1. Introduction

2. Modified f(R, φ) field equations via Karmarkar condition

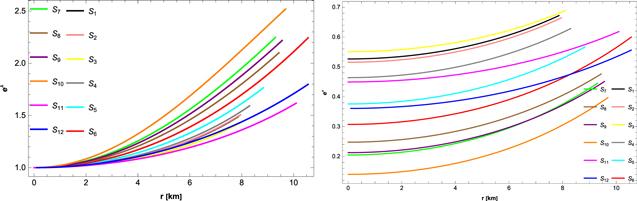

Figure 1. Behavior of metric potential grr and gtt. |

3. Junction conditions

| • | The behavior of ρ, pr and pt should be optimistic, continuous, and maxima in the apex. |

| • | The plots of $\tfrac{{\rm{d}}{p}_{r}}{{\rm{d}}r},$ $\tfrac{{\rm{d}}{p}_{t}}{{\rm{d}}r}$ and $\tfrac{{\rm{d}}\rho }{{\rm{d}}r}$ all have to be non-positive. |

| • | Each one of the energy parameters should be accomplished. |

| • | The equilibrium consistency requirement must be met by all of the forces. |

| • | The parameters vr2 and vt2 have to be in the range [0, 1]. |

Table 1. Unknown parameters of the compact structures. |

| Star model | M (MΘ) | R (km) | b (km) | a (km) | B (km) | A (km) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4U 1538-52 (S1) | 0.87 ± 0.07 [72] | 7.866 ± 0.21 | −0.000 105 899 | 0.122 14 | 0.044 3339 | −25.0131 |

| SAX J1808.4-3658 (S2) | 0.9 ± 0.3 [72] | 7.951 ± 1.0 | −0.000 920 891 | 0.079 3101 | 0.036 4385 | −0.851 084 |

| Her X-1 (S3) | 0.85 ± 0.15 [72] | 8.1 ± 0.41 | −0.000 977 202 | 0.072 6952 | 0.034 4393 | −0.538 845 |

| LMC X-4 (S4) | 1.04 ± 0.09 [72] | 8.301 ± 0.2 | −0.000 705 186 | 0.083 8586 | 0.036 7192 | −1.502 07 |

| SMC X-4 (S5) | 1.29 ± 0.05 [72] | 8.831 ± 0.09 | −0.000 366 545 | 0.093 4356 | 0.037 2694 | −4.137 13 |

| Cen X-3 (S6) | 1.49 ± 0.08 [72] | 9.178 ± 0.13 | −0.000 104 682 | 0.103 164 | 0.037 8044 | −18.0737 |

| 4U 1608-52(S7) | 1.74 ± 0.14 [73] | 9.3 ± 1.0 | 0.000 368 416 | 0.127 851 | 0.040 0518 | 7.402 05 |

| PSR J1903 + 327 (S8) | 1.667 ± 0.021 [72] | 9.48 ± 0.03 | 0.000 142 764 | 0.113 994 | 0.038 346 | 15.807 |

| Vela X-1 (S9) | 1.77 ± 0.08 [72] | 9.56 ± 0.08 | 0.000 306 813 | 0.122 018 | 0.038 7589 | 8.168 31 |

| PSR J1614-2230 (S10) | 1.97 ± 0.04 [74] | 9.69 ± 0.2 | −0.000 739 078 | 0.145 463 | 0.040 07 | 4.317 39 |

| EXO 1785-248 (S11) | 1.30 ± 0.2 [74] | 10.10 ± 0.44 | −0.000 447 232 | 0.070 8703 | 0.030 5887 | −1.753 21 |

| 4U 1820-30 (S12) | 1.58 ± 0.06 [75] | 10.56 ± 0.10 | −0.000 2209 | 0.080 4744 | 0.031 5431 | −5.144 66 |

4. Physical analysis of f(R, φ) gravity model

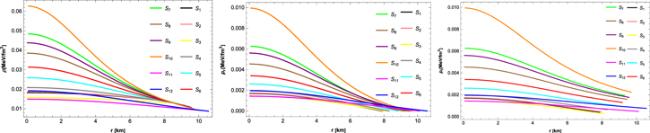

4.1. Energy density and pressure progression

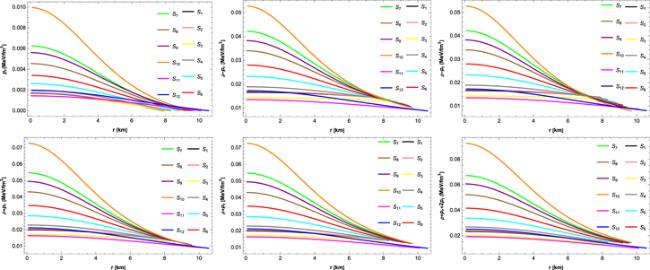

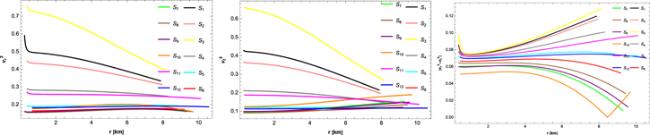

Figure 2. Graphical variations of ρ, pr and pt for α = 0.01, χ = 1 × 107, w0 = 1, m = 1, β = 1 for (S1, S2, S3, S4, S5, S7, S8, S10, S11, S12) and β = 1.5 for (S6, S9). |

