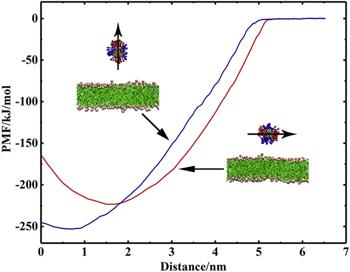

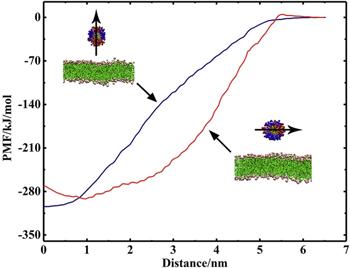

Furthermore, the PMF of

${\mathrm{NP}}_{104/50}^{25}$ interacting with the lipid bilayer was calculated (figure

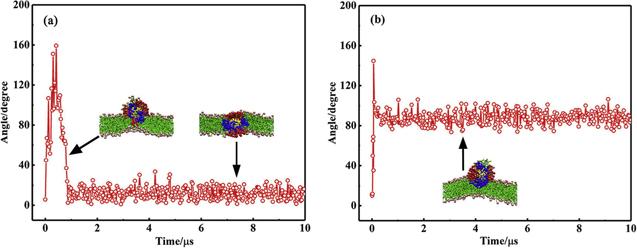

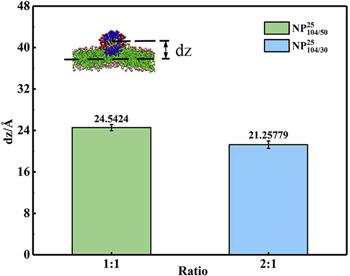

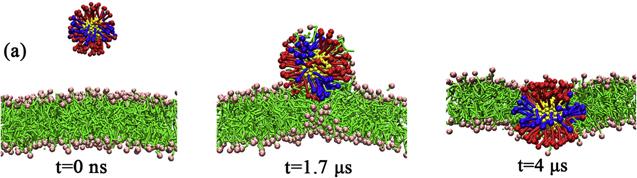

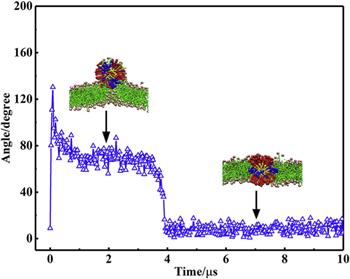

6). The results show that the binding free energies for the two interaction states of

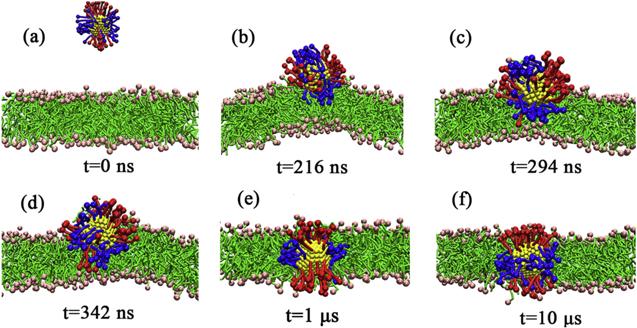

${\mathrm{NP}}_{104/50}^{25}$ with the lipid bilayer are approximately identical in magnitude, which means that the NP can both be stably adsorbed on the bilayer surface and be stably embedded in the lipid bilayer (as shown in figure

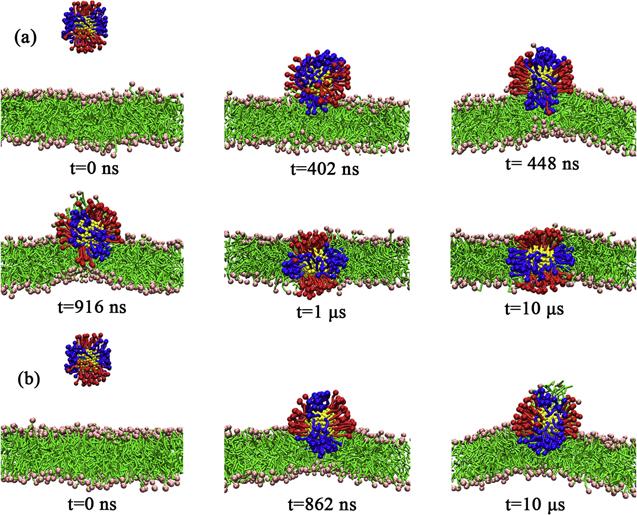

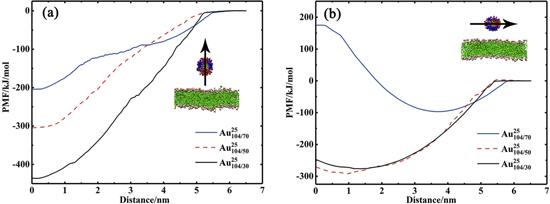

4). When the NP is inserted into the bilayer, it is inevitably accompanied by the bending of the ligands and the rearrangement of lipid molecules in the bilayer. For

${\mathrm{NP}}_{70/35}^{25}$, the ligand density is relatively low and the spacing between the ligands is relatively large. Therefore, the ligands can be bent and adjusted relatively freely during the insertion of

${\mathrm{NP}}_{70/35}^{25}$. Additionally, the effective size of

${\mathrm{NP}}_{70/35}^{25}$ is relatively small and thus the lipid packing in the bilayer does not need to be adjusted drastically during the process of the insertion of the NP into the bilayer. Therefore,

${\mathrm{NP}}_{70/35}^{25}$ can be easily embedded into the bilayer. On the contrary, for

${\mathrm{NP}}_{104/50}^{25}$, as the number of ligands increases, the spacing between the ligands becomes smaller and the degree of freedom of ligand bending is restricted during the process of the insertion of the NP into the bilayer, which indicates that the insertion of

${\mathrm{NP}}_{104/50}^{25}$ into the bilayer will cause a large deformation of the ligands and increase the free energy of the system. Additionally, as the density of the ligands increases, the effective size of

${\mathrm{NP}}_{104/50}^{25}$ increases and the insertion of the NP into the bilayer will cause a large adjustment of lipid packing, which will also increase the free energy of the system. Therefore, the PMF of

${\mathrm{NP}}_{104/50}^{25}$ adsorbed on the bilayer surface and the PMF of

${\mathrm{NP}}_{104/50}^{25}$ embedded in the bilayer are approximately identical, i.e.,

${\mathrm{NP}}_{104/50}^{25}$ may either be embedded in the bilayer or be adsorbed on the bilayer surface (as shown in figure

4).