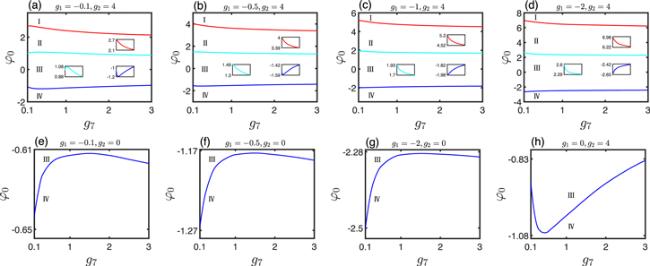

In figure

4, the regions of existence of various waves as functions of

g7 and

φ0 are shown, and details of the change of the third boundary curve are also discussed. From figures

4(a)–(d), we find that the boundary curves tend to be parallel to the horizontal axis, and the region of existence of each wave broadens with decreasing

g1. These results are similar to those in figure

3. However, with the decrease of

g1, the change trend of these boundaries is completely different from that in figure

3. As shown in figure

4(a), the first and second boundary curves increase first and then decrease while the third boundary curves are completely opposite. In figure

4(b), the first one becomes a monotonic curve. In figure

4(c), the first and second boundary curves are monotonically decreasing and the third boundary curve still decreases first then increases. In figure

4(d), all these boundary curves are monotonic. To explore the factors that affect the curve change, we discuss the third boundary curves with different

g1 and

g2 in figures

4(e)–(h). When

g2 = 0, that is, the cross-interaction (saturated nonlinearity) is so weak that it can be neglected, all these curves are increasing first and then decrease, as shown in figures

4(e)–(g). However, when we take

g1 = 0 in figure

4(h), the self-interaction (Kerr nonlinearity) can be neglected and the curve decreases first then increases. From these results, we know that the different change trend of boundary curves in figures

4(a)–(c) is mainly caused by the saturated nonlinearity. When

g1 < − 1, the changing trend of the curve is dominated by self-interaction and there is only a monotonous trend. Of course, the range of variation of the curve is affected by the saturation nonlinearity.