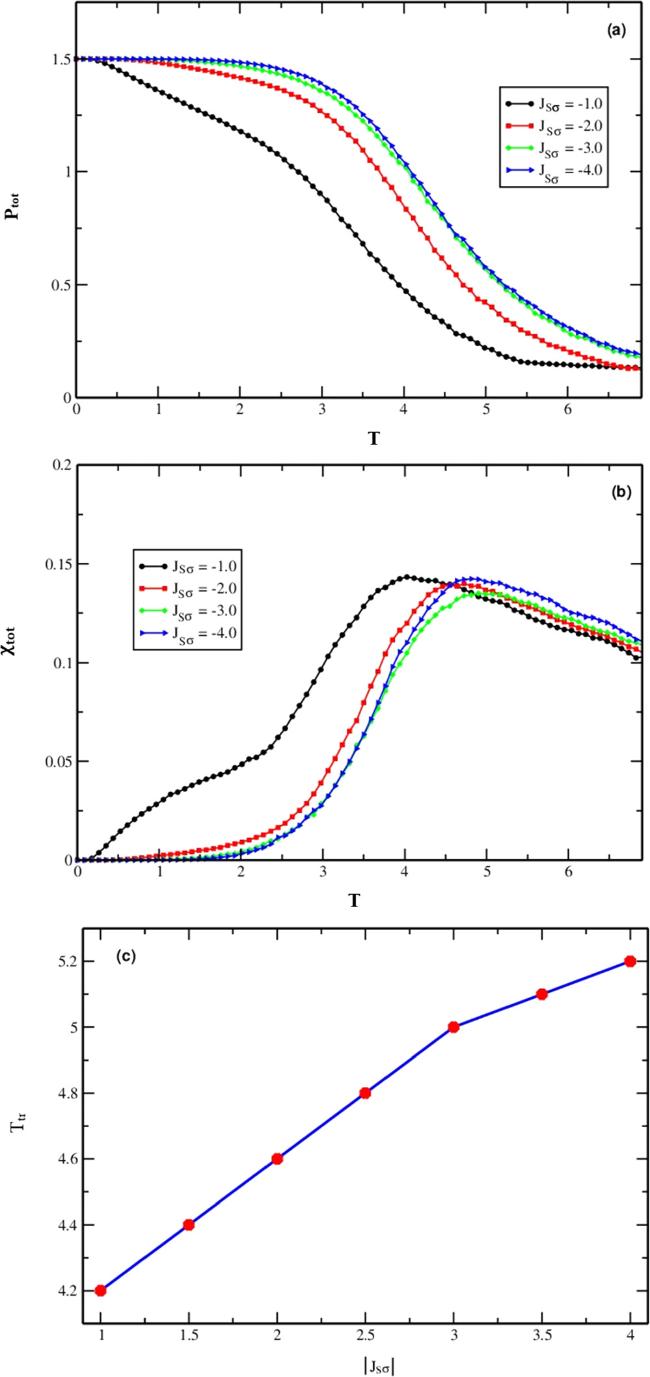

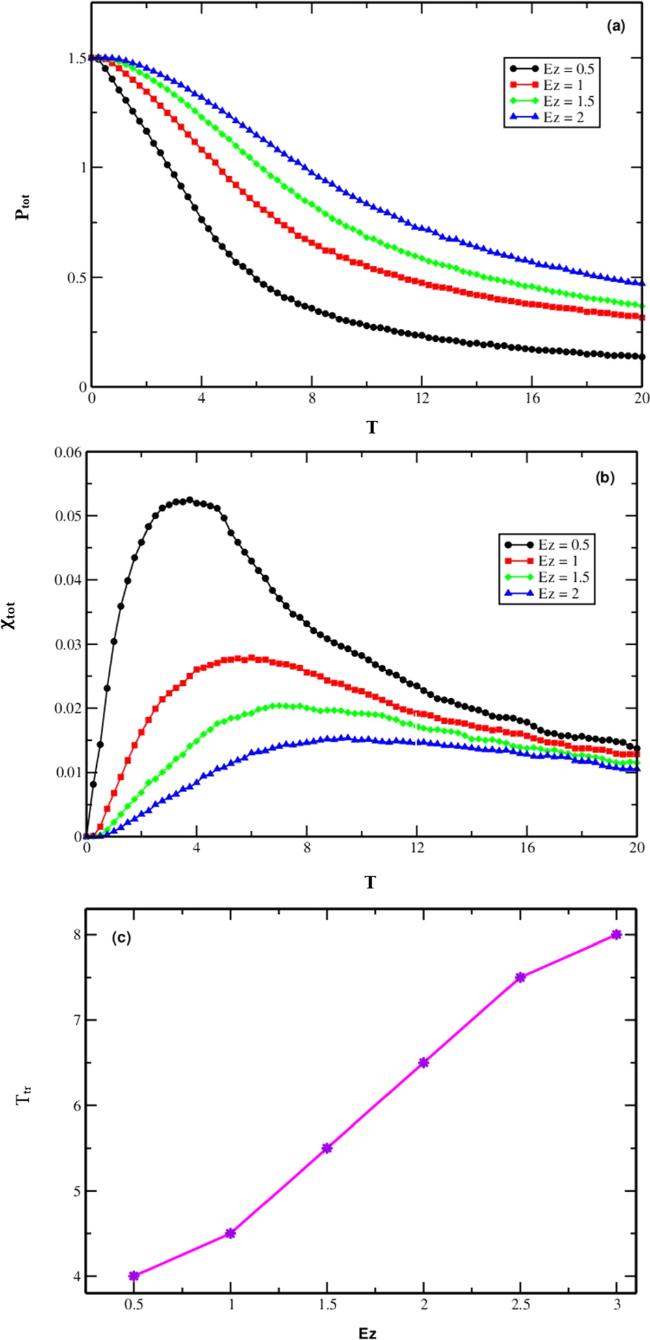

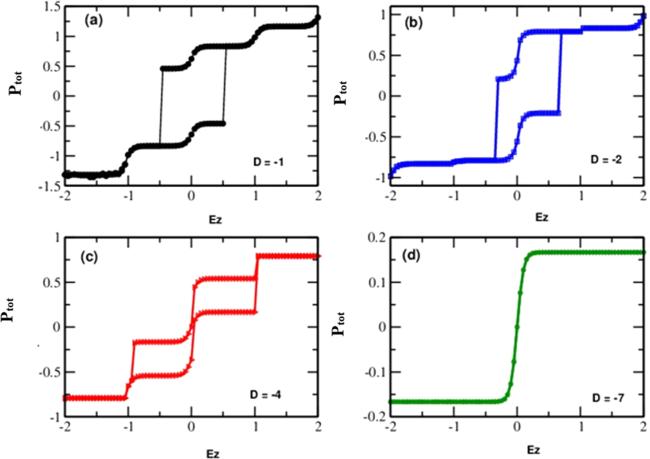

Pursuing a similar rationale, we investigated the influence of the electric field parameter

Ez on the thermal tendencies of total polarizations and total dielectric susceptibility across various

Ez values (

Ez = 0.5, 1, 1.5, and 2). The outcomes are presented in figures

6(a) and (b), assuming

D = 0,

Jss = 1, and

JSσ = −0.01. As depicted in figure

6(a), we observed that the total polarization diminishes towards an earlier transition temperature

Ttr for lower external longitudinal electric field values compared to higher ones. This effect arises due to the interplay between the promoting influence of the external longitudinal electric field on order within the system and the temperature’s role in promoting disorder. Additionally, figure

6(b) showcases the thermal total dielectric susceptibility. The transition temperature values align with the peaks of the total dielectric susceptibility, with

Ttr values approximately ≈ 4, 4.5, 5.5, and 6.5 for

Ez values of 0.5, 1, 1.5, and 2 respectively. To synthesize the findings from figures

6(a) and (b), we present a graphical representation in figure

6(c), illustrating the correlation between the transition temperature and the

Ez parameter. In order to consolidate the results depicted in figures

6(a) and (b), we have included a graphical representation in figure

6(c) that illustrates the correlation between the transition temperature and the parameter

Ez. The figure effectively demonstrates that there was an almost linear increase in the transition temperature as the ferrielectric parameter

Ez is progressively elevated.