1. Introduction

2. Thermodynamics

3. Phase transition and phase structure

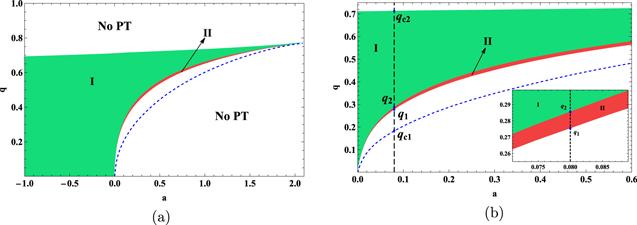

Figure 1. Regions of different phase transitions for q and a. Left Panel (a): The white region represents the system without phase transition (PT). The green region I corresponds to the case that a single first-order phase transition occurs. The reentrant phase transition happens in the red region II. The blue dashed line corresponds to the unstable critical point for a > 0, which does not present the occurrence of phase transitions. Right Panel (b): The black dashed line a = 0.08 intersects the blue dashed line at qc1, and intersects the boundary of regions at q1, q2, qc2, respectively. The cavity radius is set to be rB = 3. |

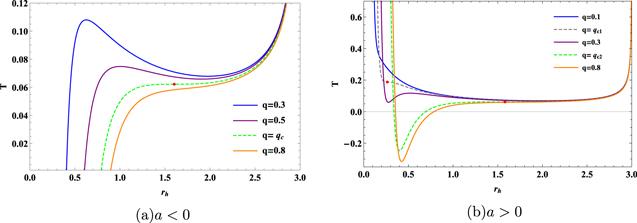

Figure 2. Temperature curve of the Euler–Heisenberg black hole in a cavity versus horizon radius for different values of q. Left Panel (a): The parameter a = −1 , and the charge q is equal to 0.3, 0.5, 0.6909 and 0.8, respectively; Right Panel (b): The parameter a = 0.08, and the charge q is equal to 0.1, 0.1839, 0.3, 0.7098 and 0.8, respectively. The cavity radius rB is set to be 3. |

3.1. a > 0 case

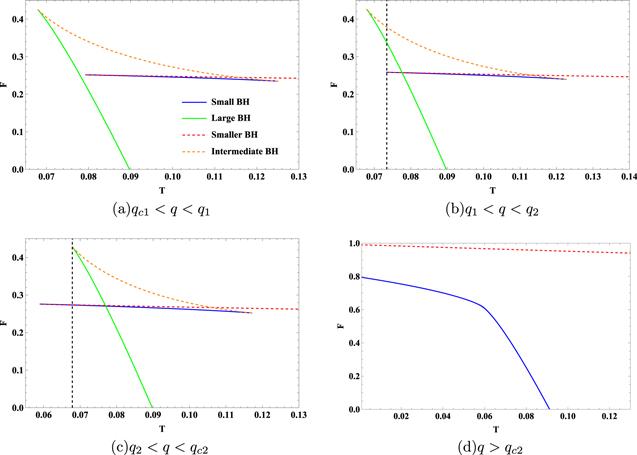

Figure 3. The free energy versus the temperature. Upper Left Panel (a): No phase transition occurs for qc1 < q < q1, where we set q = 0.279. Upper Right Panel (b): The reentrant phase transition for q1 < q < q2, where we set q = 0.285. Lower Left Panel (c): The first-order phase transition for q2 < q < qc2, and we choose q = 0.3 as an example. Lower Right Panel (d): No phase transition occurs for q > qc2, where small and large BH phases can not be distinguished. We set q = 0.8 here. The dashed curves represent unstable branches, while the solid curves stand for stable or metastable BHs. We set a = 0.08 and rB = 3. |

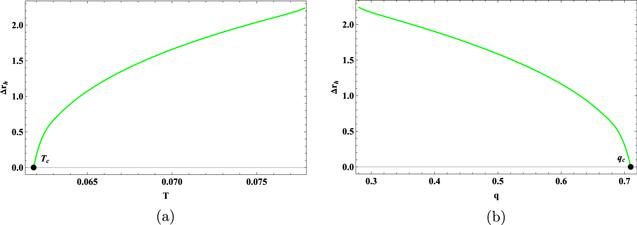

Figure 4. The sudden change Δrh when the black hole comes up a first-order phase transition. Left Panel (a): As the temperature decreases, the Δrh decreases to zero. Right Panel (b): As the charge increases, the Δrh decreases to zero. The QED parameter and radius of the cavity are set to be a = 0.08 and rB = 3. |

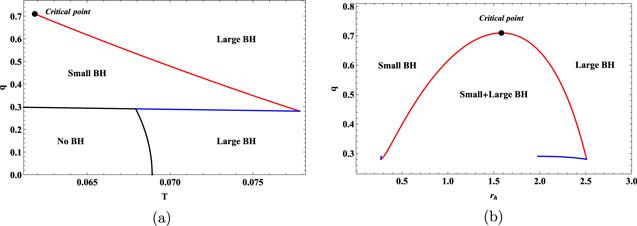

Figure 5. Phase diagram for a > 0 by taking the charge q as an analogy of the pressure. Left Panel (a): First-order coexistence curve (red solid) and zeroth-order phase transition curve (blue solid) in the q-T plane. The black curve separates the regions with and without black holes. The coexistence curve separates black holes into small and large BH phases, and ends at the critical point of the small/large BH phase transition. Right Panel (b): The phase structure in the q-rh plane. We choose the parameter a = 0.08 and the radius of cavity rB = 3. |

