1. Introduction

2. ${ \mathcal F }({ \mathcal R },{{\mathscr{L}}}_{m})$-Gravity and field equations

3. The geometry of wormholes in ${ \mathcal F }({ \mathcal R },{{\mathscr{L}}}_{m})$

| 1. | 1. Here r lies between r0 ≤ r < ∞ , r0 is the throat radius. |

| 2. | 2. The SF must follow ${N}_{{ \mathcal S }}({r}_{0})={r}_{0}$, ${N}_{{ \mathcal S }}(r)\lt r$ for r > r0 that is out of throat. |

| 3. | 3. For a throat problem that is flare-up, ${N}_{{ \mathcal S }}(r)$ has to follow, ${N}_{{ \mathcal S }}^{{\prime} }({r}_{0})\lt 1$ i.e. $\tfrac{{N}_{{ \mathcal S }}(r)-{{rN}}_{{ \mathcal S }}^{{\prime} }(r)}{{N}_{{ \mathcal S }}^{2}(r)}\gt 0$. |

| 4. | 4. For asymptotical flatness: ${\mathrm{lim}}_{r\to \infty }\tfrac{{N}_{{ \mathcal S }}(r)}{r}=0$. |

| 5. | 5. To prevent an event horizon, the redshift function must be finite everywhere. |

4. Energy conditions

| • | Null Energy Condition: $\rho +{{ \mathcal P }}_{t}\geqslant 0$, $\rho +{{ \mathcal P }}_{r}\geqslant 0$. |

| • | Weak Energy Condition: ρ > 0, $\rho +{{ \mathcal P }}_{t}\geqslant 0$, $\rho +{{ \mathcal P }}_{r}\geqslant 0$. |

| • | Strong Energy Condition: $\rho +{{ \mathcal P }}_{t}\geqslant 0$, $\rho +{{ \mathcal P }}_{r}\geqslant 0$, $\rho +{{ \mathcal P }}_{r}+2{{ \mathcal P }}_{t}\geqslant 0$. |

| • | Dominant Energy Condition: $\rho \gt | {{ \mathcal P }}_{t}| $, $\rho \gt | {{ \mathcal P }}_{r}| $. |

5. Model for wormholes

6. Strategies of wormhole solutions through novel shape function

6.1. Wormhole model—I

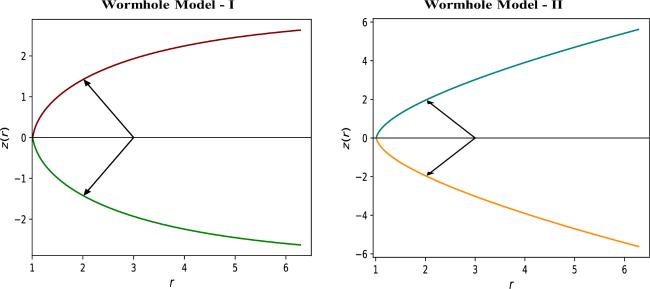

Figure 1. Two-dimensional graphic representation of embedding diagrams of wormhole w.r.t SF-1 (left) and w.r.t SF-2 (right). |

