1. Introduction

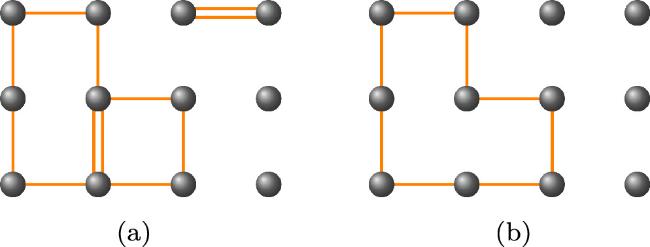

Figure 1. Typical graphical configurations for the Ising model in representation ( |

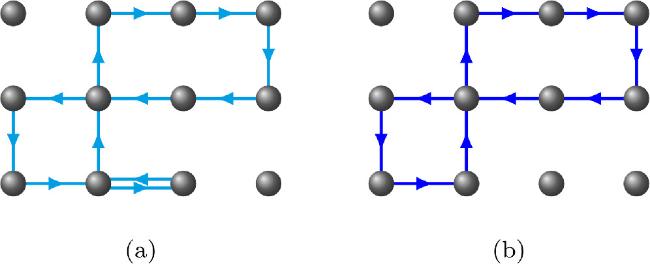

Figure 2. Typical graphical configurations for the 2D XY model in representation ( |

2. Hamiltonian and graphical representations

2.1. N = 1: the Ising model

2.2. N = 2: the XY model

2.3. Arbitrary N

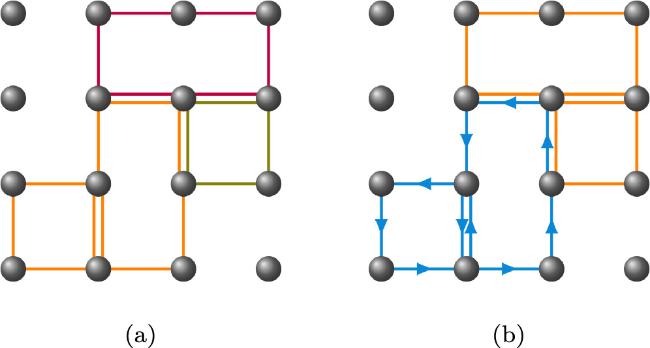

Figure 3. Typical graphical configurations for the O(3) spin model at different ℓ values: (a) For ℓ = 0, the configuration is composed of three copies of the Ising model graphs, as shown by orange, olive, and purple undirected lines, respectively; (b) for ℓ = 1, the configuration includes one copy of the XY model graph, denoted by the cyan directed lines, and an additional copy of the Ising model graph, represented by orange undirected lines. In both instances, each bond or site contributes a weight factor as specified in equations ( |

3. Worm algorithm

Algorithm 1. Worm algorithm for the O(N) spin model |

| if I = M then |

| Randomly choose a site $I^{\prime} $ from all sites in the lattice, and a copy of the subgraphs denoted as $\gamma ^{\prime} $ from ℓ copies of XY graphs and $N-2{\ell }$ copies of Ising graphs. |

| With the acceptance probability ${P}_{\gamma \to \gamma ^{\prime} }^{{acc}}(I\to I^{\prime} )$, set $I^{\prime} $ as the new location of both Ira and Masha, and change current modified subgraph to $\gamma ^{\prime} $, namely set $I=M=I^{\prime} $, $\gamma =\gamma ^{\prime} $. |

| end if |

| if γ is an XY subgraph then |

| Randomly select a site $I^{\prime} $ from all the nearest neighbor sites of site I. |

| If $I\to I^{\prime} $ is along the positive direction we selected in advance, set $\lambda =+1$, otherwise, set $\lambda =-1$. |

| Choose sgn to be + or − with equal probability. |

| Set ${m}_{{II}^{\prime} }^{{sgn}(\gamma )}={m}_{{II}^{\prime} }^{{sgn}(\gamma )}+\lambda \cdot {sgn}$ and move Ira to $I^{\prime} $, namely set $I=I^{\prime} $, with the acceptance probability ${P}_{\gamma ,{xy}}^{{acc}}(I\to I^{\prime} ,{sgn})$, unless this operation makes ${m}_{{II}^{\prime} }^{{sgn}(\gamma )}$ negative and is rejected directly. Here, sgn stands for +1 or −1 in the calculation correspondingly. |