3.2. a < 0 case

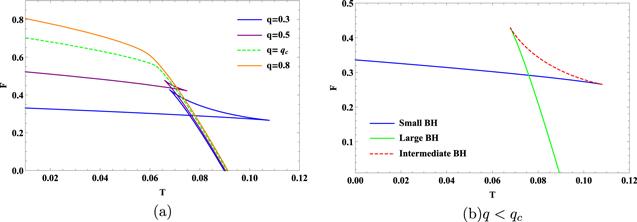

Figure 6. Left Panel (a): The free energy versus the temperature for q = 0.3 (blue solid curve), q = 0.5 (purple solid curve), q = 0.6909 (green dashed curve) and q = 0.8 (orange solid curve). Right Panel (b): The free energy versus the temperature for q < qc, where we choose q = 0.3. The small/large BH phase transition occurs at the intersection of the blue and green solid curve, which represents the stable small BH phase and the stable large BH phase, respectively. The red dashed curve is the unstable intermediate BH branch. We set a = −1 and rB = 3 here. |

Figure 7. Phase diagram for a < 0 by taking charge q as an analogy of pressure. Left Panel (a): First-order coexistence curve in the q-T plane, which separates the black hole into small BH phase and large BH phase. The coexistence curve ends at the critical point of the small/large BH phase transition. Right Panel (b): The phase structure in the q-rh plane. With the increase of radius, small and large BHs coexist in the region bounded by the red curve and the axis. We choose the parameter a = −1 and the cavity radius rB = 3. |

4. Ruppeiner geometry and microstructure

4.1. a > 0 case

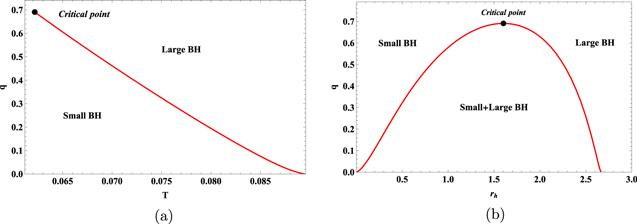

Figure 8. The Ruppeiner invariant R versus T with a fixed a = 0.08. Upper Left Panel (a): For qc1 < q < q1, we set q = 0.279. Upper Right Panel (b): q = 0.285, in the range of q1 < q < q2. Lower Left Panel (c): q = 0.3 is chosen as an example for q2 < q < qc2. In these three panels, there are four black hole solutions, and the red/orange dashed curves represent unstable smaller BH and intermediate BH, while the blue/green solid curves represent stable small/large BH, and the black dashed curve corresponds to the temperature of the first-order phase transition. Lower Right Panel (d): q > qc2, where we set q = 0.8, there is only one stable solution (blue solid curve). |

4.2. a < 0 case

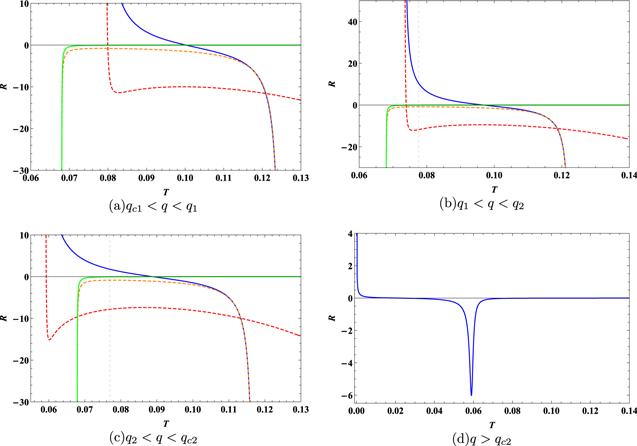

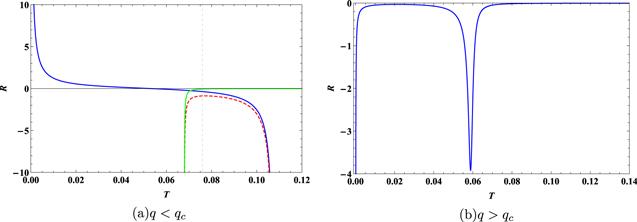

Figure 9. The Ruppeiner invariant R versus temperature T with fixed a = −1. Left Panel (a): For q < qc, there are three black hole solutions, and we choose q = 0.3 for visualization. The red dashed curve represents the unstable intermediate BH, while the blue/green solid curve represents the stable small/large BH, and the black dashed curve corresponds to the temperature of the first-order phase transition. Right Panel (b): q > qc, where q = 0.8 to show the details, there is only one solution and it is stable (blue solid curve). |

Figure 10. The behavior of the Ruppeiner invariant R along the first-order coexistence curve. Left Panel (a): a = 0.08, R depends on q along the first-order coexistence curve in figure 5(a). Right Panel (b): a = −1, the first-order coexistence curve is in figure 7(a). The green curve represents the small BH, while the red curve represents the large BH. |