1. Introduction

2. Traversability conditions for wormhole

| 1. | 1. Redshift function: The redshift function Φ(r) needs to have a finite value across the entire space-time. Additionally, the redshift function must adhere to the constraint of having no event horizon, which allows for a two-way journey through the wormhole. |

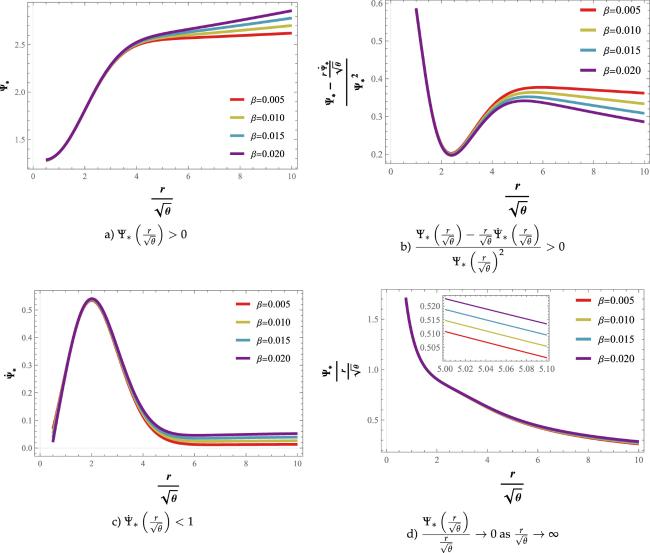

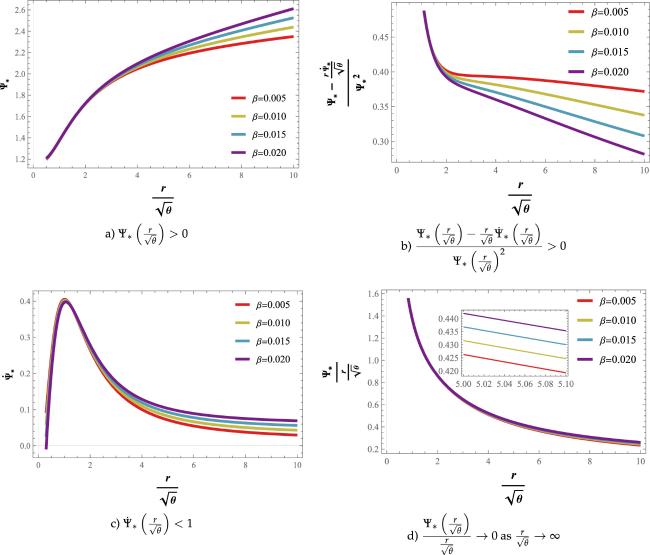

| 2. | 2. Shape function: The shape function $\Psi$(r) characterizes the geometry of the traversable wormhole. Therefore, $\Psi$(r) must satisfy the following conditions: Throat condition: The value of the function $\Psi$(r) at the throat is r0 and hence $1-\tfrac{{\rm{\Psi }}(r)}{r}\gt 0$ for r > r0. Flaring-out condition: The radial differential of the shape function, ${\rm{\Psi }}^{\prime} (r)$ at the throat should satisfy, ${\rm{\Psi }}^{\prime} ({r}_{0})\lt 1.$ Asymptotic Flatness condition: As r → ∞ , $\tfrac{{\rm{\Psi }}(r)}{r}\to 0$. |

| 3. | 3. Proper radial distance function: This function should be finite everywhere in the domain. In magnitude, it decreases from the upper universe to the throat and then increases from the throat to the lower universe. The proper radial distance function is expressed as, $\begin{eqnarray}l(r)=\pm {\int }_{{r}_{0}}^{r}\displaystyle \frac{{\rm{d}}{r}}{\sqrt{\tfrac{r-{\rm{\Psi }}(r)}{r}}}.\end{eqnarray}$ |

