1. Introduction

1.1. Motivation

1.2. Previous work

| • | In many study of QRT, a resource is not necessarily universal, i.e. not required to enable universal quantum computing. For instance, the QRT of thermodynamics defines athermality [29] which does not aim for computational universality. Here, our study of QRT is for UQCM. A UQCM is a framework to realize any quantum algorithms, and two models are equivalent if tasks or algorithms in them can simulate each other efficiently. The universality requires to consider different types of operational tasks instead of individual ones, as some tasks are special or interchangeable. Therefore, we introduce universal resources to characterize each UQCM. This provides a solid computational scheme to classify quantum resources. |

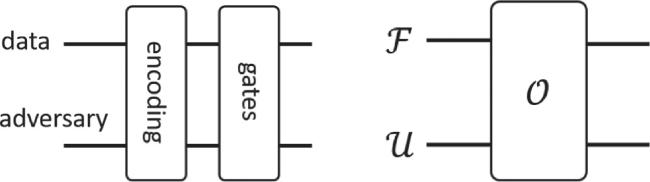

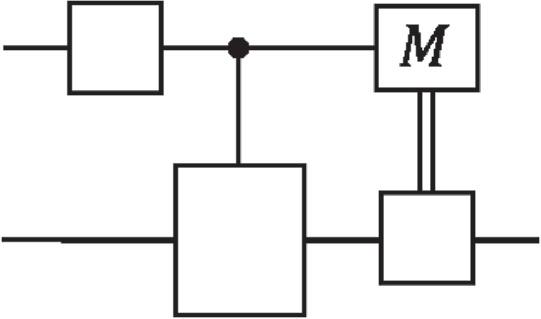

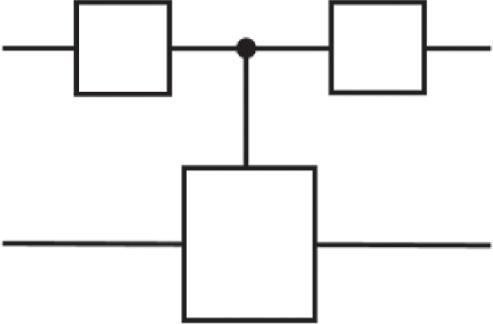

| • | A classification for UQCM was developed [37]. It proposed a table for UQCM with two categories based on a ‘quartet model': with bipartite input structure and bipartite evolution structure. See figure 1 (left). One category is for fault-tolerance, i.e. coding-based models, and one is for universality. In this work, we only study the category for universality, and all the three families we identify belong to this category. Using QRT improves the quartet model: the bipartite input is specified to be free states and universal resources, and the evolution gates is specified to be free operations. Previously, MBQC and adiabatic quantum computing (AQC) [38] were treated as coding-based models since they can be viewed as dynamic coding methods. However, if we only restrict to static coding method, then MBQC and AQC must be treated using other methods. In this work, we find MBQC belongs to the amplitude family, and AQC belongs to the Hamiltonian family. Our classification in this paper is an improvement of the previous one. |

| • | Although in the past MBQC was not studied along with QRT, many studies on this subject are precursors for a resource theory of it. The universality for MBQC was largely explored before the rising of QRT [39, 40], such as the measure of entanglement width. A classical version of MBQC was defined [41]. As was mentioned, highly entangled states are mostly useless for this model [9, 10]. Instead, recently it was found that symmetry-protected topological (SPT) order is resourceful [26-28], and this lays the foundation for our resource theory of MBQC in this work. Quantum contextuality [13, 14, 42-44] has also been investigated for this model [45, 46], but was not claimed to be the universal resource. In this work, we will further analyze the notion of quantum contextuality, and introduce a model directly based on it. |

Figure 1. The ‘quartet model' [37] (left) and resource-theoretic model (right) for universal quantum computing. |

1.3. Summary

| • | We extend resource theory to the setting of universal resources. This finds a place to use resource theory, and draw connections between quantum information and quantum computing. |

| • | We use QRT to study UQCM and introduce families of UQCMs, which stands as a unique approach to unify and classify them, examine their physics, and find new ones. |

| • | We define a universal resource theory for MBQC, and we clarify the relation with contextuality. |

| • | We introduce the models of CQC and PMQC, as generations in the p-family. |

| • | We present a primary resource-theoretic study for Hamiltonian-based models. |

| • | We study the relation between quantum algorithms and resources. This helps to resolve puzzles, inspire ideas for new quantum algorithms. |

