1. Introduction

2. Theoretical method

Table 1. The calculated single-particle levels near the Fermi surface at β2 = 0.30, γ = 0° and β4 = 0.00 for protons and neutrons in the selected nucleus ${}_{60}^{152}$Nd92, together with their wave-function components expanded in the cylindrical basis ∣NnzΛΩ⟩ and spherical basis ∣NljΩ⟩. The calculations are performed using the WS Hamiltonian with the cranking parameters [47, 56]. The proton and neutron Fermi levels correspond to the energies −9.89 MeV and −6.37 MeV, respectively. |

| ϵ(MeV) | The former six main components in terms of ∣NnzΛΩ⟩ (upper) and ∣NljΩ⟩ (lower) | |

|---|---|---|

| Proton | −11.15 | 67.3% $| 420\tfrac{1}{2}\rangle $ + 8.9% $| 440\tfrac{1}{2}\rangle $ + 7.6% $| 431\tfrac{1}{2}\rangle $ + 4.6% $| 220\tfrac{1}{2}\rangle $ + 3.0% $| 411\tfrac{1}{2}\rangle $ + 2.4% $| 400\tfrac{1}{2}\rangle $ |

| 28.9% $| 4{d}_{5/2}\tfrac{1}{2}\rangle $ + 19.7% $| 4{g}_{7/2}\tfrac{1}{2}\rangle $ + 17.1% $| 4{s}_{1/2}\tfrac{1}{2}\rangle $ + 14.6% $| 4{g}_{9/2}\tfrac{1}{2}\rangle $ + 5.8% $| 2{s}_{1/2}\tfrac{1}{2}\rangle $ + 3.5% $| 6{d}_{5/2}\tfrac{1}{2}\rangle $ | ||

| −10.58 | 33.9% $| 550\tfrac{1}{2}\rangle $ + 28.3% $| 541\tfrac{1}{2}\rangle $ + 24.6% $| 530\tfrac{1}{2}\rangle $ + 6.7% $| 521\tfrac{1}{2}\rangle $ + 1.5% $| 510\tfrac{1}{2}\rangle $ + 1.1% $| 330\tfrac{1}{2}\rangle $ | |

| 58.4% $| 5{h}_{11/2}\tfrac{1}{2}\rangle $ + 15.2% $| 5{f}_{7/2}\tfrac{1}{2}\rangle $ + 10.7% $| 3{f}_{7/2}\tfrac{1}{2}\rangle $ + 4.9% $| 7{j}_{15/2}\tfrac{1}{2}\rangle $ + 3.6% $| 7{h}_{11/2}\tfrac{1}{2}\rangle $ + 3.1% $| 7{f}_{7/2}\tfrac{1}{2}\rangle $ | ||

| −10.37 | 98.6% $| 404\tfrac{9}{2}\rangle $ + 0.6% $| 624\tfrac{9}{2}\rangle $ + 0.5% $| 804\tfrac{9}{2}\rangle $ + 0.3% $| 604\tfrac{9}{2}\rangle $ + 0.1% $| 824\tfrac{9}{2}\rangle $ + 0.0% $| 844\tfrac{9}{2}\rangle $ | |

| 97.1% $| 4{g}_{9/2}\tfrac{9}{2}\rangle $ + 1.8% $| 6{i}_{13/2}\tfrac{9}{2}\rangle $ + 0.5% $| 6{i}_{11/2}\tfrac{9}{2}\rangle $ + 0.3% $| 8{g}_{9/2}\tfrac{9}{2}\rangle $ + 0.2% $| 10{g}_{9/2}\tfrac{9}{2}\rangle $ + 0.0% $| 6{g}_{9/2}\tfrac{9}{2}\rangle $ | ||

| −9.89 | 60.6% $| 541\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 19.4% $| 532\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 14.2% $| 521\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 1.6% $| 512\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 1.4% $| 321\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 0.7% $| 981\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ | |

| 64.9% $| 5{h}_{11/2}\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 13.0% $| 5{f}_{7/2}\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 8.8% $| 3{f}_{7/2}\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 5.0% $| 7{j}_{15/2}\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 2.9% $| 7{h}_{11/2}\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 2.0% $| 7{f}_{7/2}\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ | ||

| −8.63 | 90.5% $| 413\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 7.6% $| 422\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 0.5% $| 402\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 0.4% $| 202\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 0.4% $| 633\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 0.1% $| 813\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ | |

| 85.6% $| 4{g}_{7/2}\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 6.0% $| 4{g}_{9/2}\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 3.7% $| 6{i}_{11/2}\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 3.0% $| 4{d}_{5/2}\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 0.6% $| 2{d}_{5/2}\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 0.6% $| 6{i}_{13/2}\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ | ||

| −8.61 | 78.3% $| 532\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 12.2% $| 523\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 6.3% $| 512\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 1.2% $| 312\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 0.6% $| 752\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 0.5% $| 972\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ | |

| 74.5% $| 5{h}_{11/2}\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 8.9% $| 5{f}_{7/2}\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 5.7% $| 3{f}_{7/2}\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 5.0% $| 7{j}_{15/2}\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 1.9% $| 5{h}_{9/2}\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 1.6% $| 7{h}_{11/2}\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ | ||

