1. Introduction

2. Mathematical modeling

3. The existence of the positive equilibrium points

3.1. The case for 0 ≤ I ≤ Ic

When $0\leqslant I\leqslant {I}_{c}$, no matter whether ${R}_{0}\lt 1,{R}_{0}=1$ or ${R}_{0}\gt 1$, system ${(5)}_{1}$ always has one positive equilibrium point.

From the first equation of system $(8)$, we get $S=\displaystyle \frac{(1-r)A}{\beta I+\mu }$. By substituting $S=\displaystyle \frac{(1-r)A}{\beta I+\mu }$ into the second equation of system $(8)$, we have

3.2. The case for 0 < Ic < I

When $I\gt {I}_{c}$, suppose ${I}_{1}^{* }$, ${I}_{2}^{* }$ (${I}_{1}^{* }\lt {I}_{2}^{* }$) are two roots of ${g^{\prime} }_{2}(I)=3{b}_{0}{I}^{2}\,+\,2{b}_{1}I+{b}_{2}\,=\,0$. Letting the positive equilibria ${E}_{i}=({S}_{i},{I}_{i}),i\,=\,3,4,5,6,7$, then the following results hold.

| 1. | (1) Suppose ${b}_{2}\gt 0$, then ${{\rm{\Delta }}}_{2}\gt 0$, we have the following results. (a) If ${b}_{3}\geqslant 0$, system ${(5)}_{2}$ has one positive equilibrium point E5. (b) If ${b}_{3}\lt 0$ and ${g}_{2}({I}_{2}^{* })=0$, system ${(5)}_{2}$ has one positive equilibrium ${E}_{4}={E}_{5}.$ (c) If ${b}_{3}\lt 0$ and ${g}_{2}({I}_{2}^{* })\gt 0$, system ${(5)}_{2}$ has two positive equilibria E4, E5. |

| 2. | (2) Suppose ${b}_{2}=0$, then ${{\rm{\Delta }}}_{2}\geqslant 0$, we have the following results. (a) If ${b}_{1}=0$ and ${b}_{3}\gt 0$, then ${{\rm{\Delta }}}_{2}=0$, system ${(5)}_{2}$ has one positive equilibrium E6. (b) If ${b}_{1}\ne 0$ and ${b}_{3}\gt 0$, then ${{\rm{\Delta }}}_{2}\gt 0$, system ${(5)}_{2}$ has one positive equilibrium E5. (c) If ${b}_{1}\gt 0$, ${b}_{3}\lt 0$ and ${g}_{2}({I}_{2}^{* })=0$, then ${{\rm{\Delta }}}_{2}\gt 0$, system ${(5)}_{2}$ has one positive equilibrium ${E}_{4}={E}_{5}.$ (d) If ${b}_{1}\gt 0$, ${b}_{3}\lt 0$ and ${g}_{2}({I}_{2}^{* })\gt 0$, then ${{\rm{\Delta }}}_{2}\gt 0$, system ${(5)}_{2}$ has two positive equilibria E4, E5. |

