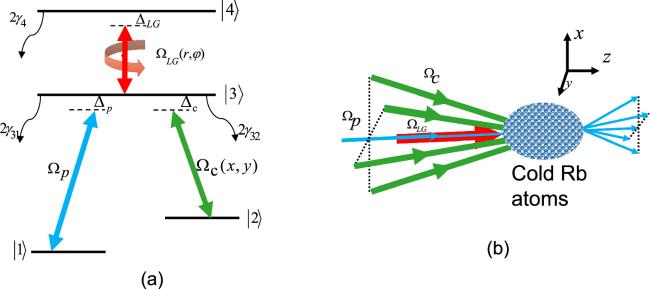

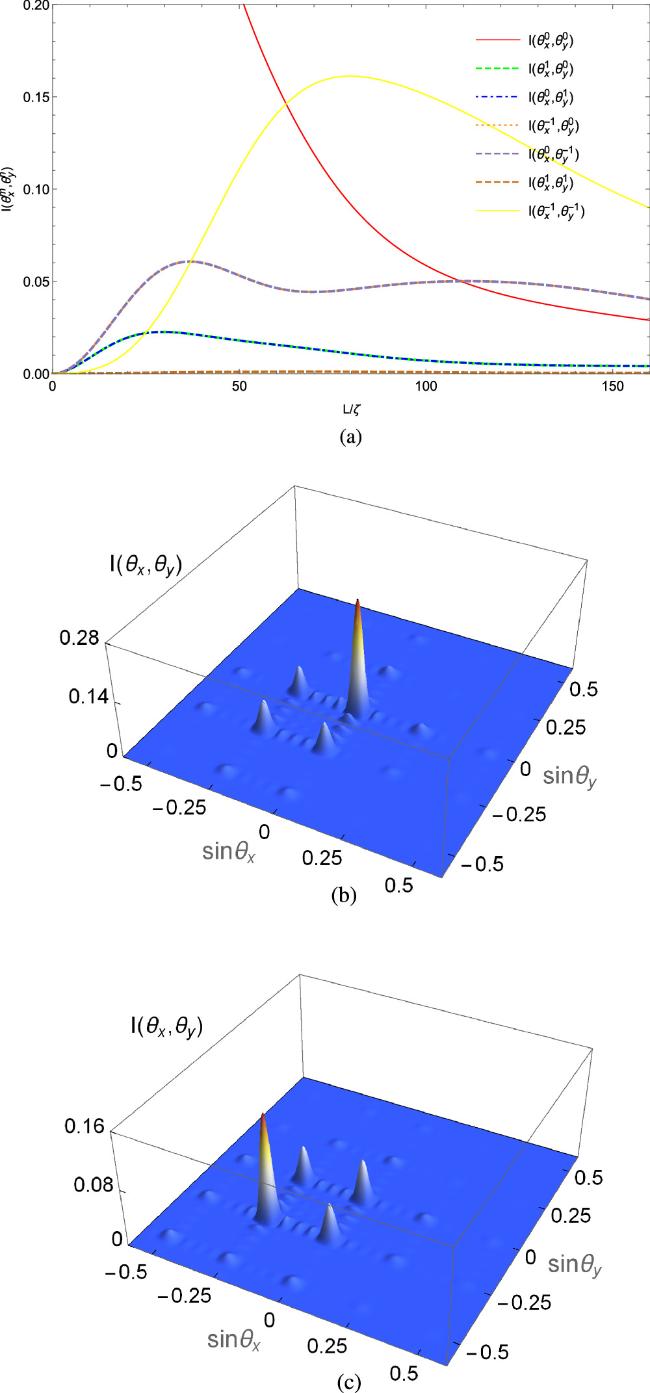

In this section, we will investigate the effects of different system parameters on the Fraunhofer diffraction pattern and intensity of the weak probe field through the four-level inverted-Y-type atomic medium. As can be seen from equations (

7)–(

10), the diffraction properties of the probe field strongly depend on the amplitude and phase modulation of the 2D grating. In figures

