1. Introduction

2. Nonreciprocal intra-cell coupled circular chains

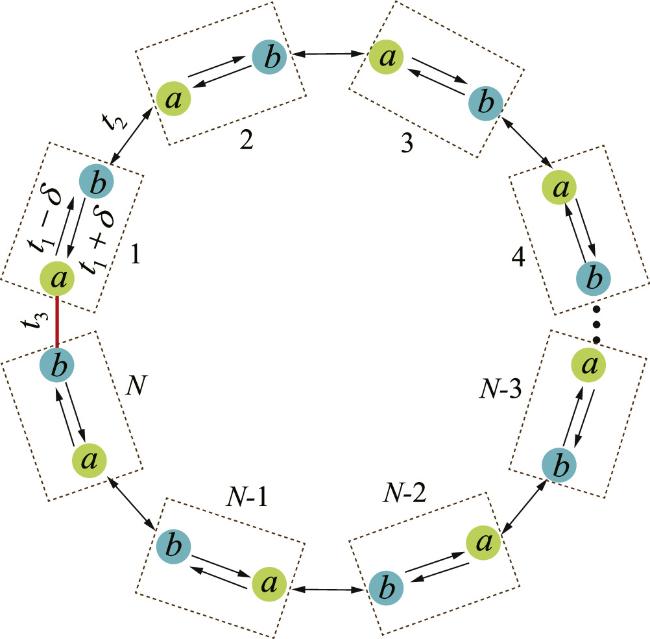

Figure 1. Schematic of a circular non-Hermitian chain. The circular non-Hermitian chain contains N unit cells (black dashed rectangle). Each unit cell contains two kinds of sites a and b. The couplings in the same unit cell take nonreciprocal configurations and the couplings between two adjacent unit cells take reciprocal configurations. The first site a1 couples with the last site bN via t3. |

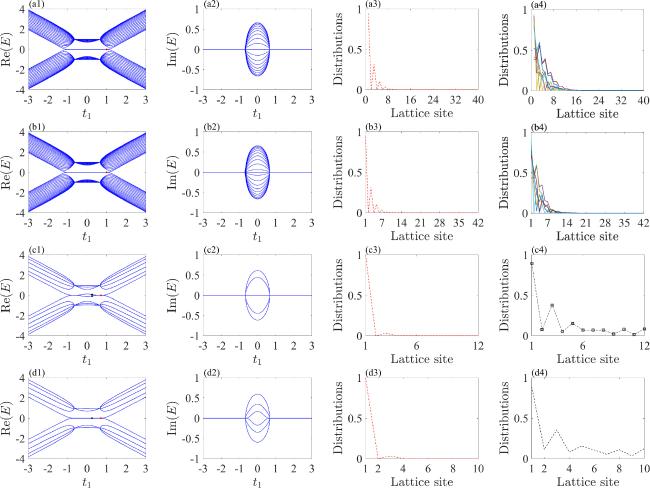

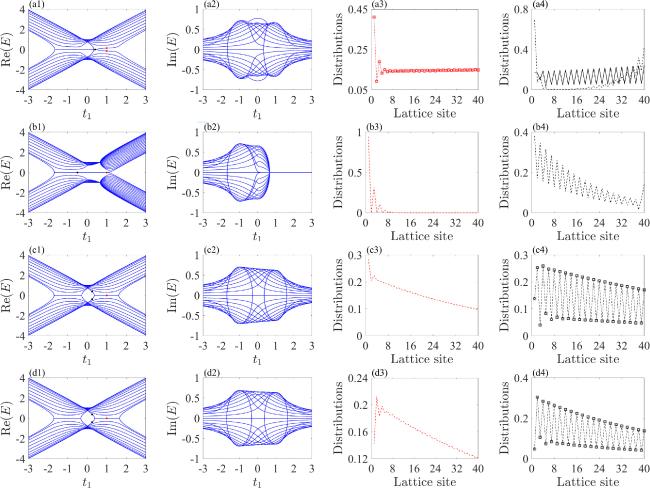

Figure 2. The energy spectra and distributions of states for an open non-Hermitian chain. (a1) The real part of the energy spectrum when N = 20. (a2) The imaginary part of the energy spectrum when N = 20. (a3) The distributions of the red dot in (a1). (a4) The distributions of eight randomly chosen bulk states. (b1)–(b4) The same projects as in (a1)–(a4) when N = 21. (c1) The real part of the energy spectrum when N = 6. (c2) The imaginary part of the energy spectrum when N = 6. (c3) The distributions of the red dot in (c1). (c4) The distributions of the black dots in (c1). (d1)–(d4) The same projects as in (c1)–(c4) when N = 5. Other parameters satisfy δ = 2/3 and t2 = 1. |