Figure 3. Evolution of $\tfrac{{\rm{d}}\rho }{{\rm{d}}r},$ $\tfrac{{\rm{d}}{p}_{r}}{{\rm{d}}r}$ and $\tfrac{{\rm{d}}{p}_{t}}{{\rm{d}}r}$ for α = 0.01, χ = 1 × 107, w0 = 1, m = 1, β = 1 for (S1, S2, S3, S4, S5, S7, S8, S10, S11, S12) and β = 1.5 for (S6, S9). |

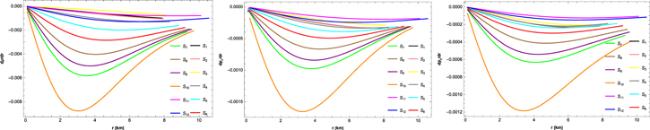

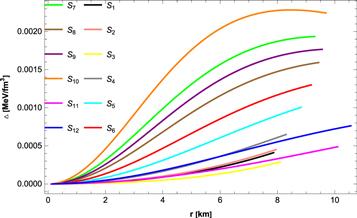

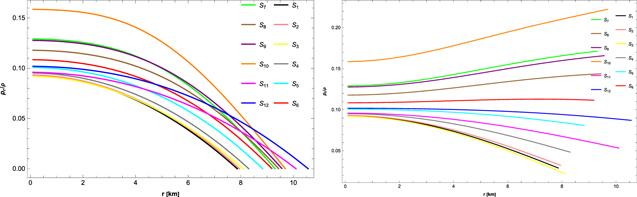

4.2. Anisotropy

Figure 4. Evolution of anisotropy for α = 0.01, χ = 1 × 107, w0 = 1, m = 1, β = 1 for (S1, S2, S3, S4, S5, S7, S8, S10, S11, S12) and β = 1.5 for (S6, S9). |

4.3. Tolman-Oppenheimer-Volkoff equation for f(R, T) gravity

| • | ${{ \mathcal F }}_{a}=\tfrac{2}{r}{\rm{\Delta }}$ symbolize anisotropic force, |

| • | ${{ \mathcal F }}_{h}=-\tfrac{{\rm{d}}{p}_{r}}{{\rm{d}}r}$ represents hydrostatic force, |

| • | ${{ \mathcal F }}_{g}=-\tfrac{{\nu }^{{\prime} }}{r}(\rho +{p}_{r})$ is gravitational force. |

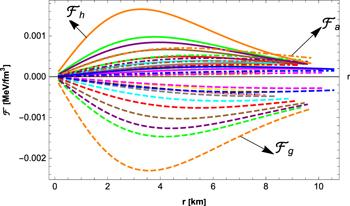

Figure 5. Behavior of ${{ \mathcal F }}_{h}$, ${{ \mathcal F }}_{g}$ and ${{ \mathcal F }}_{a}$ for α = 0.01, χ = 1 × 107, w0 = 1, m = 1, β = 1 for (S1, S2, S3, S4, S5, S7, S8, S10, S11, S12) and β = 1.5 for (S6, S9). |

4.4. Energy conditions

Figure 6. Evolution of energy bonds for α = 0.01, χ = 1 × 107, w0 = 1, m = 1, β = 1 for (S1, S2, S3, S4, S5, S7, S8, S10, S11, S12) and β = 1.5 for (S6, S9). |

4.5. Equation of state (EoS) factors

Figure 7. Evolution of wr and wt for α = 0.01, χ = 1 × 107, w0 = 1, m = 1, β = 1 for (S1, S2, S3, S4, S5, S7, S8, S10, S11, S12) and β = 1.5 for (S6, S9). |

4.6. Mass-radius function, compactness parameter and surface redshift progression

Figure 8. Behavior of ${ \mathcal M }(r),{ \mathcal U }(r),$ and ${ \mathcal Z }{\rm{s}}$ for α = 0.01, χ = 1 × 107, w0 = 1, m = 1, β = 1 for (S1, S2, S3, S4, S5, S7, S8, S10, S11, S12) and β = 1.5 for (S6, S9). |