2 and

3, we plot amplitude and phase modulation with respect to

x/Λ

x and

y/Λ

y, as well as the relationship of the diffraction pattern to $\sin {\theta }_{x}$ and $\sin {\theta }_{x}$ for different probe field detunings. When Δ

p = − 6

γ3, the amplitude modulation function ∣

T(

x,

y)∣ shows a hill-like structure in the central portion of a spatial period with the transmissivity being about 100%, as shown in figure

2(a). Meanwhile, the phase modulation function

φ(

x,

y) displays a cylinder with modulation height of 12 in the central position, but the average value of the other regions is −4 (see figure

2(b)). Under the combined effect of amplitude and phase modulation, the probe field displays four diffraction peaks in domain I ($0\leqslant \sin {\theta }_{x}\leqslant 0.5,0\leqslant \sin {\theta }_{y}\leqslant 0.5$). As shown in figure

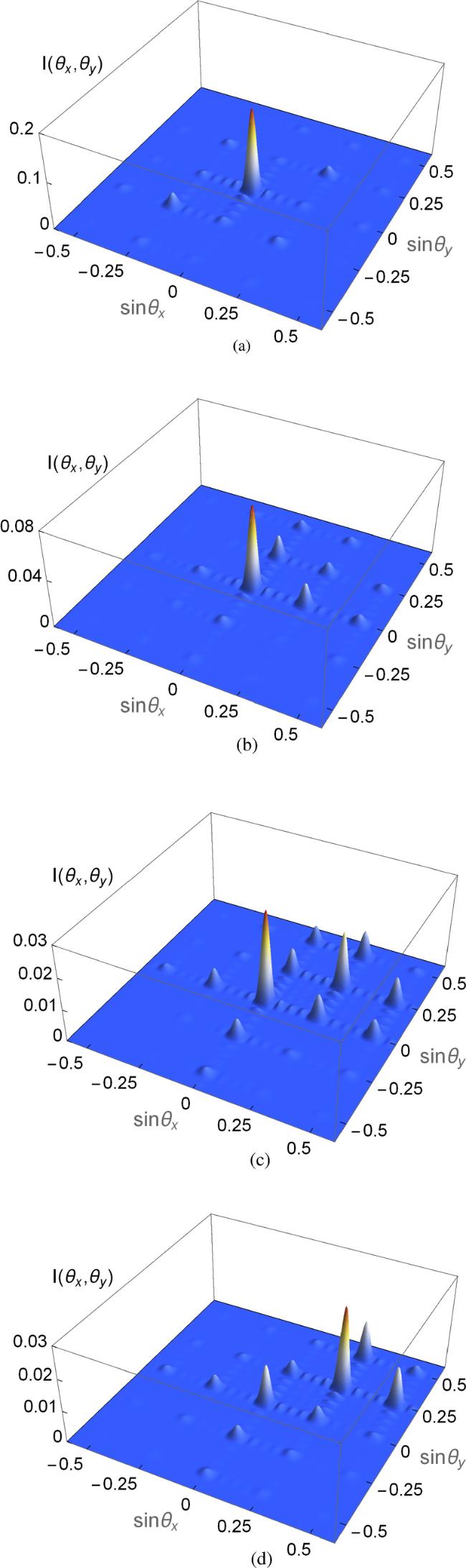

2(c), the intensity of the central peak ($\sin {\theta }_{x}=0,\sin {\theta }_{y}=0$) is about 0.12, and the intensities of other (1, 0), (0, 1) and (1, 1) orders located at ($\sin {\theta }_{x}=0.25,\sin {\theta }_{y}=0$), ($\sin {\theta }_{x}=0,\sin {\theta }_{y}=0.25$) and($\sin {\theta }_{x}=0.25,\sin {\theta }_{y}=0.25$) are 0.08, 0.08 and 0.1, respectively. As the probe field detuning Δ