2.1. The case of reciprocal t3

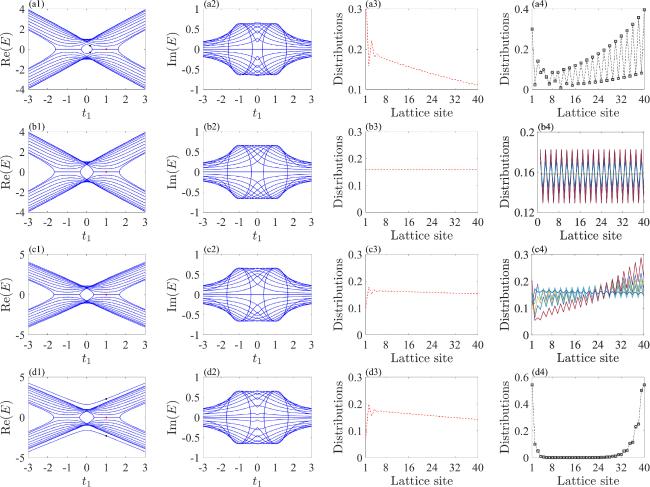

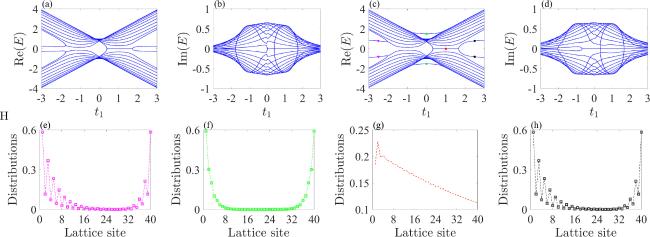

Figure 3. The energy spectra and distributions of states for a circular non-Hermitian chain. (a1) The real part of the energy spectrum when t3 = 0.3. (a2) The imaginary part of the energy spectrum when t3 = 0.3. (a3) The distributions of the red dot in (a1). (a4) The distributions of the black dots in (a1). (b1) The real part of the energy spectrum when t3 = 1. (b2) The imaginary part of the energy spectrum when t3 = 1. (b3) The distributions of the red dot in (b1). (b4) The distributions of eight randomly chosen bulk states in (b1). (c1)–(c4) The same projects as in (b1)–(b4) when t3 = 1.5. (d1) The real part of the energy spectrum when t3 = 2. (d2) The imaginary part of the energy spectrum when t3 = 2. (d3) The distributions of the red dot in (d1). (d4) The distributions of the black dots in (d1). Other parameters satisfy δ = 2/3, t2 = 1, and N = 20. |

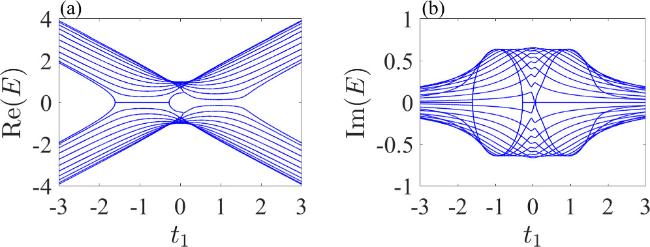

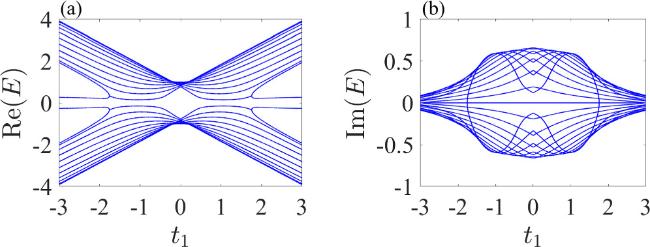

Figure 4. The even–odd effect of unit cell corresponding to a large number of unit cell N = 21. (a) The real part of energy spectrum. (b) The imaginary part of the energy spectrum. Other parameters satisfy δ = 2/3, t2 = 1, and t3 = 0.3. |