| −8.16 | 83.1% $| 411\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 4.4% $| 211\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 3.5% $| 431\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 3.2% $| 422\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 2.0% $| 631\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 1.7% $| 402\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ | |

| 63.6% $| 4{d}_{5/2}\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 12.8% $| 4{g}_{7/2}\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 10.1% $| 4{g}_{9/2}\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 3.3% $| 4{d}_{3/2}\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 3.2% $| 2{d}_{5/2}\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 2.3% $| 6{d}_{5/2}\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ | ||

| Neutron | −7.31 | 83.2% $| 402\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 5.6% $| 602\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 5.1% $| 202\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 3.0% $| 411\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 2.0% $| 622\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 0.5% $| 422\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ |

| 74.2% $| 4{d}_{3/2}\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 8.9% $| 4{g}_{7/2}\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 7.4% $| 4{d}_{5/2}\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 3.6% $| 6{d}_{3/2}\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 2.2% $| 2{d}_{3/2}\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 0.7% $| 4{g}_{9/2}\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ | ||

| −6.94 | 27.0% $| 640\tfrac{1}{2}\rangle $ + 26.1% $| 651\tfrac{1}{2}\rangle $ + 24.0% $| 660\tfrac{1}{2}\rangle $ + 10.7% $| 631\tfrac{1}{2}\rangle $ + 3.2% $| 620\tfrac{1}{2}\rangle $ + 2.0% $| 880\tfrac{1}{2}\rangle $ | |

| 51.1% $| 6{i}_{13/2}\tfrac{1}{2}\rangle $ + 12.7% $| 6{g}_{9/2}\tfrac{1}{2}\rangle $ + 12.5% $| 4{g}_{9/2}\tfrac{1}{2}\rangle $ + 7.8% $| 8{i}_{13/2}\tfrac{1}{2}\rangle $ + 6.0% $| 8{g}_{9/2}\tfrac{1}{2}\rangle $ + 4.3% $| 8{k}_{17/2}\tfrac{1}{2}\rangle $ | ||

| −6.45 | 46.9% $| 651\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 22.0% $| 642\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 19.2% $| 631\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 3.5% $| 622\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 2.6% $| 871\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 1.3% $| 431\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ | |

| 56.3% $| 6{i}_{13/2}\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 11.7% $| 6{g}_{9/2}\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 11.2% $| 4{g}_{9/2}\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 7.4% $| 8{i}_{13/2}\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 4.8% $| 8{g}_{9/2}\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 4.5% $| 8{k}_{17/2}\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ | ||

| −6.37 | 96.2% $| 505\tfrac{11}{2}\rangle $ + 2.9% $| 705\tfrac{11}{2}\rangle $ + 0.8% $| 725\tfrac{11}{2}\rangle $ + 0.1% $| 905\tfrac{11}{2}\rangle $ + 0.0% $| 716\tfrac{11}{2}\rangle $ + 0.0% $| 925\tfrac{11}{2}\rangle $ | |

| 96.9% $| 5{h}_{11/2}\tfrac{11}{2}\rangle $ + 1.4% $| 7{j}_{15/2}\tfrac{11}{2}\rangle $ + 0.9% $| 7{h}_{11/2}\tfrac{11}{2}\rangle $ + 0.4% $| 7{j}_{13/2}\tfrac{11}{2}\rangle $ + 0.3% $| 11{h}_{11/2}\tfrac{11}{2}\rangle $ + 0.1% $| 9{h}_{11/2}\tfrac{11}{2}\rangle $ | ||

| −6.20 | 60.0% $| 521\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 20.1% $| 532\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 4.0% $| 741\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 3.8% $| 321\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 2.6% $| 512\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 2.3% $| 721\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ | |

| 32.8% $| 5{f}_{7/2}\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 28.2% $| 5{h}_{9/2}\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 9.1% $| 5{h}_{11/2}\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 7.3% $| 7{f}_{7/2}\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 7.1% $| 5{p}_{3/2}\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 3.1% $| 3{p}_{3/2}\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ | ||

| −5.55 | 65.4% $| 642\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 16.3% $| 633\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 11.0% $| 622\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 2.6% $| 862\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 1.2% $| 422\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 1.1% $| 613\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ | |

| 52.5% $| 5{h}_{9/2}\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 14.9% $| 5{f}_{7/2}\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 9.5% $| 5{f}_{5/2}\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 9.4% $| 5{h}_{11/2}\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 2.9% $| 3{f}_{5/2}\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 2.6% $| 7{j}_{13/2}\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ | ||

| −5.54 | 67.4% $| 523\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 16.0% $| 532\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 8.2% $| 512\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 2.8% $| 312\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 1.8% $| 503\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 1.2% $| 712\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ | |

| 64.8% $| 6{i}_{13/2}\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 9.7% $| 6{g}_{9/2}\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 8.6% $| 4{g}_{9/2}\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 6.5% $| 8{i}_{13/2}\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 4.6% $| 8{k}_{17/2}\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 3.0% $| 8{g}_{9/2}\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ |

