravitationally with other forms of energy, it is possible to explore interactions that would cause the quintessence component to naturally adjust to a density comparable to that of present-day matter. Indeed, recent research [

11] has introduced the concept of ‘tracker field’ models that have absorption-like solutions [

12,

13] that produce the current quintessence energy density without fine-tuning the initial conditions. Particle physics theories with dynamical symmetry breaking or non-perturbation effects have been found to create potentials with ultralight masses that support negative pressure and exhibit ‘tracker’ behavior [

14]. Many studies were conducted to find the origin of the current acceleration of the Universe. Indeed, much progress has been made since then, but understanding the fundamental physics in the acceleration of the Universe remains a question and one of the main challenges of modern physics. In the standard model of cosmology, dark energy is known as the cause of the acceleration of the expansion of the Universe. In this model, there are predictions about the redshift transition to the accelerated expansion of the Universe [

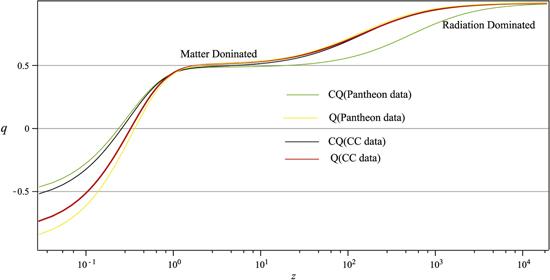

15,

16]. In fact, it is believed that the transition from non-relativistic matter dominant to dark energy dominant has led to the transition from deceleration expansion to accelerated expansion. Many studies have been done to find the redshift transition time [

17]. Numerous experiments are underway and many theoretical methods have been proposed to investigate cosmic acceleration. Methods such as the kinematic approach [

18–

20] which is based on parameterize the decelerating acceleration

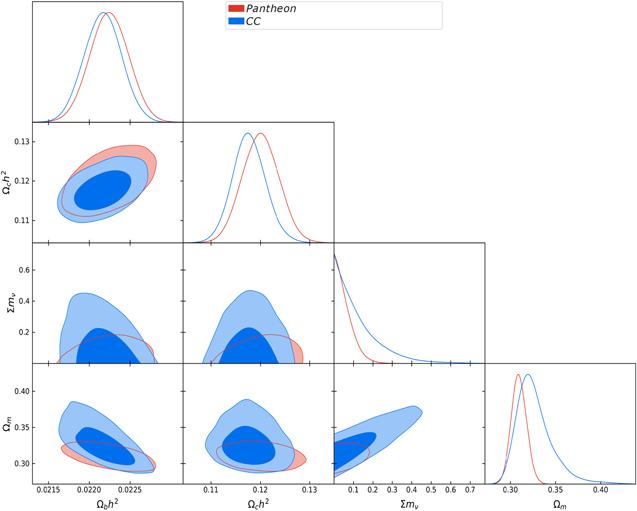

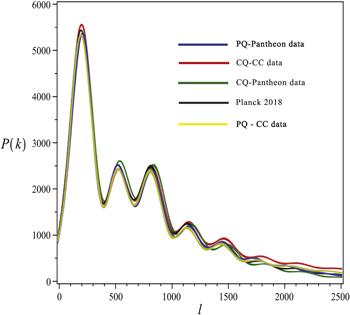

q as a function of the redshift (

z). However, until recently, determining this redshift was possible was not acceptable because there were no high-quality data at sufficiently high redshifts (the redshift transition in standard dark energy cosmological models). In this paper, we first put constraints on the total mass of neutrinos and then estimate the Deceleration–Acceleration phase redshift transition using the coupling canonical scalar field with neutrinos. Then we investigate the effect of non-relativistic on the CMB power spectrum with the use of the CAMB code.