A change in sample temperature following an adiabatic change in the applied magnetic field is known as the magnetocaloric effect (MCE), which is an inherent feature of magnetic systems [

32]. MCE has been extensively used in room and cryogenic temperature refrigeration applications [

33,

34]. In recent years, many experimental studies have found that the originally non-magnetic graphene can be made magnetic by doping magnetic transition metal atoms or through their replacement [

35,

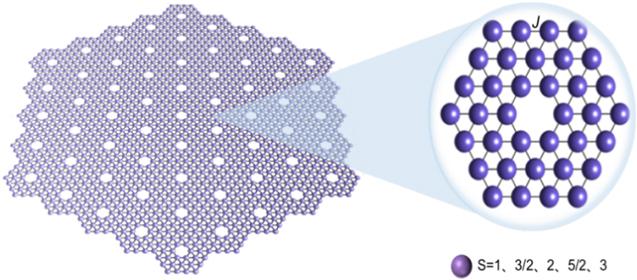

36]. In the periodic table of elements, boron and carbon are close neighbors in that they have similar chemical properties. Therefore, borophene might also have magnetism in this way, which has been successfully discussed in theory [

37]. It is shown that the magnetic moment is largest when Mn atoms are embedded. The significant effects of spin quantum numbers on the magnetic and MCE characteristics of different physical systems have been revealed through recent theoretical studies. Zhang

et al, using EFT [

38], linear spin wave approximation and the retarded Green's function method [

39] explored the effect of the spin quantum number on the phase transition temperature of graphene-like quantum dots and the magnon energy gap of a ferro-anti-ferromagnetic multisublattice system. Similarly, utilizing the Green's function method, Mi

et al carefully calculated and analyzed the role of spin quantum number on sublattice magnetization, ${\rm{N}}\acute{e}$el temperature, internal energy, and free energy of frustrated spin-

S J1-

J2 Heisenberg antiferromagnet on bcc lattice [

40]. In [

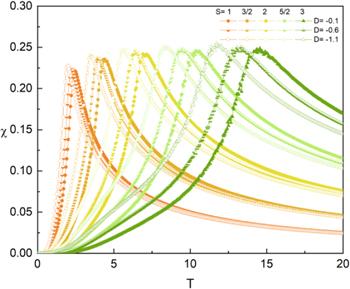

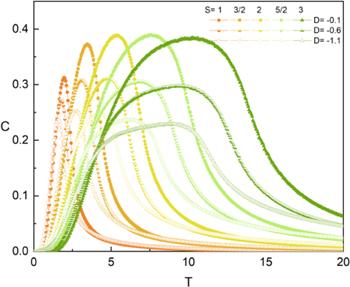

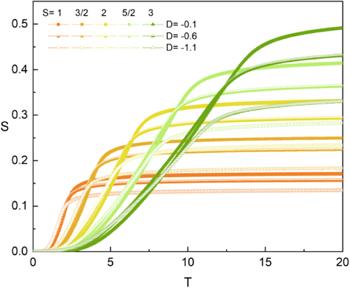

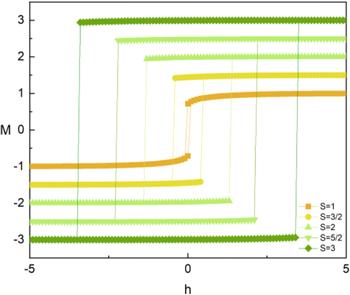

41], the effect of spin quantum numbers (

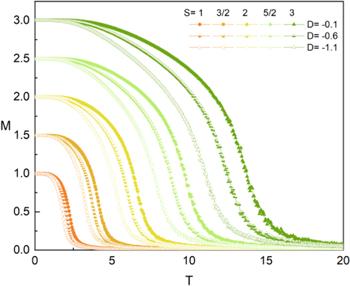

S = 1/2, 1, 3/2, 2, 5/2 and 3) on magnetization, magnetic susceptibility and specific heat of Ising fullerene-like nanostructures was explored. Akıncı

