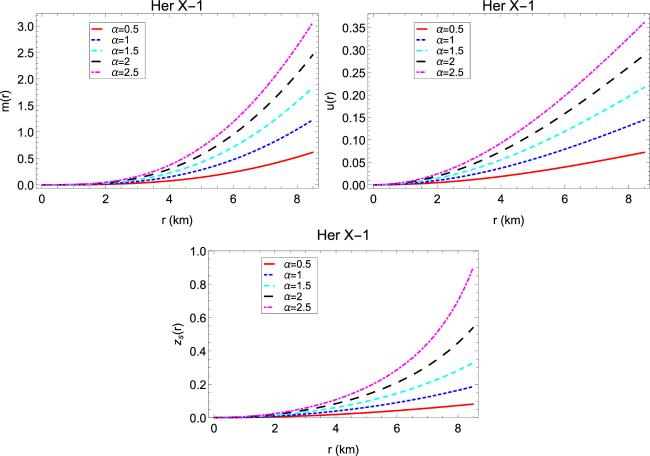

Central density, surface density, central pressure, compactness factor, and surface redshift have been presented for the compact star Her X-1 for different values of α in table

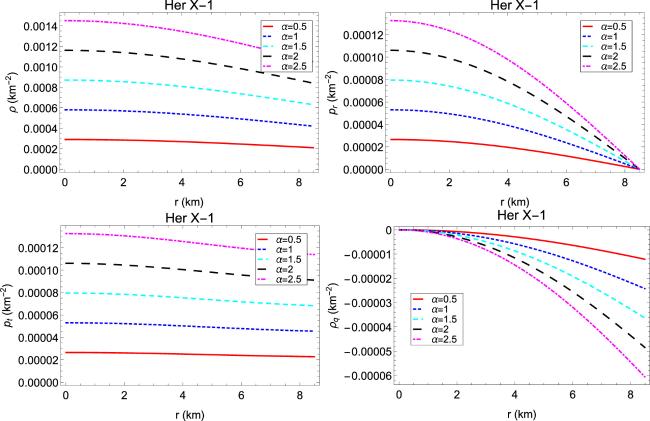

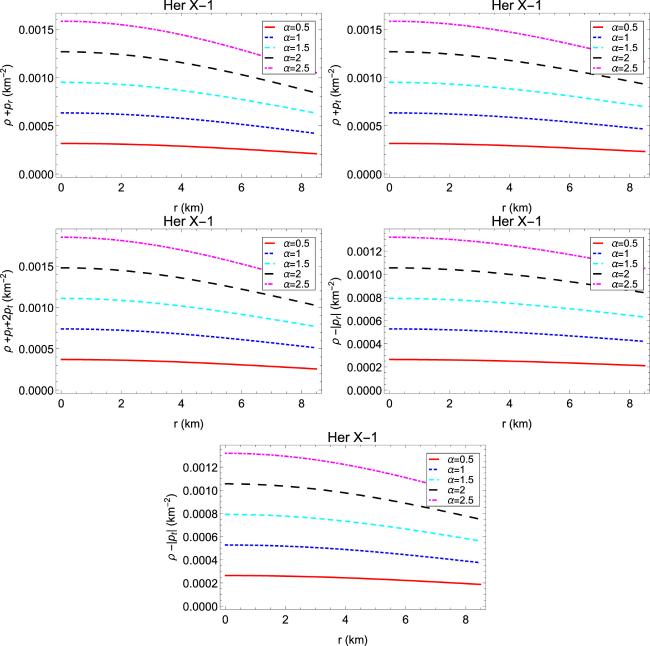

2. According to our findings, all three thermodynamic observables

ρ,

pr, and

pt remain positive and reach their highest values at the core of the compact star. This indicates that they behave monotonically, decreasing from the center to the boundary. It is interesting to see that

ρ,

pr, and

pt have higher central values when

α = 2.5 is applied; however, these values are lower when

α = 0.5. For all chosen values of

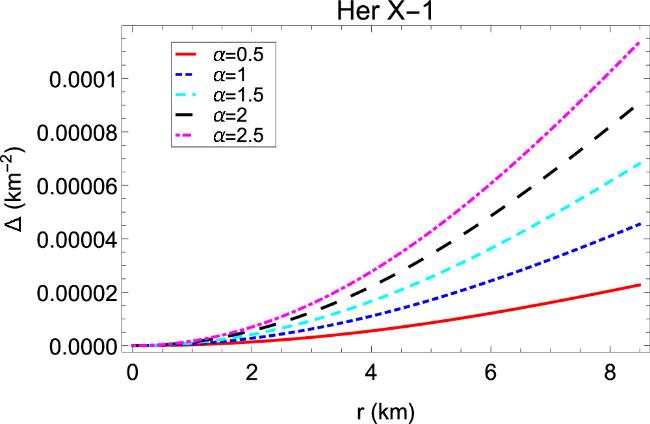

α, the anisotropic factor Δ is a positive and monotonic increasing function throughout the object. In order to prevent point singularities or the creation of a black hole, a positive anisotropy factor signifies that the system is subject to an external repulsive force that works to balance the gravitational attraction. For all values of

