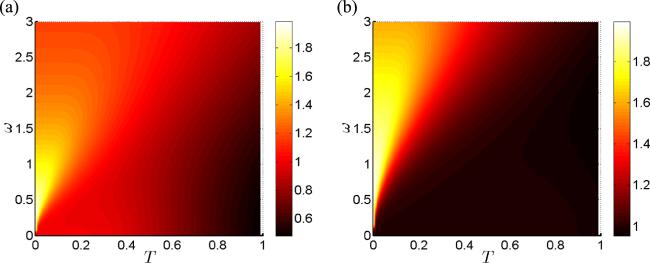

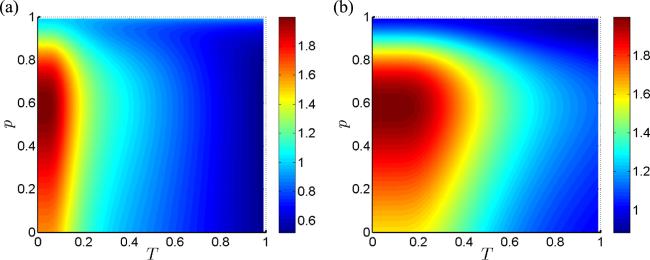

The effects of the temperature on the dense coding capacity are clearly visible in figure

3, where we consider

χ(

ρT) as a function of

T and

ω. As the temperature increases, thermal fluctuations become more significant. In general, higher temperatures can introduce more noise and reduce the fidelity of quantum information processing. These factors result in a decrease in the dense coding capacity for larger

T, which is visible in figure

3(a) and (b). In the domain of

ω, the dense coding capacity exhibits non-linear behavior. The higher energy difference initially leads to an increased capacity, as there is more energy available for quantum information processing. However, at extremely high values of

ω, other factors, like increased thermal effects, counteract this trend. By comparing figure

3(a) and (b), we notice an interplay between gravitational effects and the quantum information processing capabilities. For instance, when

γ = 1, we have valid dense coding at low temperatures. However, when

γ = 3, the optimal dense coding is represented by a larger and brighter area (see white and yellow areas) in the domain of (

T,

ω) and we have valid dense coding even at high temperatures.