Table 2. The same as table 1, but β4 = 0.10 and the proton and neutron Fermi levels correspond to the energies −10.50 MeV and −6.89 MeV, respectively. |

| ϵ (MeV) | The former six main components in terms of ∣NnzΛΩ⟩ (upper) and ∣NljΩ⟩ (lower) | |

|---|---|---|

| Proton | −10.99 | 82.9% $| 422\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 10.6% $| 431\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 4.1% $| 402\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 0.8% $| 211\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 0.4% $| 411\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 0.3% $| 842\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ |

| 67.9% $| 4{g}_{7/2}\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 13.9% $| 4{g}_{9/2}\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 6.3% $| 4{d}_{3/2}\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 4.7% $| 6{i}_{11/2}\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 2.5% $| 4{d}_{5/2}\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 1.7% $| 2{d}_{3/2}\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ | ||

| −10.87 | 98.4% $| 404\tfrac{9}{2}\rangle $ + 0.9% $| 604\tfrac{9}{2}\rangle $ + 0.4% $| 804\tfrac{9}{2}\rangle $ + 0.2% $| 824\tfrac{9}{2}\rangle $ + 0.0% $| 624\tfrac{9}{2}\rangle $ + 0.0% $| 1044\tfrac{9}{2}\rangle $ | |

| 99.0% $| 4{g}_{9/2}\tfrac{9}{2}\rangle $ + 0.4% $| 8{g}_{9/2}\tfrac{9}{2}\rangle $ + 0.3% $| 6{i}_{13/2}\tfrac{9}{2}\rangle $ + 0.2% $| 10{g}_{9/2}\tfrac{9}{2}\rangle $ + 0.1% $| 6{i}_{11/2}\tfrac{9}{2}\rangle $ + 0.0% $| 8{k}_{17/2}\tfrac{9}{2}\rangle $ | ||

| −10.66 | 73.3% $| 420\tfrac{1}{2}\rangle $ + 6.0% $| 431\tfrac{1}{2}\rangle $ + 5.3% $| 400\tfrac{1}{2}\rangle $ + 4.8% $| 440\tfrac{1}{2}\rangle $ + 2.9% $| 220\tfrac{1}{2}\rangle $ + 2.5% $| 411\tfrac{1}{2}\rangle $ | |

| 26.0% $| 4{d}_{5/2}\tfrac{1}{2}\rangle $ + 24.5% $| 4{g}_{7/2}\tfrac{1}{2}\rangle $ + 22.5% $| 4{g}_{9/2}\tfrac{1}{2}\rangle $ + 11.2% $| 4{s}_{1/2}\tfrac{1}{2}\rangle $ + 3.5% $| 6{d}_{5/2}\tfrac{1}{2}\rangle $ + 2.3% $| 2{s}_{1/2}\tfrac{1}{2}\rangle $ | ||

| −10.50 | 66.2% $| 541\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 12.7% $| 532\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 12.2% $| 521\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 3.4% $| 321\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 1.8% $| 761\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 1.3% $| 512\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ | |

| 55.0% $| 5{h}_{11/2}\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 12.2% $| 5{f}_{7/2}\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 7.9% $| 3{f}_{7/2}\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 6.5% $| 7{j}_{15/2}\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 4.3% $| 3{p}_{3/2}\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 3.9% $| 7{h}_{11/2}\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ | ||

| −8.30 | 80.9% $| 532\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 8.8% $| 523\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 7.6% $| 512\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 0.7% $| 752\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 0.6% $| 312\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 0.5% $| 952\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ | |

| 73.9% $| 5{h}_{11/2}\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 7.3% $| 5{f}_{7/2}\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 5.8% $| 7{j}_{15/2}\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 4.0% $| 3{f}_{7/2}\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 3.1% $| 5{h}_{9/2}\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 1.5% $| 7{h}_{11/2}\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ | ||

| −7.39 | 90.6% $| 413\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 7.3% $| 422\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 1.0% $| 402\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 0.2% $| 202\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 0.2% $| 833\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 0.2% $| 602\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ | |

| 84.8% $| 4{g}_{7/2}\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 7.5% $| 4{g}_{9/2}\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 4.0% $| 4{d}_{5/2}\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 2.5% $| 6{i}_{11/2}\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 0.4% $| 2{d}_{5/2}\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 0.2% $| 8{k}_{15/2}\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ | ||

| −7.23 | 80.9% $| 411\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 3.8% $| 422\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 3.4% $| 211\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 3.3% $| 402\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 3.3% $| 431\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 2.7% $| 651\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ | |

| 64.0% $| 4{d}_{5/2}\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 12.9% $| 4{g}_{7/2}\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 12.6% $| 4{g}_{9/2}\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 2.2% $| 2{d}_{5/2}\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 2.1% $| 6{g}_{9/2}\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 1.9% $| 6{d}_{5/2}\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ | ||

| Neutron | −7.72 | 73.0% $| 402\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 7.1% $| 602\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 5.7% $| 411\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 5.6% $| 202\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 2.3% $| 642\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 1.9% $| 651\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ |

| 78.2% $| 4{d}_{3/2}\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 6.4% $| 4{g}_{7/2}\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 3.6% $| 6{d}_{3/2}\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 3.0% $| 4{d}_{5/2}\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 2.9% $| 2{d}_{3/2}\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 2.5% $| 6{i}_{13/2}\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ | ||