| 3. | (3) Suppose ${b}_{2}\lt 0$, then we have the following results. (i) If ${{\rm{\Delta }}}_{2}\gt 0$, ${b}_{1}\gt 0$ and ${b}_{3}\gt 0$, we continue to discuss. (a) If ${g}_{2}({I}_{1}^{* })\gt 0$, system ${(5)}_{2}$ has one positive equilibrium E5. (b) If ${g}_{2}({I}_{1}^{* })\lt 0,{g}_{2}({I}_{2}^{* })\gt 0$, system ${(5)}_{2}$ has three positive equilibria E3, E4, E5. (c) If ${g}_{2}({I}_{1}^{* })\lt 0,{g}_{2}({I}_{2}^{* })\lt 0$, system ${(5)}_{2}$ has one positive equilibrium E3. (d) If ${g}_{2}({I}_{1}^{* })=0,{g}_{2}({I}_{2}^{* })\gt 0$, system ${(5)}_{2}$ has two positive equilibria ${E}_{3}={E}_{4}$, E5. (e) If ${g}_{2}({I}_{1}^{* })\lt 0,{g}_{2}({I}_{2}^{* })=0$, system ${(5)}_{2}$ has two positive equilibria E3, ${E}_{4}={E}_{5}$. (ii) If ${{\rm{\Delta }}}_{2}\gt 0$, ${b}_{1}\gt 0$ and ${b}_{3}\leqslant 0$, we continue to discuss. (a) If ${g}_{2}({I}_{1}^{* })\lt 0,{g}_{2}({I}_{2}^{* })=0$, system ${(5)}_{2}$ has one positive equilibrium ${E}_{4}={E}_{5}.$ (b) If ${g}_{2}({I}_{1}^{* })\lt 0,{g}_{2}({I}_{2}^{* })\gt 0$, system ${(5)}_{2}$ has two positive equilibria E4, E5. (iii) If ${{\rm{\Delta }}}_{2}\gt 0$, ${b}_{1}=0$ and ${b}_{3}\geqslant 0$, system ${(5)}_{2}$ has one positive equilibrium E5. (iv) If ${{\rm{\Delta }}}_{2}\gt 0$, ${b}_{1}=0$ and ${b}_{3}\lt 0$, we continue to discuss. (a) If ${g}_{2}({I}_{2}^{* })=0$, system ${(5)}_{2}$ has one positive equilibrium ${E}_{4}={E}_{5}.$ (b) If ${g}_{2}({I}_{2}^{* })\gt 0$, system ${(5)}_{2}$ has two positive equilibria E4, E5. (v) If ${{\rm{\Delta }}}_{2}\gt 0$, ${b}_{1}\lt 0$ and ${b}_{3}\gt 0$, system ${(5)}_{2}$ has one positive equilibrium E5. (vi) If ${{\rm{\Delta }}}_{2}\leqslant 0$ and ${b}_{3}\gt 0$, system ${(5)}_{2}$ has one positive equilibrium E7. |

4. Bifurcation analysis without diffusion

Assume the condition that ${b}_{1}\gt 0$, ${b}_{2}\lt 0$, ${b}_{3}\gt 0$, ${{\rm{\Delta }}}_{2}\gt 0$ and ${A}_{11}({E}^{* })\ne 0$. In addition, if $\displaystyle \frac{{p}_{10}({q}_{01}{q}_{11}+{p}_{01}{q}_{11}-{p}_{10}{q}_{02})}{{p}_{10}^{2}+{p}_{01}{q}_{10}}\ne 0$, then system ${(12)}_{2}$ undergoes a saddle-node bifurcation as ${g}_{2}({I}^{* })={g^{\prime} }_{2}({I}^{* })=0$, where

From Theorem

5. Local stability and bifurcation analysis with diffusion

Assume ${E}^{* }=({S}^{* },{I}^{* })$ is any equilibrium point of system (5). Denote

The positive equilibrium E2 of system (5) is locally asymptotically stable.

Whatever R0 is, we find $g{{\prime} }_{1}({I}_{2})\lt 0$ always holds. Moreover, according to the same method in theorem

Assume that $({H}_{1})$ holds. Then, for system (5), we have the following results.

| i | (i) E4 is unstable. |

| ii | (ii) If ${A}_{11}({E}_{3})\gt 0$, then E3 is locally asymptotically stable as $\gamma \gt {\gamma }_{1};$ if ${A}_{11}({E}_{3})\lt 0$, then E3 is unstable. |

| iii | (iii) If ${A}_{11}({E}_{5})\gt 0$, then E5 is locally asymptotically stable as $\gamma \gt {\gamma }_{3};$ if ${A}_{11}({E}_{5})\lt 0$, then E5 is unstable. |

| i | (i) According to theorems $\begin{eqnarray*}\begin{array}{l}{g^{\prime} }_{2}({I}_{4})\gt 0,\\ {A}_{2}^{(0)}({E}_{4})={A}_{22}({E}_{4})\\ \quad =\,-\displaystyle \frac{1}{c+{I}_{4}-{I}_{c}}{g^{\prime} }_{2}({I}_{4})\lt 0.\end{array}\end{eqnarray*}$ Therefore, equation ( |