Table 1. The abbreviations of models and their full terms. |

| QCM | Quantum circuit model |

| LQTM | Local quantum Turing machine |

| MBQC | Measurement-based quantum computing |

| CQC | Contextual quantum computing |

| MSI | Magic-state injection |

| PMQC | Post-magical quantum computing |

| HQS | Hamiltonian quantum simulation |

| HQCA | Hamiltonian quantum cellular automata |

| AQC | Adiabatic quantum computing |

2. Universal resource

2.1. Resource

| (i) It is zero for free objects; f(ρ = 0), $\forall \rho \in { \mathcal F };$ | |

| (ii) It is positively upper bounded for finite dimensional Hilbert spaces; | |

| (iii) It is asymptotically continuous; f(ρ) → f(σ) whenever ρ → σ, $\forall \rho ,\sigma \in { \mathcal D };$ | |

| (iv) It is subadditive; f(ρ ⨂ σ) ≤ f(ρ) + f(σ), $\forall \rho ,\sigma \in { \mathcal D };$ | |

| (v) It is non-increasing under free operations; f(ρ) ≥ f(Φ(ρ)), $\forall {\rm{\Phi }}\in { \mathcal O }$. |

2.2. Universal resource

2.3. Families of models

Table 2. The triplet of the amplitude family of UQCMs. Details can be found in section |

| QCM | LQTM | MBQC | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ${ \mathcal F }$ | BIT | ⊃ | SEP | ⊃ | PRO |

| ${ \mathcal O }$ | CC | ⊃ | SLOCC | ⊃ | 1O1C |

| ${ \mathcal U }$ | COH | ≺ | EBIT | ≺ | UENT |

Table 3. The triplet of the probability family of UQCMs. Details can be found in section |

| CQC | MSI | PMQC | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ${ \mathcal F }$ | BIT | ⊃ | STAB | ⊃ | 1STAB |

| ${ \mathcal O }$ | CC | ⊃ | CLIF | ⊃ | 1CLIF |

| ${ \mathcal U }$ | CONT | ≺ | MAGIC | ≺ | PMAGIC |

Table 4. The triplet of the Hamiltonian family of UQCMs. Details can be found in section |

| HQS | HQCA | AQC | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ${ \mathcal F }$ | STOQ | ⊃ | BIT | ⊃ | PRO |