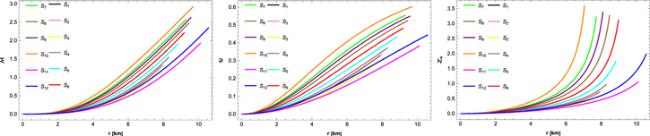

4.7. Stability analysis

Figure 9. Variations of vr2, vt2 and $| {v}_{t}^{2}-{v}_{r}^{2}| $ for α = 0.01, χ = 1 × 107, w0 = 1, m = 1, β = 1 for (S1, S2, S3, S4, S5, S7, S8, S10, S11, S12) and β = 1.5 for (S6, S9). |

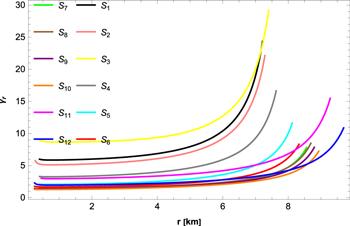

4.8. Adiabatic index

Figure 10. Behavior of γ for α = 0.01, χ = 1 × 107, w0 = 1, m = 1, β = 1 for (S1, S2, S3, S4, S5, S7, S8, S10, S11, S12) and β = 1.5 for (S6, S9). |

Table 2. The numerical values of adiabatic index d critical adiabatic index for the different compact structures. |

| Star model | M (MΘ) | R (km) | γ | γcrit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4U 1538-52 (S1) | 0.87 ± 0.07 [72] | 7.866 ± 0.21 | 336.275 | 1.553 39 |

| SAX J1808.4-3658 (S2) | 0.9 ± 0.3 [72] | 7.951 ± 1.0 | 4909.81 | 1.485 22 |

| Her X-1 (S3) | 0.85 ± 0.15 [72] | 8.1 ± 0.41 | 8521.44 | 1.474 15 |

| LMC X-4 (S4) | 1.04 ± 0.09 [72] | 8.301 ± 0.2 | 1281.51 | 1.501 45 |

| SMC X-4 (S5) | 1.29 ± 0.05 [72] | 8.831 ± 0.09 | 592.332 | 1.529 35 |

| Cen X-3 (S6) | 1.49 ± 0.08 [72] | 9.178 ± 0.13 | 468.623 | 1.551 18 |

| 4U 1608-52 (S7) | 1.74 ± 0.14 [73] | 9.3 ± 1.0 | 423.614 | 1.584 39 |

| PSR J1903 + 327 (S8) | 1.667 ± 0.021 [72] | 9.48 ± 0.03 | 440.685 | 1.570 34 |

| Vela X-1 (S9) | 1.77 ± 0.08 [72] | 9.56 ± 0.08 | 446.48 | 1.581 77 |

| PSR J1614-2230 (S10) | 1.97 ± 0.04 [74] | 9.69 ± 0.2 | 513.936 | 1.606 14 |

| EXO 1785-248 (S11) | 1.30 ± 0.2 [74] | 10.10 ± 0.44 | 1539.25 | 1.506 05 |

| 4U 1820-30 (S12) | 1.58 ± 0.06 [75] | 10.56 ± 0.10 | 1763.81 | 1.5341 |

4.9. Comparison

5. Conclusion

| • | The physical structure of both potentials in figure 1 reveals that gtt and grr are singularity-free, optimistic, and fulfill the needs, i.e. ${{\rm{e}}}^{\nu (r=0)}={\left[A-\tfrac{{aB}}{2b}\right]}^{2}$ and eλ(r=0) = 1. The response of both metric potentials reveals successful outcomes, as their graphs rise monotonically and achieve maximum levels at the border. |

| • | The consistency of ρ, pr and pt for the model under consideration is shown in figure 2. The behavior of these graphs reaches its apex in the core and then declines towards the border. |

| • | Figure 3 illustrates the gradient of ρ, pr and pt. These graphs provide non-positive depictions, confirming that our findings are reliable. |

| • | Figure 4 demonstrates that Δ > 0, indicating that anisotropic factor is repulsive in nature. This observation confirms the occurrence of astrophysical stars. |

| • | All of the forces ${{ \mathcal F }}_{h}$, ${{ \mathcal F }}_{g}$ and ${{ \mathcal F }}_{a}$ are steady and display equilibrium manners, as seen in figure 5. |

| • | Figure 6 represents the energy condition for the selected f(R, φ) model. Also, it is worth mentioning that our selected model confirms all of the relevant requirements. |

| • | It is clear from figure 7 that the composition of EoS ratios is uniform. |

| • | Figure 8 clearly shows the monotonically increasing nature of the mass function, compactness parameter, and surface redshift. |

| • | The sound velocity components vr2 and vt2 exist among [0, 1] for the exponential f(R, φ) model. Figure 9 shows that the causality conditions are appropriate for the proposed celestial configuration. |

| • | The satisfactory nature of the adiabatic parameter can be noticed in figure 10. |