α, in this investigation, the energy conditions are valid. Since the material inside the object cannot travel faster than light, our current model satisfies the constraints of causality. The profiles of

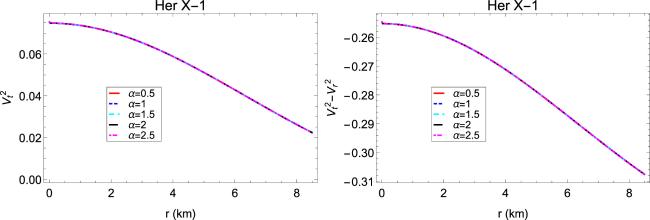

Vt2 coincide for all values of

α, as seen in figure

7. It has been discovered that the range [0, 1] encompasses the difference between the squares of the subliminal sound speeds, i.e.

$| {V}_{t}^{2}-{V}_{r}^{2}| \in [0,1]$. Figure

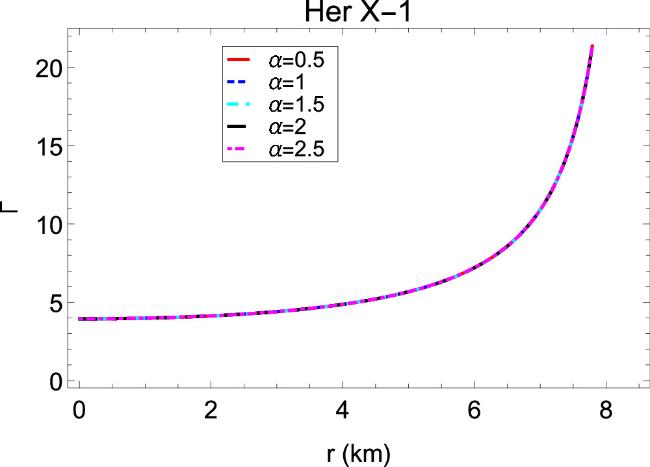

10 illustrates the maximum feasible value of the surface redshift, which cannot be arbitrarily large. The compactness factor for our current model is below the maximum value found in the literature, i.e.

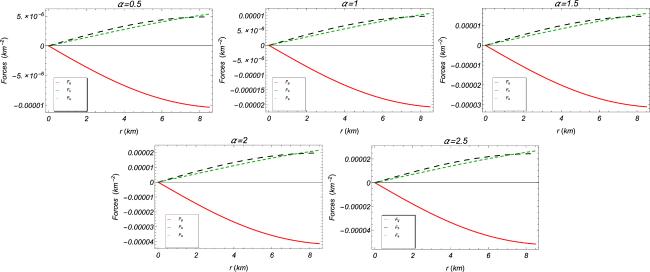

$u{| }_{\max }\lt 4/9$. The TOV equation is used to study the analysis of the balance mechanism in the context of the

f(

T) model. It is demonstrated that the system is subject to three forces for the specific choice of the

f(

T) model, namely the hydrostatic force

Fh, gravitational force

Fg, and anisotropic force

Fa, achieving the equilibrium condition by maintaining the sum of all the forces to be zero. Additionally, we have shown the equation of the state parameters

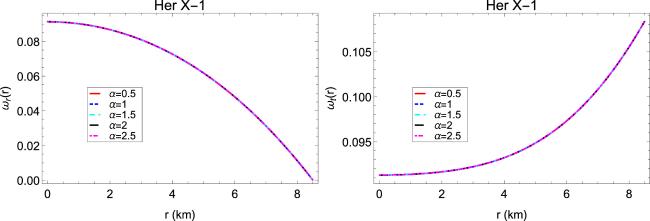

ωr and

ωt for all values of

α, and for our current model, the profiles of

ωr and

ωt coincide for all values of

α. It should be mentioned that

ωr and

ωt both fall within the range [0, 1]. For our current model, the maximum permissible mass and associated radius were determined using the

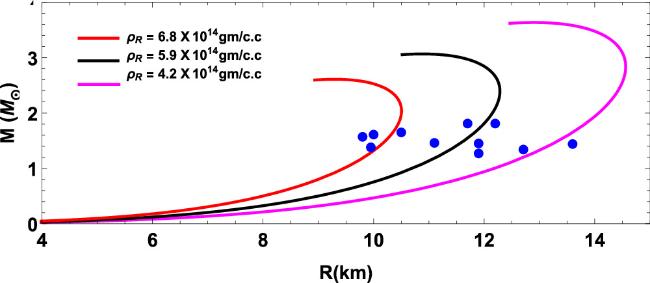

M−

R curve, and they are shown in figure

11. A comprehensive graphical analysis is used to support each of the concepts shown in figures

1–

11. In conclusion, the models we have described here meet all the physical requirements, making them perfect choices to represent reliable models in the context of

f(

T) gravity.