| ii | (ii) Firstly, we denote $\begin{eqnarray*}\begin{array}{l}\gamma =\displaystyle \frac{{d}_{2}}{{d}_{1}},\\ G({I}_{3})=\displaystyle \frac{{rA}}{{I}_{3}}+\displaystyle \frac{{c}^{2}}{{\left(c+{I}_{3}-{I}_{c}\right)}^{2}}-\displaystyle \frac{c({I}_{3}-{I}_{c})}{{I}_{3}(c+{I}_{3}-{I}_{c})},\\ {\gamma }_{0}=-\displaystyle \frac{1}{\beta {I}_{3}+\mu }G({I}_{3}),\\ {\gamma }_{1}=\displaystyle \frac{4{A}_{22}({E}_{3})-2(\beta {I}_{3}+\mu )G({I}_{3})-\sqrt{\overline{{{\rm{\Delta }}}_{1}}}}{2{\left(\beta {I}_{3}+\mu \right)}^{2}},\\ {\gamma }_{2}=\displaystyle \frac{4{A}_{22}({E}_{3})-2(\beta {I}_{3}+\mu )G({I}_{3})+\sqrt{\overline{{{\rm{\Delta }}}_{1}}}}{2{\left(\beta {I}_{3}+\mu \right)}^{2}}.\end{array}\end{eqnarray*}$ |

| a | (a) Suppose ${A}_{11}({E}_{3})\gt 0$, it is obvious that ${A}_{1}^{(i)}({E}_{3})$ $={A}_{10}({E}_{3}){l}_{i}^{2}$ $+{A}_{11}({E}_{3})$$=({d}_{1}+{d}_{2}){l}_{i}^{2}$ $+{A}_{11}({E}_{3})\gt 0,i\in {N}_{0}$. |

Assume $({H}_{1})$ and ${A}_{11}({E}_{5})\gt 0$ hold. If $\gamma \lt {\gamma }_{3}$, then E5 is Turing unstable.

From theorem

Assume that $({H}_{1})$ and $\gamma \gt {\gamma }_{3}$ hold, moreover, suppose there exists ${\beta }^{* }\gt 0$ satisfying that ${A}_{11}({E}_{5})=0$ at $\beta ={\beta }^{* }$, and $\displaystyle \frac{{\rm{d}}{A}_{11}({E}_{5})}{{\rm{d}}\beta }{| }_{\beta ={\beta }^{* }}\ne 0$. If $\beta ={\beta }^{* }$, then system (5) undergoes a spatially homogeneous Hopf bifurcation at E5. Moreover, if σ > 0, then the direction of Hopf bifurcation is supercritical, that is to say, the periodic solutions are unstable; if $\sigma \lt 0$, then the direction of Hopf bifurcation is subcritical, that is to say, the periodic solutions are locally asymptotically stable, where

For system (5), under the condition $({H}_{1})$, the positive equilibrium point E5 exists. First, we will prove the existence of Hopf bifurcation at E5. We assume there exists ${\beta }^{* }\gt 0$, when $\beta ={\beta }^{* }$, ${A}_{11}({E}_{5})=0$ holds. Then for i0 = 0, we have

When $({H}_{1}),{C}_{11}(E^{\prime} )\gt 0$ and ${C}_{22}(E^{\prime} )\gt 0$ hold, system (5) undergoes a discontinuous Hopf bifurcation at $E^{\prime} $.