| −7.64 | 62.5% $| 532\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 18.9% $| 541\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 7.4% $| 512\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 3.7% $| 521\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 3.0% $| 321\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 1.2% $| 752\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ | |

| 39.0% $| 5{h}_{9/2}\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 17.5% $| 5{h}_{11/2}\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 15.1% $| 5{f}_{5/2}\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 5.3% $| 3{f}_{5/2}\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 5.2% $| 5{f}_{7/2}\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 3.9% $| 7{h}_{9/2}\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ | ||

| −7.22 | 51.3% $| 651\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 15.0% $| 631\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 14.0% $| 642\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 5.0% $| 871\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 4.8% $| 402\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 3.5% $| 431\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ | |

| 43.0% $| 6{i}_{13/2}\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 10.5% $| 6{g}_{9/2}\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 9.3% $| 4{g}_{9/2}\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 8.0% $| 8{i}_{13/2}\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 7.6% $| 4{d}_{5/2}\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 5.7% $| 8{g}_{9/2}\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ | ||

| −6.89 | 95.4% $| 505\tfrac{11}{2}\rangle $ + 4.5% $| 705\tfrac{11}{2}\rangle $ + 0.1% $| 925\tfrac{11}{2}\rangle $ + 0.0% $| 905\tfrac{11}{2}\rangle $ + 0.0% $| 725\tfrac{11}{2}\rangle $ + 0.0% $| 716\tfrac{11}{2}\rangle $ | |

| 98.3% $| 5{h}_{11/2}\tfrac{11}{2}\rangle $ + 1.1% $| 7{h}_{11/2}\tfrac{11}{2}\rangle $ + 0.2% $| 11{h}_{11/2}\tfrac{11}{2}\rangle $ + 0.2% $| 7{j}_{15/2}\tfrac{11}{2}\rangle $ + 0.1% $| 9{h}_{11/2}\tfrac{11}{2}\rangle $ + 0.0% $| 7{j}_{13/2}\tfrac{11}{2}\rangle $ | ||

| −5.62 | 69.0% $| 642\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 12.1% $| 633\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 11.0% $| 622\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 3.6% $| 862\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 1.9% $| 422\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 1.1% $| 613\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ | |

| 60.7% $| 6{i}_{13/2}\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 9.0% $| 6{g}_{9/2}\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 7.1% $| 4{g}_{9/2}\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 6.7% $| 8{i}_{13/2}\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 5.7% $| 8{k}_{17/2}\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 3.0% $| 8{g}_{9/2}\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ | ||

| −5.50 | 63.4% $| 521\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 16.0% $| 532\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 3.7% $| 501\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 3.0% $| 321\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 2.6% $| 512\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 2.5% $| 721\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ | |

| 36.2% $| 5{f}_{7/2}\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 26.6% $| 5{h}_{9/2}\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 13.2% $| 5{h}_{11/2}\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 7.9% $| 7{f}_{7/2}\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 4.9% $| 5{p}_{3/2}\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ + 2.4% $| 3{f}_{7/2}\tfrac{3}{2}\rangle $ | ||

| −4.52 | 61.9% $| 523\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 13.9% $| 532\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 12.5% $| 512\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 5.2% $| 503\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 2.5% $| 312\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 2.0% $| 712\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ | |

| 47.2% $| 5{h}_{9/2}\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 22.2% $| 5{f}_{7/2}\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 14.8% $| 5{h}_{11/2}\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 4.9% $| 5{f}_{5/2}\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 2.5% $| 7{j}_{13/2}\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ + 2.4% $| 7{f}_{7/2}\tfrac{5}{2}\rangle $ |

3. Results and discussion

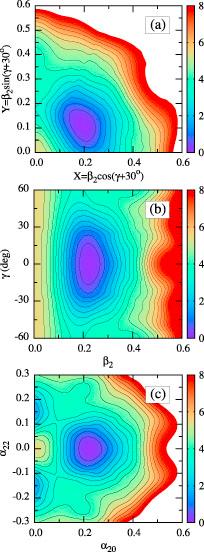

Figure 1. Illustrations of calculated two-dimensional energy surfaces, with contour-line separations of 0.5 MeV, based on quadrupole (or generalized quadrupole)-deformation coordinates (X, Y) (a), (β2, γ) (b) and (α20, α22) (c) planes in Cartesian coordinate systems for the selected nucleus ${}_{60}^{152}$Nd192. Note that the energy has already been subtracted from the minimum value (the same value in each subplot). Let us note that, in (a), (b) and (c), the equilibrium deformations (X = 0.20; Y = 0.12), (β2 = 0.22; γ = 0°) and (α20 = 0.22; α22 = 0.00) are equivalent, as expected. See the text for more details. |

