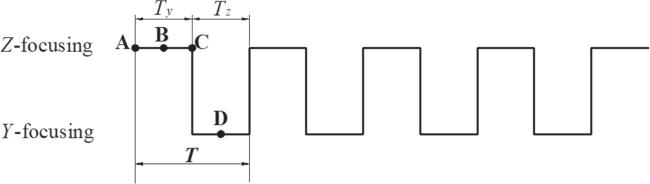

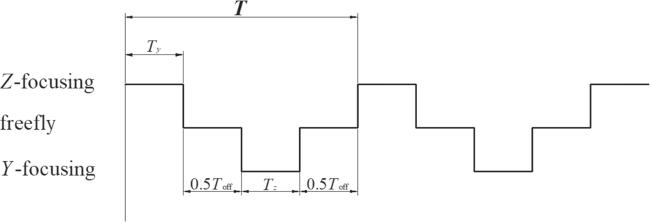

The time sequence diagram is depicted in figure

2. The currents in the coils along the

Y-axis and

Z-axis are switched on and off alternately. Here,

Ty =

Tz = 0.5

T, and

f = 1/

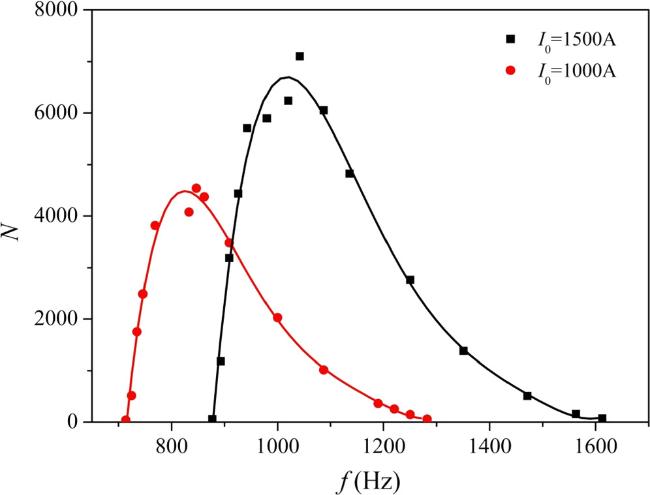

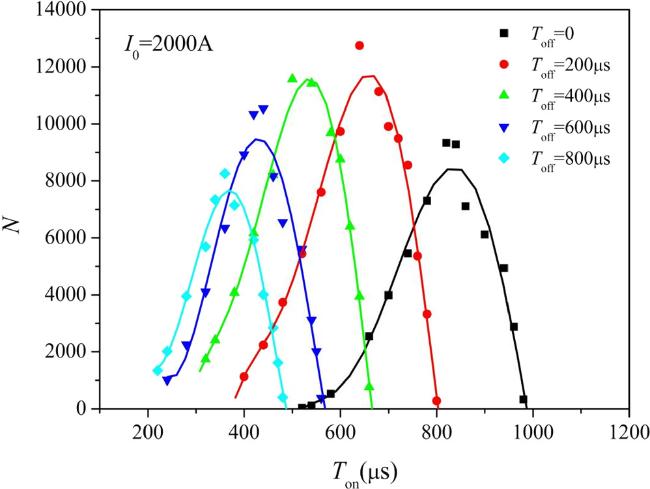

T. The number of trapped molecules versus the switching frequency (

f) after a 100 ms trapping time is indicated in figure

4. Two different values of currents (

I0) are used. The black squares and the red circles indicate that the simulation data for

I0 are equal to 1500 A and 1000 A, respectively. From figure

4, we can see that there is always an appropriate switching frequency corresponding to the maximum number of trap molecules. We need to switch the current frequently to let the molecules feel a net force [

32]. If the switching frequency is too low, the molecules will be lost along the defocusing direction. However, if we switch the current too frequently, the micromotion of the molecule becomes smaller and faster and the net force towards the trap center vanishes [

33]. The maximum number of trap molecules for

I0 = 1500 A is much larger compared to the case for

I0 = 1000 A. For the higher current, trapping works in a range between 877 and 1613 Hz. For the lower current, trapping works in a relatively narrow range between 714 and 1282 Hz. The optimal switching frequencies for

I0 = 1500 A and 1000 A are 1042 Hz and 847 Hz, respectively. The optimal frequency shifts to a higher value for a larger current.