Figure

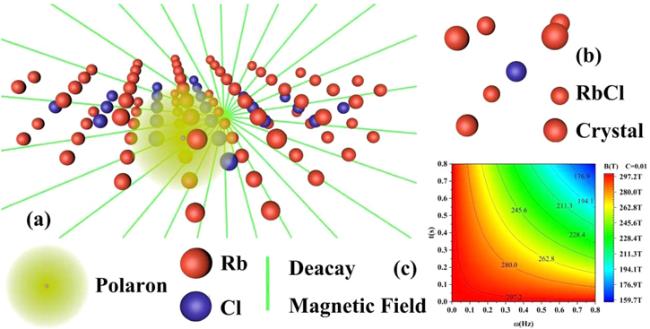

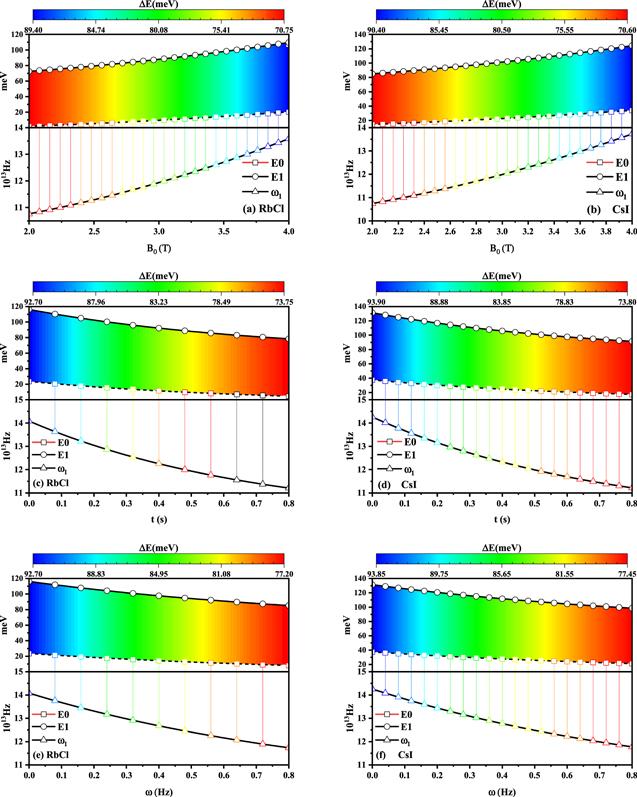

3 shows a few parameters of the asymmetric Gaussian potential: $\omega =0.6\,{\rm{Hz}}$, $t=0.3\,{\rm{s}}$, $R=0.6\,{\rm{nm}}$, and $V=3\,{\rm{meV}}.$ The ground state energy, first excited state energy, excitation energy, and transition frequency of the magnetopolaron are the increasing functions of the initial magnetic induction intensity and decreasing functions of decay time and circular frequency, as shown in figure

3. Because the magnetic induction strength of the decaying magnetic field increases with the initial magnetic induction strength and decreases with circle frequency and decay time by formula $B=\tfrac{{B}_{0}\exp \left(-\omega t\right)}{C},$ and the magnetic field has a strong limiting effect on the polaron. The magnetic induction strength will be enhanced to limit the effect of the magnetic field on the polaron resulting in stronger coupling with the electron–phonon and an increase in polaron energy, polaron ground state energy, first excited state, excitation energy, and transition frequency.