| else |

| Randomly select a site $I^{\prime} $ from all the nearest neighbor sites of site I. |

| Select λ from +1 and −1 with equal probability. |

| Set ${n}_{{II}^{\prime} }^{(\gamma )}={n}_{{II}^{\prime} }^{(\gamma )}+\lambda $ and move Ira to $I^{\prime} $, namely set $I=I^{\prime} $, with the acceptance probability ${P}_{\gamma ,\mathrm{Is}}^{{acc}}(I\to I^{\prime} )$, unless this operation makes ${n}_{{II}^{\prime} }^{(\gamma )}$ negative and is rejected directly. |

| end if |

4. Numerical simulations

4.1. Setup

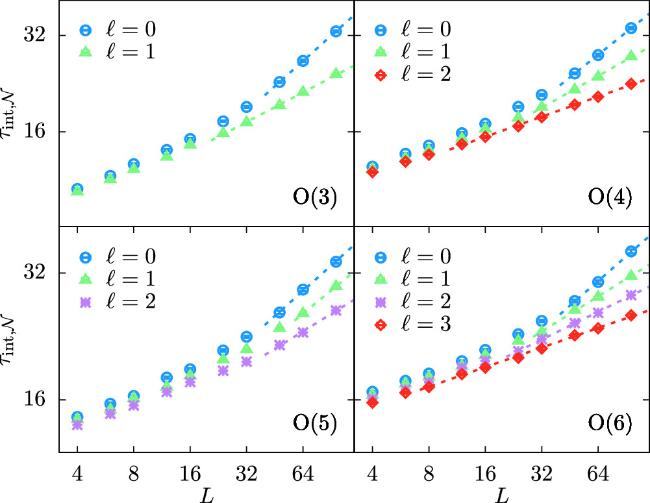

Table 1. Critical couplings Kc we applied to simulate at for each N, and corresponding dynamical critical exponents ${z}_{\mathrm{int},{ \mathcal N }}$ at different ℓ which are roughly estimated via fitting the data by equation ( |

4.2. Results

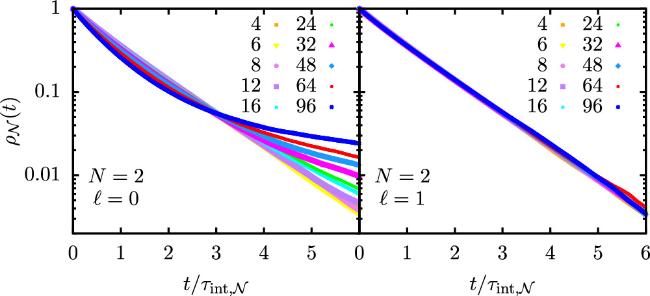

Figure 4. Autocorrelation function ${\rho }_{{ \mathcal N }}(t)$ at criticality versus $t/{\tau }_{\mathrm{int},{ \mathcal N }}$ for N = 2. At ℓ = 1, ${\rho }_{{ \mathcal N }}(t)$ is very close to a pure exponential decay, while at ℓ = 0, it exhibits a crossover from a pure exponential to a complicated behavior as L increases. |

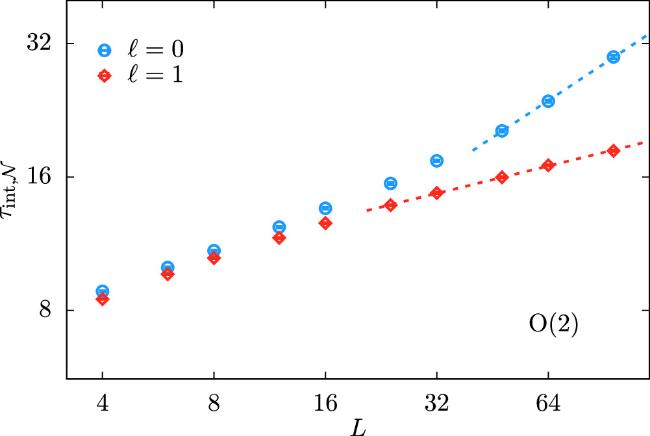

Figure 5. Integrated autocorrelation time ${\tau }_{\mathrm{int},{ \mathcal N }}$ at criticality versus system size L for N = 2. Here, ${\tau }_{\mathrm{int},{ \mathcal N }}$ is in the unit of one system sweep which equals to the number of bonds in the system. Blue and red points are for ℓ = 0 and 1, respectively. Dashed lines show the corresponding fitting results at large L with the fitting formula equation ( |