From Theorem

6. Simulation

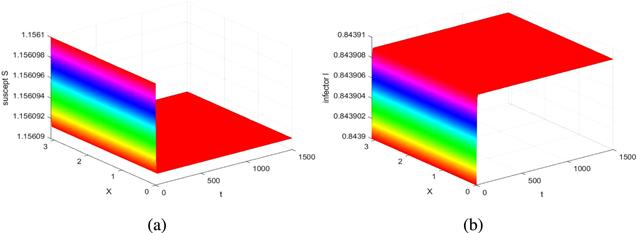

6.1. Case 1: 0 ≤ I < Ic

Figure 1. The equilibrium point E2 is locally asymptotically stable. |

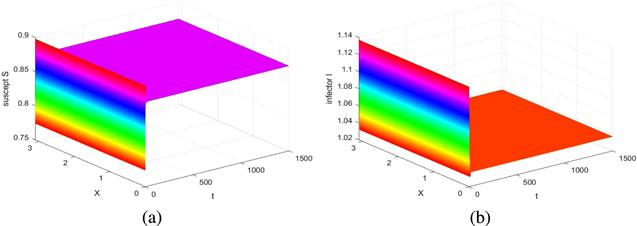

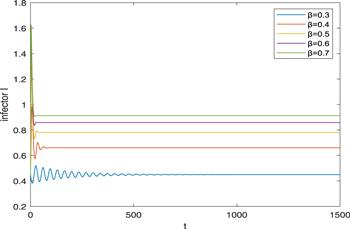

6.2. Case 2: I > Ic

Figure 2. The equilibrium point E5 is locally asymptotically stable. |

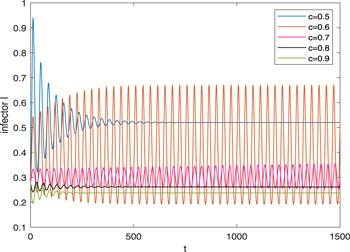

Figure 3. The influence of rumor propagation rate β on rumor spreaders. |

Figure 4. The equilibrium point E5 is unstable. |

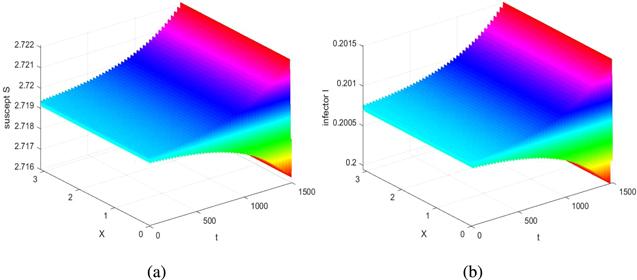

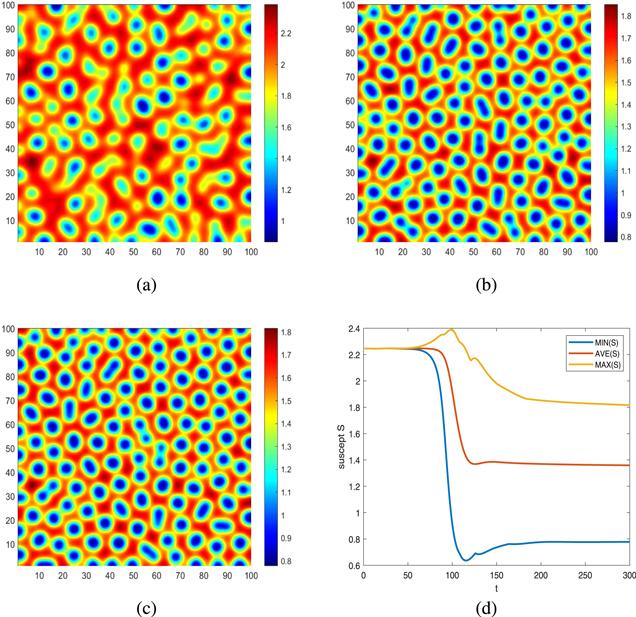

Figure 5. The Turing instability of E5. |

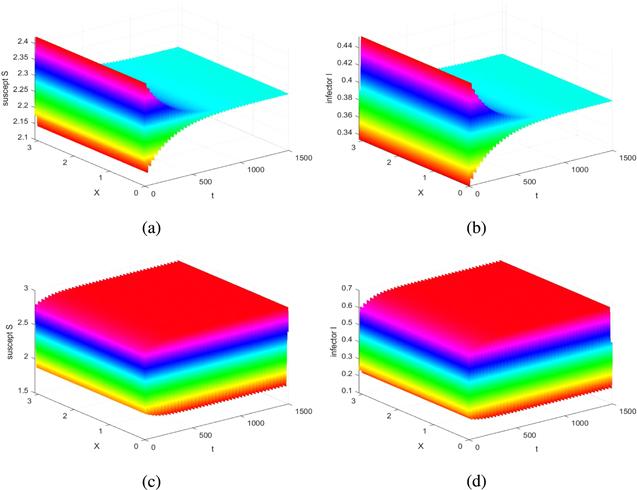

Figure 6. The change of stabilities for the equilibrium point E5. |

Figure 7. The Hopf bifurcation at E5. |