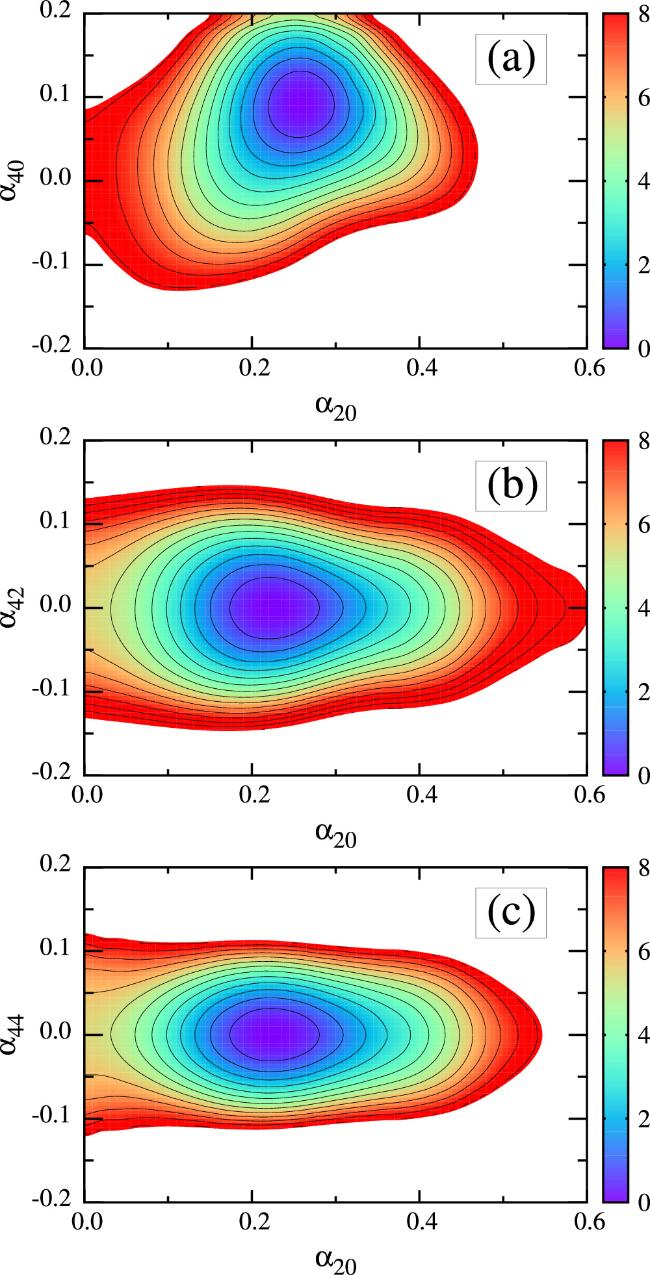

Figure 2. Similar to the preceding illustration in figure 1, but based on quadrupole and hexadecapole-deformation degrees of freedom (α20, α40) (a), (α20, α42) (b) and (α20, α44) (c) for ${}_{60}^{152}$Nd92. |