Figure 6. Integrated autocorrelation time ${\tau }_{\mathrm{int},{ \mathcal N }}$ at criticality for N = 3, 4, 5 and 6 at different ℓ, in the unit of system sweep. Points of different colors represent data for different ℓ, and dashed lines here have the same meaning as those in figure 5. |

5. Discussion

Appendix A. Computation of equation (24 )

Appendix B. Acceptance probabilities

| I | (I)For $(\gamma ,I)\to (\gamma ^{\prime} ,I^{\prime} )$: $\begin{eqnarray}{q}^{(1)}=\displaystyle \frac{{g}_{I}+N}{{g}_{I}^{(\gamma )}+f(\gamma )}\displaystyle \frac{{g}_{I^{\prime} }^{(\gamma ^{\prime} )}+f(\gamma ^{\prime} )}{{g}_{I^{\prime} }+N},\end{eqnarray}$ where $\begin{eqnarray}f(\gamma )=\left\{\begin{array}{cc}2, & \mathrm{if}\ \gamma \ \mathrm{is}\ \mathrm{an}\ \mathrm{XY}\ \mathrm{subgraph}\\ 1, & \mathrm{if}\ \gamma \ \mathrm{is}\ \mathrm{an}\ \mathrm{Ising}\ \mathrm{subgraph}\end{array}\right.,\end{eqnarray}$ $\begin{eqnarray}{g}_{I}^{(\gamma )}=\left\{\begin{array}{cc}{k}_{I}^{(\gamma )}, & \mathrm{if}\,\gamma \,\mathrm{is}\,\mathrm{an}\,\mathrm{XY}\,\mathrm{subgraph}\\ {l}_{I}^{(\gamma )}, & \mathrm{if}\,\gamma \,\mathrm{is}\,\mathrm{an}\,\mathrm{Ising}\,\mathrm{subgraph}\end{array}\right.,\end{eqnarray}$ and ${g}_{I}={\sum }_{\alpha }{k}_{I}^{(\alpha )}+{\sum }_{\beta }{l}_{I}^{(\beta )}$. The expressions of ${k}_{I}^{(\gamma )}$ and ${l}_{I}^{(\gamma )}$ are given by equation ( |

| II | (II)When γ is an XY subgraph: (i)${m}_{{II}^{\prime} }^{{sgn}(\gamma )}\to {m}_{{II}^{\prime} }^{{sgn}(\gamma )}+1$: $\begin{eqnarray}{q}^{(2)}=\displaystyle \frac{K}{2({m}_{{II}^{\prime} }^{{sgn}(\gamma )}+1)}\displaystyle \frac{{h}_{I^{\prime} }^{(\gamma )}+2}{{h}_{I^{\prime} }+N}\end{eqnarray}$ (ii)${m}_{{II}^{\prime} }^{{sgn}(\gamma )}\to {m}_{{II}^{\prime} }^{{sgn}(\gamma )}-1$: $\begin{eqnarray}{q}^{(2)}=\displaystyle \frac{2{m}_{{II}^{\prime} }^{{sgn}(\gamma )}}{K}\displaystyle \frac{{h}_{I}+N-2}{{h}_{I}^{(\gamma )}}.\end{eqnarray}$ |

| III | (III)When γ is an Ising subgraph: (i)${n}_{{II}^{\prime} }^{(\gamma )}\to {n}_{{II}^{\prime} }^{(\gamma )}+1$: $\begin{eqnarray}{q}^{(3)}=\displaystyle \frac{K}{{n}_{{II}^{\prime} }^{(\gamma )}+1}\displaystyle \frac{{h}_{I^{\prime} }^{(\gamma )}+1}{{h}_{I^{\prime} }+N}\end{eqnarray}$ (ii)${n}_{{II}^{\prime} }^{(\gamma )}\to {n}_{{II}^{\prime} }^{(\gamma )}-1$: $\begin{eqnarray}{q}^{(3)}=\displaystyle \frac{{n}_{{II}^{\prime} }^{(\gamma )}}{K}\displaystyle \frac{{h}_{I}+N-2}{{h}_{I}^{(\gamma )}-1}\end{eqnarray}$ |