| ${ \mathcal O }$ | LINEAR | ⊃ | PARALLEL | ⊃ | GAPPED |

| ${ \mathcal U }$ | NSTOQ | ≺ | COH | ≺ | 1DQW |

3. The a-family

3.1. Quantum circuit model

| i | (i) Initialize at the all-zero state ∣00 ⋯ 0⟩ of qubits; |

| ii | (ii) Apply a sequence of unitary gates; |

| iii | (iii) Readout by measurements in the Pauli Z basis. |

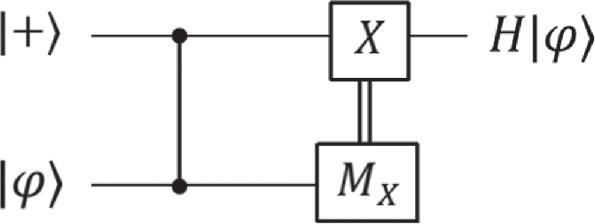

Figure 2. Quantum teleportation of H gate. |

For a quantum channel ${ \mathcal E }$, its classical dual state is defined as

3.2. Local quantum Turing machine

3.3. Measurement-based quantum computing

| i | (i)A universal resource state; |

| ii | (ii)A sequence of on-site adaptive measurements. |

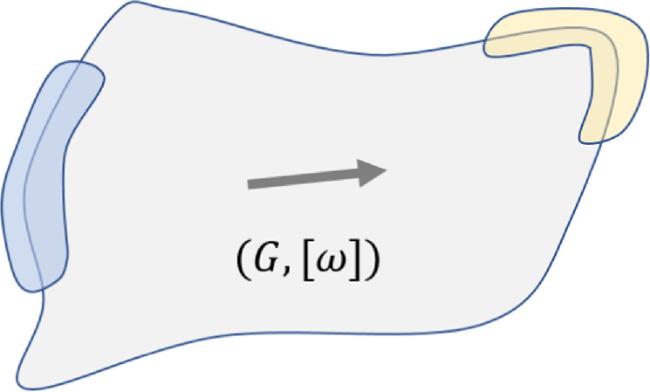

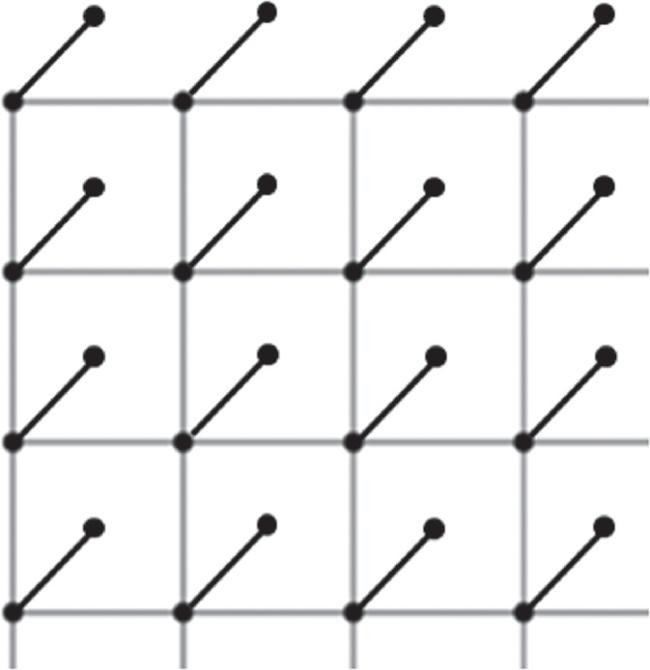

Figure 3. A schematics for the information flow (the arrow) from the input (blue region) to the output (yellow region) of a computation in MBQC that is labelled by (G, [ω]). |

4. The p-family

4.1. Contextual quantum computing

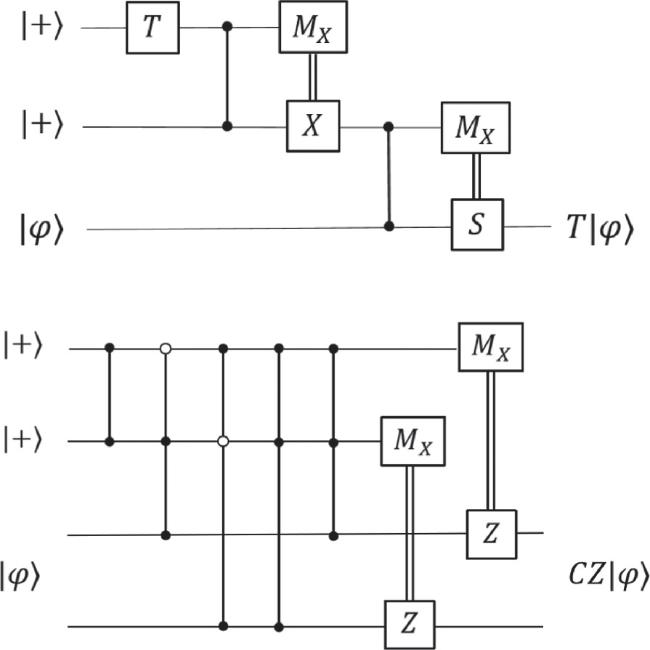

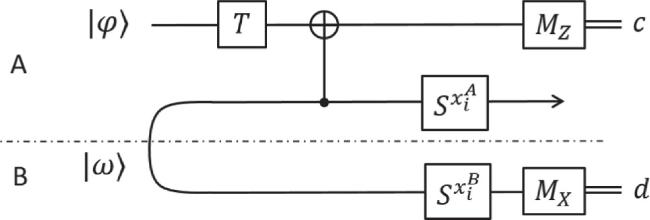

Figure 4. Quantum circuits to realized the T gate (top panel) and CZ gate (bottom panel). |

A contextual quantum circuit contains two registers: one as control, one as data, and it realizes process of the form

Figure 5. A schematics of the contextual quantum circuit in definition |

4.2. Magic-state injection

4.3. Post-magical quantum computing

Figure 6. Broadbent's non-signaling T gate teleportation. The curve is the ebit ∣ω⟩. The middle wire with arrow carries the output. |

Figure 7. A schematics of a tailed cluster state ∣Φ⟩ ( |

5. The h-family

5.1. Hamiltonian quantum simulation

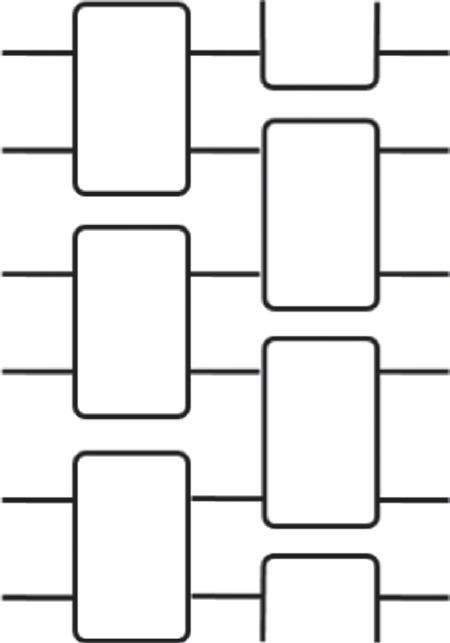

5.2. Hamiltonian quantum cellular automata

Figure 8. The schematics for a QCA brickwork circuit. |

5.3. Adiabatic quantum computing

6.1. Quantum algorithms and resources

Figure 9. A local term in the HQCA model. The back dots are for data qubits, circle for an ancilla qubit, triangle for a program qutrit. |

Figure 10. The schematics of a sandwiched circuit which is a special case of that in figure 5. |