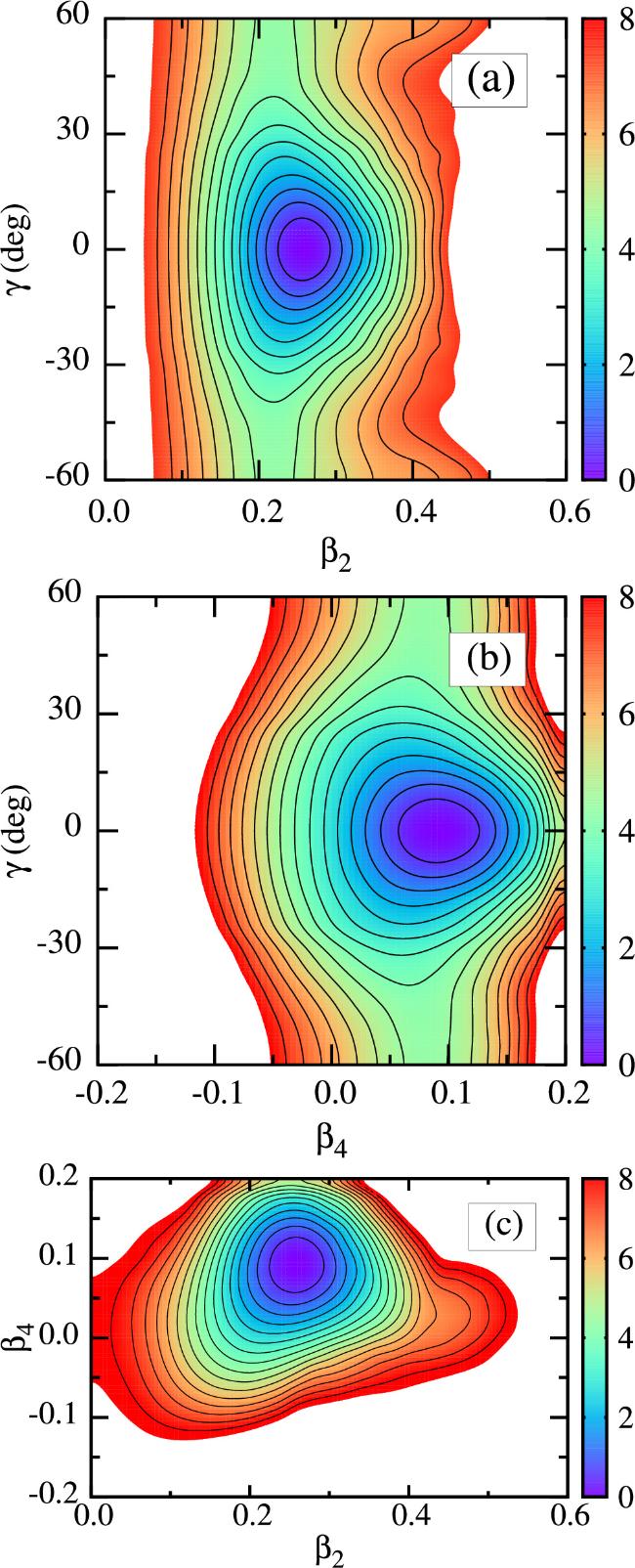

Figure 3. Projections of total energy on the (β2,γ) (a), (β4,γ) (b) and (β2,β4) (c) planes, minimized respectively at each deformation point over the remaining deformations, β4, β2 and γ. Note that the total energy is calculated in the three-dimensional deformation space (β2,γ, β4), and normalization is specified by setting the energy equal to zero at the minimum position. |

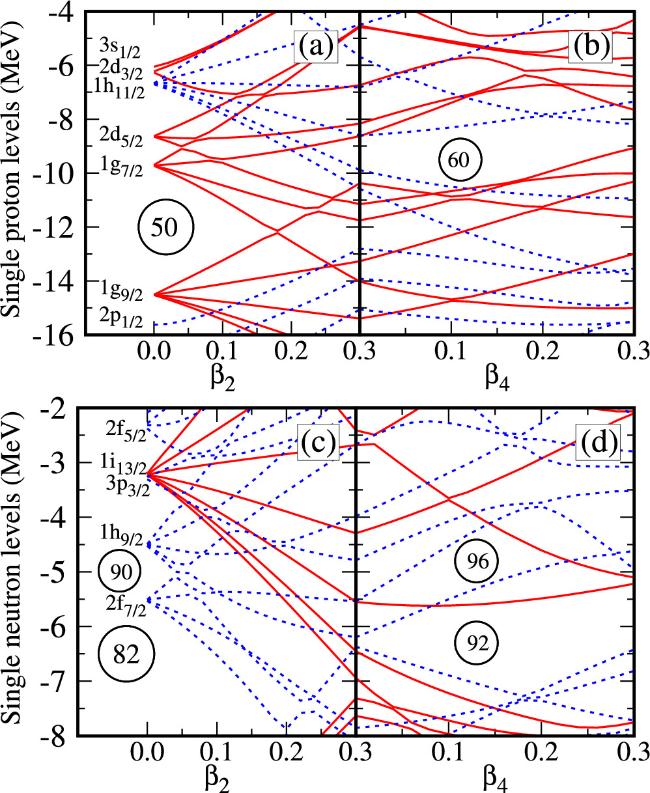

Figure 4. Calculated proton (top) and neutron (bottom) single-particle energies (in the window of interest) as functions of the quadrupole deformation β2 (left) and hexadecapole deformation β4 for ${}_{60}^{152}$Nd92, focusing on the domain near the Fermi surface. Red solid (blue dotted) lines refer to positive and negative parity. The single-particle orbitals at β2=0.0 are labelled by the spherical quantum numbers nlj; for further details, e.g. see tables 1 and 2. |

Table 3. The calculated (Cal.) equilibrium deformation parameters β2 and β4 at ground states for even–even nuclei 148−152Ce, 150−154Nd and 152−156Sm, together with the FY+FRDM (FF) [15], HFBCS [66], and ETFSI [67] calculations and partial experimental (Exp.) β2 values [64] for comparison. |

| Nuclei | β2 | β4 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cal.1a | Cal.2 | FF | HFBCS | ETFSI | Exp. | Cal.1 | Cal.2 | FF | HFBCS | ETFSI | |

| ${}_{58}^{148}$Ce90 | 0.212 | 0.209 | 0.216 | 0.22 | 0.24 | 0.255 | 0.076 | 0.067 | 0.109 | 0.02 | 0.06 |

| ${}_{58}^{150}$Ce92 | 0.242 | 0.235 | 0.252 | 0.25 | 0.26 | 0.317 | 0.092 | 0.082 | 0.126 | 0.02 | 0.07 |

| ${}_{58}^{152}$Ce94 | 0.255 | 0.251 | 0.261 | 0.27 | 0.28 | 0.429 | 0.086 | 0.079 | 0.111 | 0.02 | 0.06 |

| ${}_{60}^{150}$Nd90 | 0.240 | 0.235 | 0.243 | 0.25 | 0.26 | 0.283 | 0.085 | 0.076 | 0.107 | 0.02 | 0.07 |

| ${}_{60}^{152}$Nd92 | 0.262 | 0.256 | 0.262 | 0.27 | 0.29 | 0.348 | 0.095 | 0.085 | 0.128 | 0.02 | 0.07 |

| ${}_{60}^{154}$Nd94 | 0.271 | 0.268 | 0.270 | 0.29 | 0.29 | 0.258 | 0.085 | 0.080 | 0.114 | 0.02 | 0.07 |

| ${}_{62}^{152}$Sm90 | 0.242 | 0.238 | 0.243 | 0.23 | 0.26 | 0.306 | 0.071 | 0.066 | 0.090 | 0.01 | 0.05 |

| ${}_{62}^{154}$Sm92 | 0.266 | 0.262 | 0.270 | 0.27 | 0.28 | 0.340 | 0.081 | 0.074 | 0.113 | 0.01 | 0.06 |

| ${}_{62}^{156}$Sm94 | 0.276 | 0.274 | 0.279 | 0.29 | 0.30 | — | 0.077 | 0.071 | 0.098 | 0.01 | 0.05 |

aCal.1 and Cal.2 respectively indicate that the corresponding deformation parameters are calculated using the cranking and universal WS parameter sets. |