3. Mathematical formulations of $f({ \mathcal Q },{ \mathcal T })$ gravity

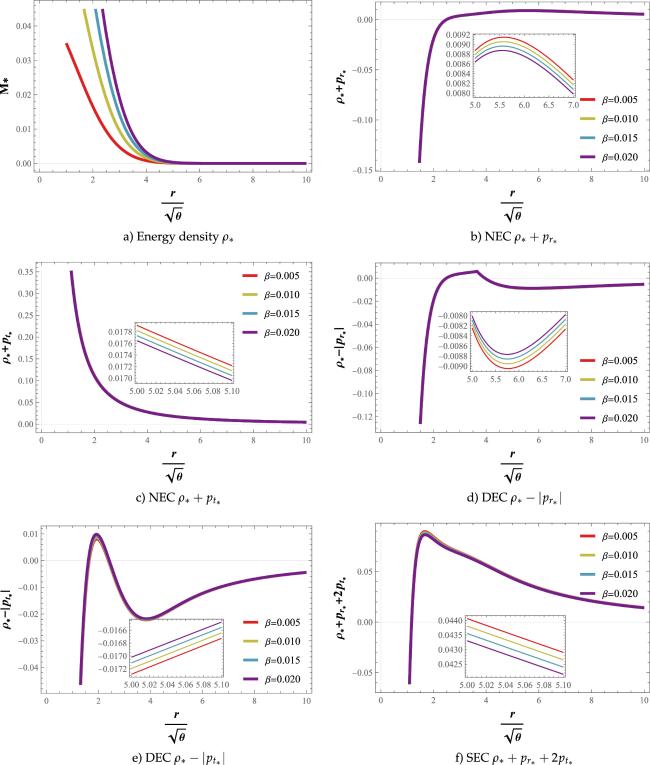

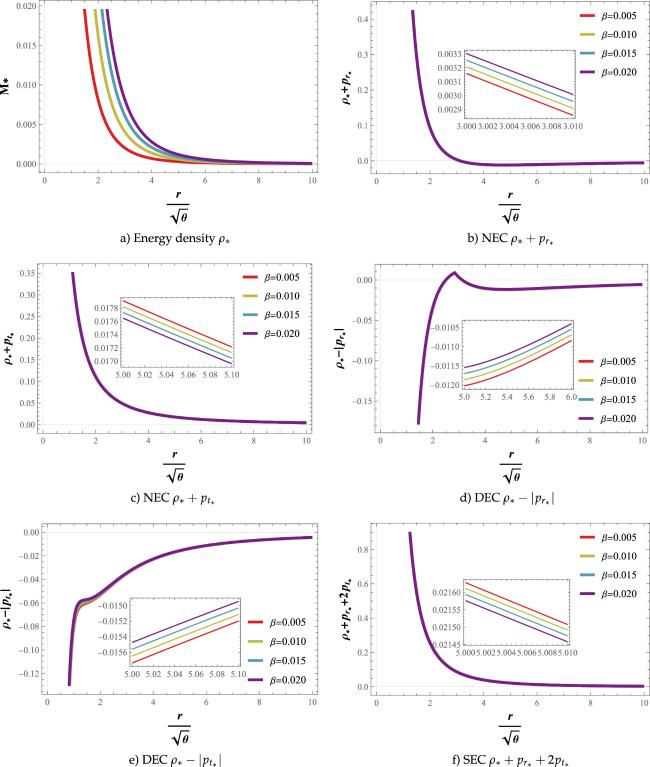

3.1. Energy condition

| • | Null Energy Conditions: ρ + pt ≥ 0 and ρ + pr ≥ 0. |

| • | Weak Energy Conditions: ρ ≥ 0 ⇒ ρ + pt ≥ 0 and ρ + pr ≥ 0. |

| • | Strong Energy Conditions: ρ + pj ≥ 0 ⇒ ρ + ∑jpj ≥ 0 ∀j. |

| • | Dominant Energy Conditions: ρ ≥ 0 ⇒ ρ − ∣pr∣ ≥ 0 and ρ − ∣pt∣ ≥ 0. |

3.2. Conformal killing vectors

4. Wormhole model in $f({ \mathcal Q },{ \mathcal T })$ gravity

4.1. Gaussian energy density

Figure 1. The graphical behavior of shape function $\Psi$* for Gaussian non-commutative geometry with ${M}_{* }=7.25,\alpha =0.45,{{ \mathcal C }}_{2}=2$ and $\tfrac{{r}_{0}}{\sqrt{\theta }}=1.6$. |

Figure 2. Gaussian Source: The profile of energy density and energy conditions with respect to $\tfrac{r}{\sqrt{\theta }}$ for different values of β with fixed parameters ${M}_{* }=7.25,\alpha =0.45,{{ \mathcal C }}_{2}=2$ and $\tfrac{{r}_{0}}{\sqrt{\theta }}=1.6$. |

4.2. Lorentzian energy density

Figure 3. The graphical behavior of shape function $\Psi$* for Lorentzian non-commutative geometry with ${M}_{* }=7.25,\alpha =0.45,{{ \mathcal C }}_{2}=2$ and $\tfrac{{r}_{0}}{\sqrt{\theta }}=1.6$. |

Figure 4. Lorentzian Source: The profile of energy density and energy conditions with respect to $\tfrac{r}{\sqrt{\theta }}$ for different values of β with fixed parameters ${M}_{* }=7.25,\alpha =0.45,{{ \mathcal C }}_{2}=2$ and $\tfrac{{r}_{0}}{\sqrt{\theta }}=1.6$. |

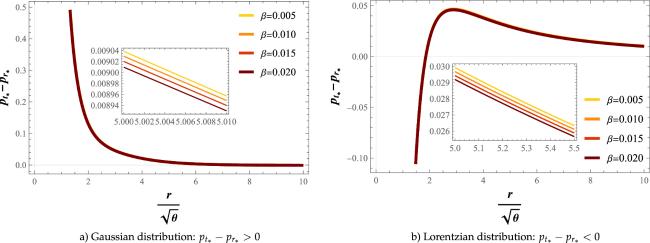

5. Effect of anisotropy

Figure 5. The graphical representation of anisotropy for both distributions. |