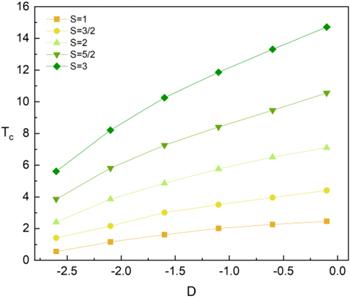

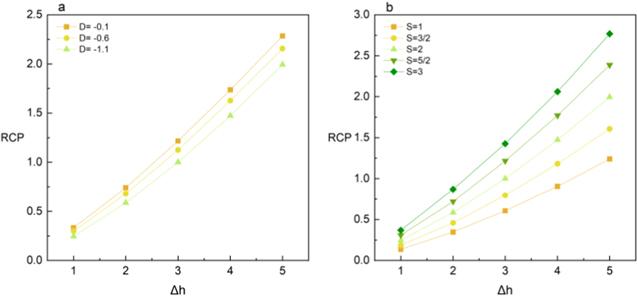

et al investigated the magnetocaloric properties of the spin-

S Ising model on a honeycomb lattice with some spin values of

S = 1, 3/2, 2, 5/2, 3, 7/2 using EFT [

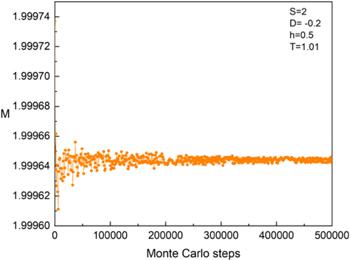

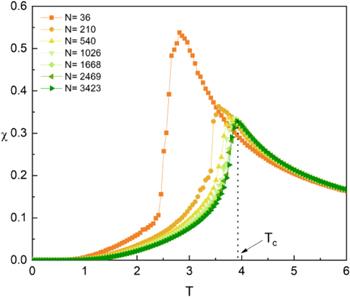

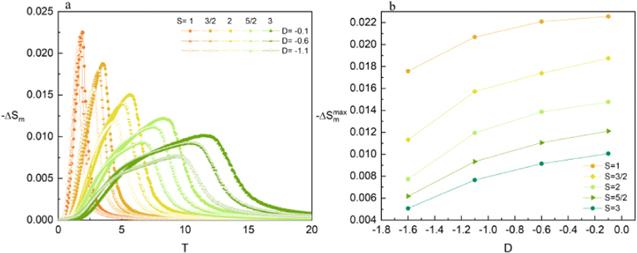

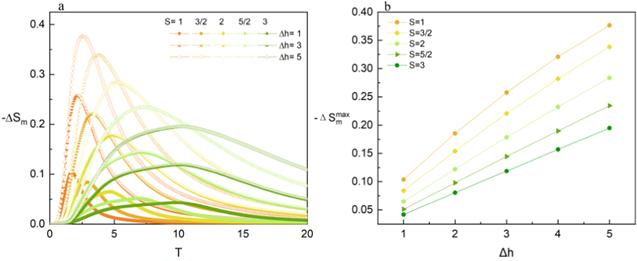

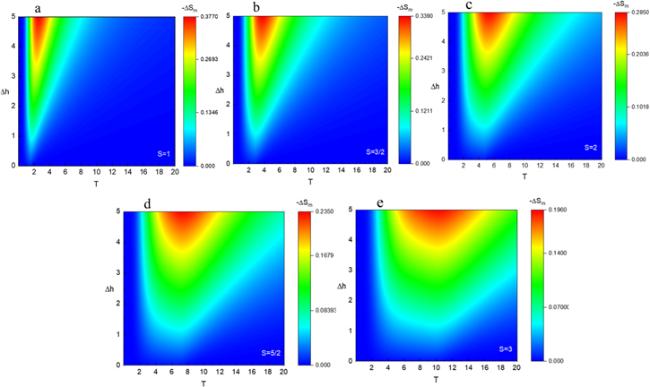

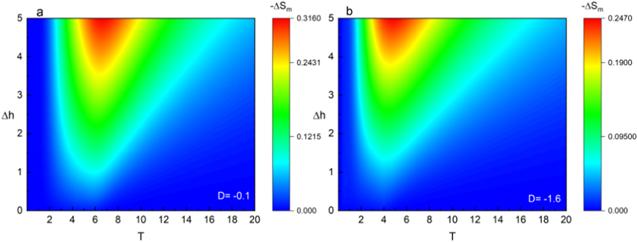

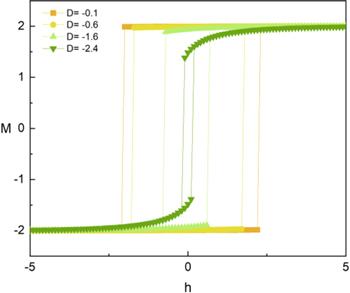

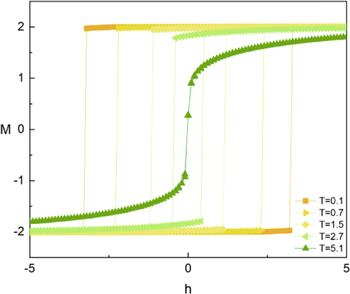

42]. They found that larger spin quantum numbers can improve the cooling capacity and MCE of the system. These research results have motivated us to clarify how changes in spin quantum numbers affect the magnetism, thermodynamics and MCE of borophene monolayers. Hence, in this study, using the Monte Carlo method we explore the influence of crystal field, external magnetic field and spin quantum number on the magnetic characteristics and magnetocaloric effect of borophene structure.