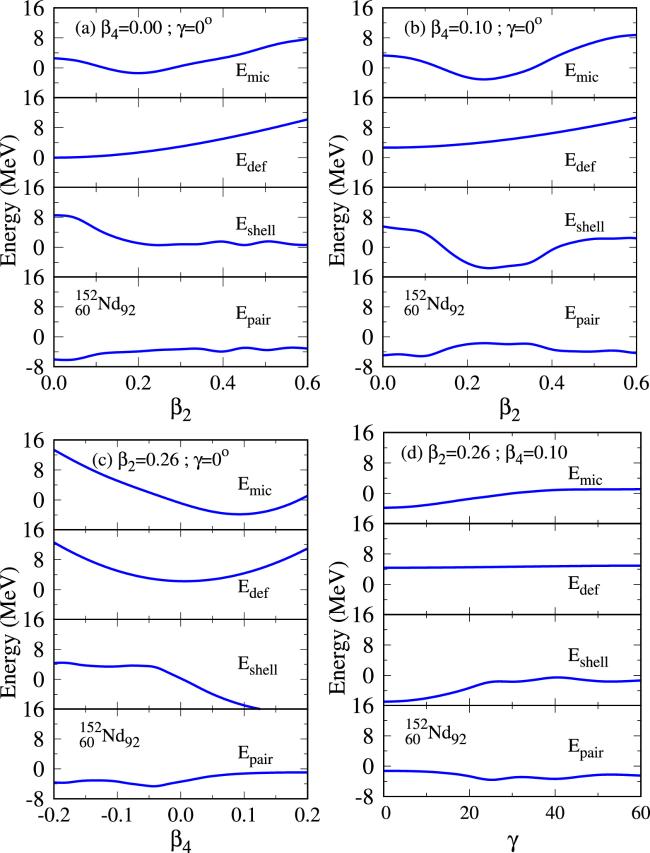

Figure 5. Calculated microscopic energies Emic, following the definition in [15, 41], in functions of different deformation degrees of freedom, together with their deformation energy Edef, quantum shell correction Eshell and pairing-energy contribution Epair, for the selected nucleus ${}_{60}^{152}$Nd92; see the text for further comments. |

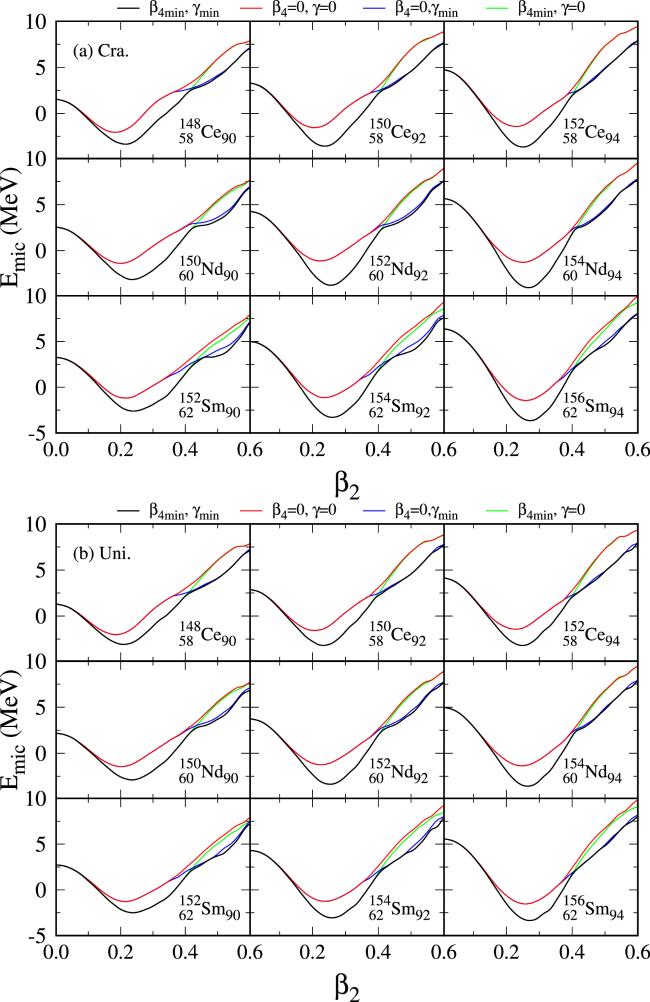

Figure 6. Four types of deformation energy curves, calculated by ‘cranking’ (top) and ‘universal’ (bottom) WS parameters [39, 47, 56], as the function of quadrupole deformation β2 for 9 nuclei 148,150,152Ce, 150,152,154Nd and 152,154,156Sm. Let us note that the lines with different colors, as denoted by the legends, represent whether or not the total energy at each β2 grid is minimized over other deformation parameter(s). For more details, see the text. |