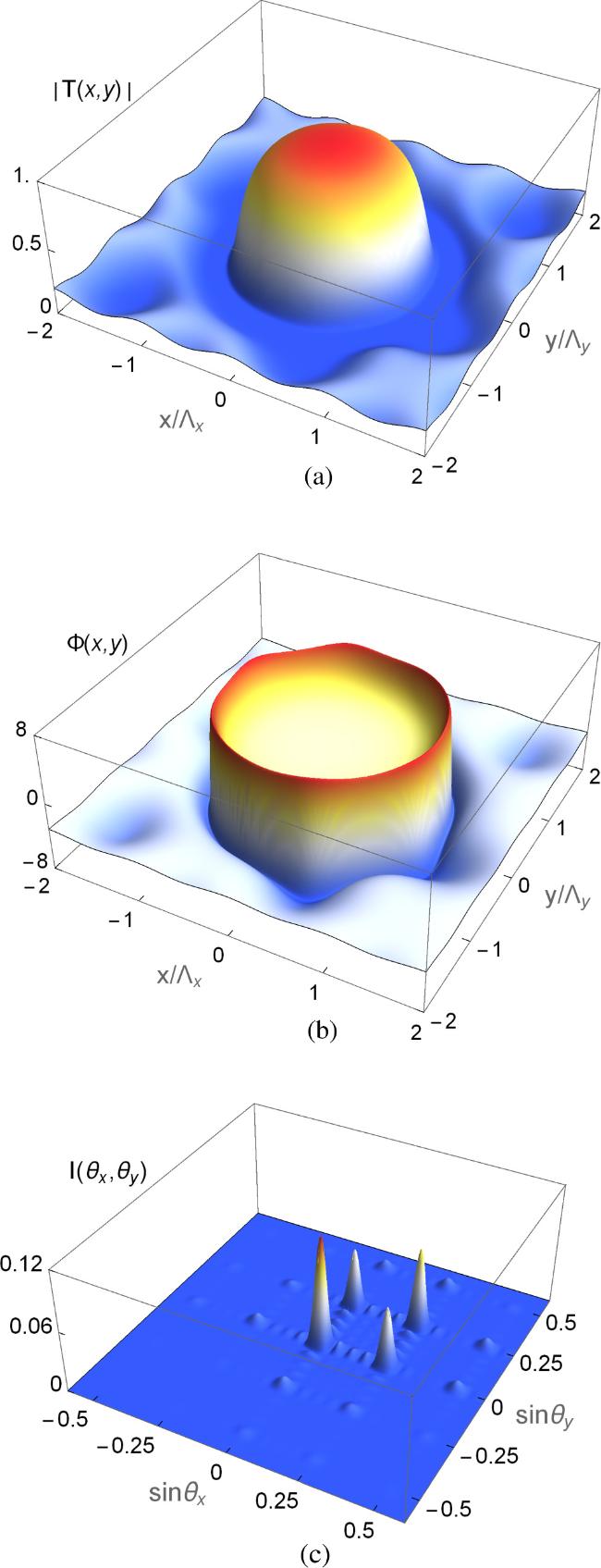

p is tuned to −4

γ3, it can be seen that the amplitude modulation function ∣

T(

x,

y)∣ still shows a hill-like structure with 100% transmissivity, and only the range of the hill-like structure increases slightly (see figure

3(a)). However, the shape and depth of the phase modulation

φ(

x,

y) change dramatically. The central region changes to a yurt-like shape and two sharp modulation peaks appear on the diagonal of the first and third quadrants. This shows that the atomic medium has a large phase modulation ability in most of the range of a spatial period (see figure

3(b)). Under this condition, the diffraction peaks of domain I are completely suppressed and the probe field is mainly diffracted into domain III ($-0.5\leqslant \sin {\theta }_{x}\,\leqslant 0,-0.5\leqslant \sin {\theta }_{y}\leqslant 0$). The diffraction intensities of the (0, −1), (−1, 0) and (−1, −1) orders corresponding to ($\sin {\theta }_{x}=0,\sin {\theta }_{y}=-0.25$), ($\sin {\theta }_{x}=-0.25,\sin {\theta }_{y}=0$) and ($\sin {\theta }_{x}=-0.25,\sin {\theta }_{y}=-0.25$) increase significantly (see figure

3(c)). In particular, the (−1, −1) order diffraction intensity of the probe field can reach about 0.16. Therefore, the diffraction properties and patterns of the asymmetric 2D diffraction grating can be controlled effectively by probe field detuning.