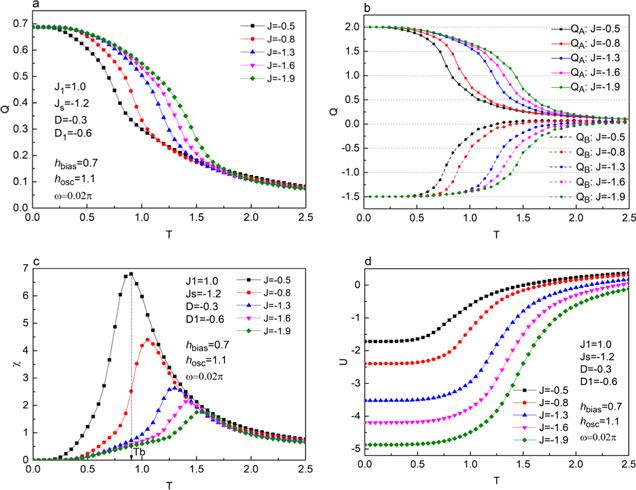

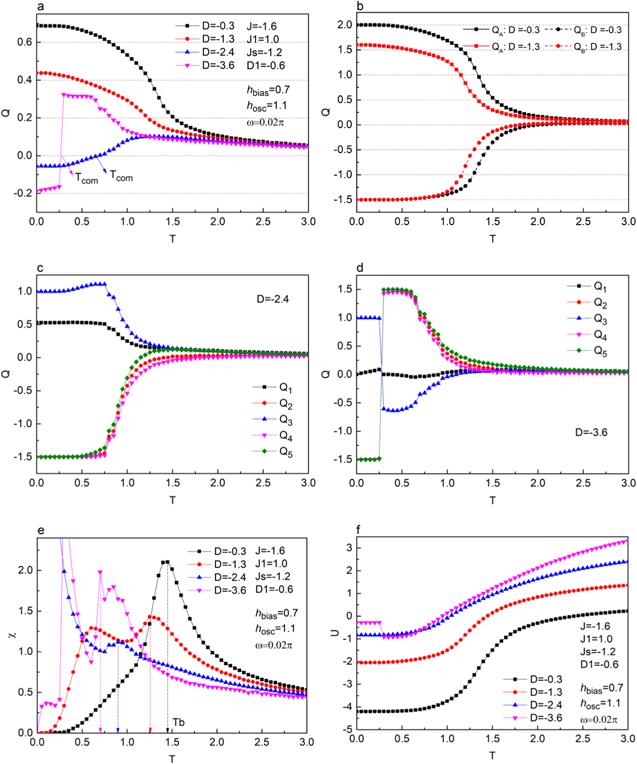

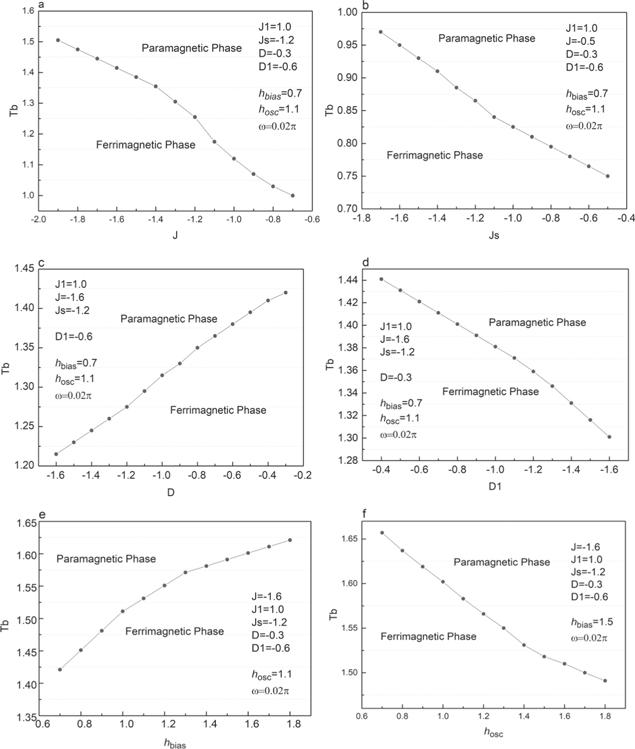

Figure

2 shows the variations in the dynamic order parameters of the system when the exchange-coupling

J changes, and the remaining parameters are set to

Js = −1.2,

J1 = 1.0,

hbias = 0.7,

hosc = 1.1,

D = −0.3,

D1 = −0.6, and

ω = 0.02

π. Figure

2(a) shows the functional relationship between the average total dynamic order parameters (

Q) and temperature (

T) for different values of

J. Only one saturation value (

Qs =11/16) exists on all the

Q −

T curves. The curves begin at this value and then gradually decline to a constant value. The effects of

J on

Q are not obvious when

T < 0.25 or

T > 0.75. When 0.25 <

T < 0.75,

Q increases slowly with the increase in

J. Moreover, for a certain

T, the higher the

J, the higher the

Q, which indicates that strong exchange coupling accelerates the order energy of the system. From figure

2(b), the saturation values of

QA and

QB at

T = 0,

QA = 2.0, and

QB = −1.5, can be observed. Therefore,

QS = (30 × 2 + 18 × (−3/2))/48 = 11/16. Furthermore,

QA and ∣

QB∣ decrease with the increase in

T, whereas

QA and ∣

QB∣ increase with the decrease in

J, indicating that a high

T or small

J facilitates a disordered system. As shown in figure

2(c), every

χ −

Q curve has a maximum, which corresponds to the blocking temperature

Tb, where

Tb is a physical quantity that depends on ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetic (ferrimagnetic) materials. The system is in the ferromagnetic (ferrimagnetic) phase when

T <

Tb and in the paramagnetic phase when

T >

Tb. As

T increases, the

χ curves gradually shift to the high-temperature region. This behavior can be explained by an increase in the order energy of the system owing to the increase in

J. Therefore, an increased amount of thermal energy is required to bring the system to disorder. In figure

2(d), the

U curves are observed to increase as

T increases and maintain a similar change rule. More specifically, when the temperature is low,

U maintains a constant value. With the increase in

T,

U increases rapidly and subsequently slows. In addition, we observe that for the same temperature,

U decreases as ∣

J∣ increases.