2.2. The case of nonreciprocal t3

Figure 5. The energy spectra and distributions of states for a circular non-Hermitian chain with nonreciprocal t3. (a1) The real part of the energy spectrum when t3 = 0.3. (a2) The imaginary part of the energy spectrum when t3 = 0.3. (a3) The distributions of the red dots in (a1). (a4) The distributions of the black dot in (a1). (b1) The real part of the energy spectrum when t3 = δ. (b2) The imaginary part of the energy spectrum when t3 = δ. (b3) The distributions of the red dot in (b1). (b4) The distributions of black dot in (b1). (c1)-(c4) and (d1)-(d4) The same projects as in (b1)-(b4) when t3 = 1 and t3 = 1.5. Other parameters satisfy δ = 2/3, t2 = 1, and N = 20. |

3. Circular chain with nonreciprocal inter-cell couplings

3.1. The case of reciprocal t3

Figure 6. The energy spectra and distributions of states for a circular non-Hermitian chain with reciprocal t3. (a) The real part of the energy spectrum when t3 = 0.3. (b) The imaginary part of the energy spectrum when t3 = 0.3. (c) The real part of the energy spectrum when t3 = 1. (d) The imaginary part of the energy spectrum when t3 = 1. (e)–(h) The distributions of the purple dots, green dots, red dot, and black dots in (c). Other parameters satisfy δ = 2/3, t2 = 1, and N = 20. |

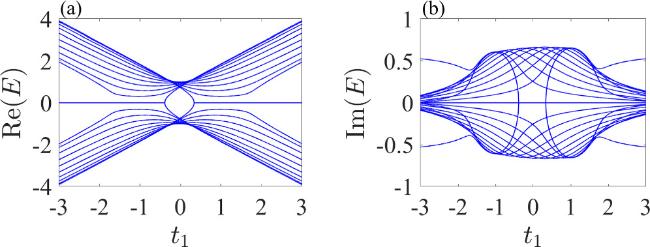

Figure 7. The even–odd effect of unit cell corresponding to a large number of unit cell N = 21 for (a) the real part of the spectrum and for (b) the imaginary part of the spectrum. Other parameters satisfy δ = 2/3, t2 = 1, and t3 = 0.3. |

3.2. The case of nonreciprocal t3

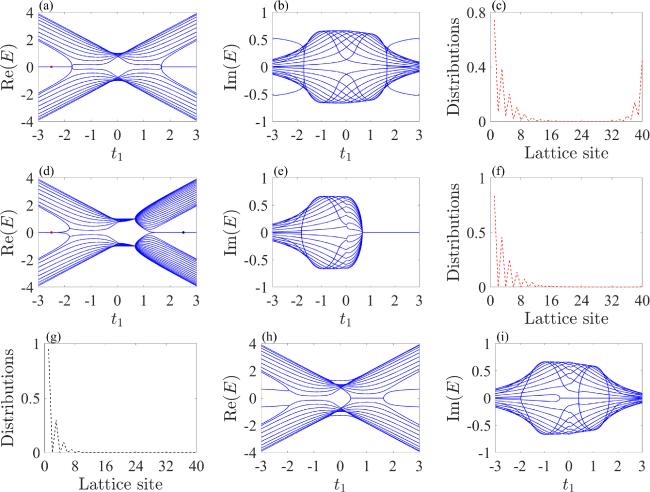

Figure 8. The energy spectra and distributions of states for a circular non-Hermitian chain with nonreciprocal t3. (a) The real part of the energy spectrum when t3 = 0.3. (b) The imaginary part of the energy spectrum when t3 = 0.3. (c) The distributions of the red dot in (a). (d) The real part of the energy spectrum when t3 = δ. (e) The imaginary part of the energy spectrum when t3 = δ. (f) and (g) The distributions of the red dot and black dot in (d). (h) The real part of the energy spectrum when t3 = 1. (i) The imaginary part of the energy spectrum when t3 = 1. Other parameters satisfy δ = 2/3, t2 = 1, and N = 20. |

Figure 9. The energy spectra and distributions of states for a circular non-Hermitian chain with the inversion of nonreciprocal hopping, i.e., $({t}_{3}-\delta ){a}_{1}^{\dagger }{b}_{N}$ and $({t}_{3}+\delta ){b}_{N}^{\dagger }{a}_{1}$. (a) The real part of the energy spectrum when t3 = 0.3. (b) The imaginary part of the energy spectrum when t3 = 0.3. Other parameters satisfy δ = 2/3, t2 = 1, and N = 20. |