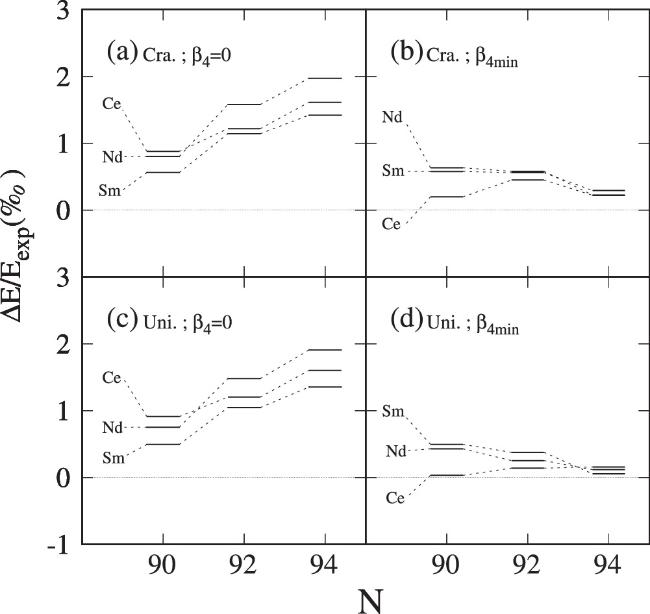

Figure 7. The calculated relative mass deviation (e.g. permillage error) between theory and experiment, with (b, d)/without (a, c) the inclusion of hexadecapole deformation β4, based on the cranking (a, b) and universal (c, d) parameter sets for 148,150,152Ce, 150,152,154Nd and 152,154,156Sm. See the text for more details. |

Table 4. The calculated macroscopic energy Emac, microscopic energy Emic, total energy Etot, experimental binding energy [3] ${E}_{\exp }$ and the deviation ΔE ($\equiv | {E}_{\mathrm{tot}}-{E}_{\exp }| $) between theory and experiment. The quantities with the superscripts a and b respectively correspond to the calculated results with cranking and universal WS parameter sets [39, 47, 56]. The italic denotes that the corresponding value is calculated without the inclusion of β4 deformation. All energies are in units of MeV. |

| Nuclear | Emac | ${E}_{\mathrm{mic}}^{a}$ | ${E}_{\mathrm{mic}}^{b}$ | ${E}_{\mathrm{tot}}^{a}$ | ${E}_{\mathrm{tot}}^{b}$ | ${E}_{\exp }$ | ΔEa | ΔEb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ${}_{58}^{148}$Ce90 | −1216.659 | −3.4065 | −3.1218 | −1220.066 | −1219.781 | −1219.577 | 0.489 | 0.204 |

| −2.0900 | −2.0509 | −1218.749 | −1218.710 | 0.828 | 0.867 | |||

| ${}_{58}^{150}$Ce92 | −1227.382 | −3.6231 | −3.2431 | −1231.005 | −1230.625 | −1230.168 | 0.837 | 0.457 |

| −1.5689 | −1.5888 | −1228.951 | −1228.971 | 1.217 | 1.197 | |||

| ${}_{58}^{152}$Ce94 | −1237.363 | −3.7043 | −3.2320 | −1241.067 | −1240.595 | −1240.472 | 0.595 | 0.123 |

| −1.4279 | −1.4396 | −1238.791 | −1238.803 | 1.681 | 1.669 | |||

| ${}_{60}^{150}$Nd90 | −1235.230 | −3.1964 | −2.9452 | −1238.426 | −1238.175 | −1237.437 | 0.989 | 0.738 |

| −1.4168 | −1.4805 | −1236.647 | −1236.711 | 0.790 | 0.726 | |||

| ${}_{60}^{152}$Nd92 | −1247.183 | −3.8363 | −3.4281 | −1251.019 | −1250.611 | −1250.049 | 0.970 | 0.562 |

| −1.1339 | −1.2594 | −1248.317 | −1248.442 | 1.732 | 1.607 | |||

| ${}_{60}^{154}$Nd94 | −1258.374 | −4.0602 | −3.6251 | −1262.434 | −1261.999 | −1261.867 | 0.567 | 0.132 |

| −1.2854 | −1.3667 | −1259.659 | −1259.741 | 2.208 | 2.126 | |||

| ${}_{62}^{152}$Sm90 | −1251.384 | −2.6054 | −2.5019 | −1253.989 | −1253.886 | −1253.097 | 0.892 | 0.789 |

| −1.1745 | −1.2600 | −1252.559 | −1252.644 | 0.538 | 0.453 | |||

| ${}_{62}^{154}$Sm92 | −1264.560 | −3.2883 | −3.0573 | −1267.848 | −1267.617 | −1266.933 | 0.915 | 0.684 |

| −1.1295 | −1.2517 | −1265.690 | −1265.812 | 1.243 | 1.121 | |||

| ${}_{62}^{156}$Sm94 | −1276.957 | −3.6424 | −3.3380 | −1280.599 | −1280.295 | −1279.980 | 0.619 | 0.315 |

| −1.4474 | −1.5342 | −1278.404 | −1278.491 | 1.576 | 1.489 |