Figure 2. Wormhole surface diagram w.r.t SF-1 (left) and w.r.t SF-2 (right) |

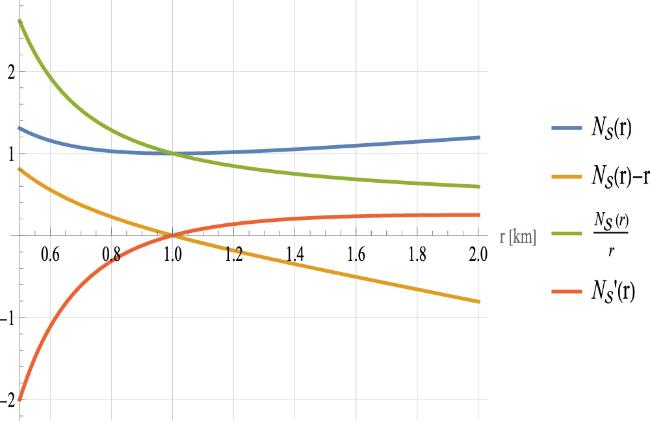

Figure 3. Attributes of SF-1 with r0 = 1 and δ = 0.5 |

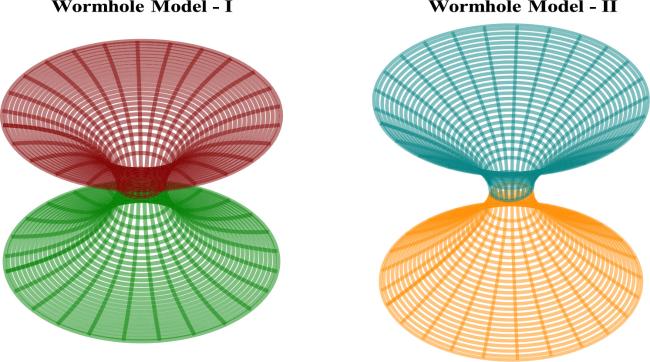

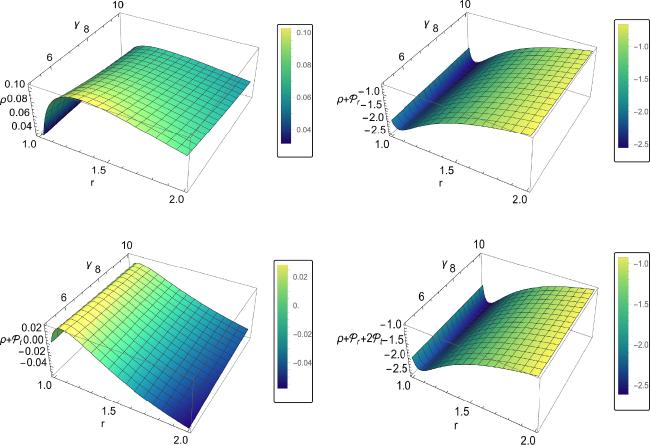

Figure 4. Behavior of ρ (top left panel), $\rho +{{ \mathcal P }}_{r}$ (top right panel), $\rho +{{ \mathcal P }}_{t}$ (bottom left panel), and $\rho +{{ \mathcal P }}_{r}+2{{ \mathcal P }}_{t}$ (right bottom panel) with δ = 0.5, γ ∈ [5, 10] and r0 = 1 for WH-I . |

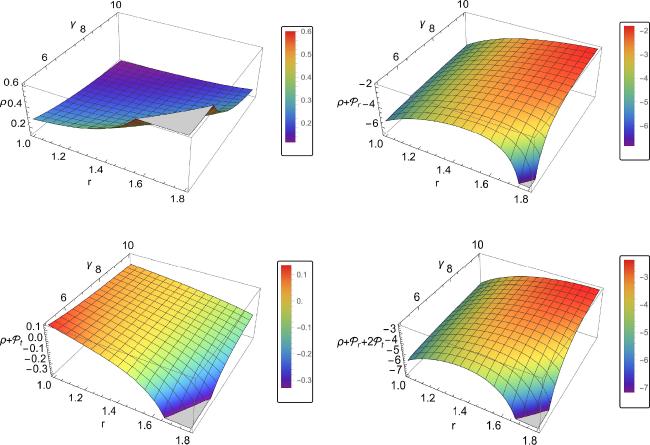

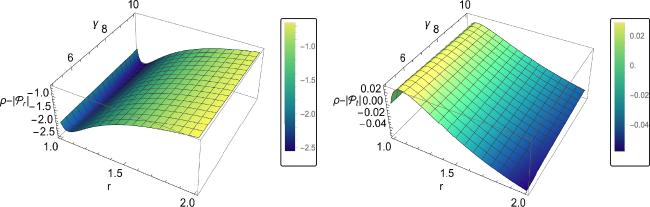

Figure 5. Behavior of $\rho -| {{ \mathcal P }}_{r}| $ (left panel) and $\rho -| {{ \mathcal P }}_{t}| $ (right panel) with δ = 0.5, γ ∈ [5, 10] and r0 = 1 for WH-I. |

Table 1. Aspects of different strategies with execution of physical expressions for both cases. |

| Strategy | Physical Expressions | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| SF-1: | ρ | >0 for r ≥ 1 |

| ${N}_{{ \mathcal S }}(r)={r}_{0}{\left(\tfrac{\cosh ({r}_{0})}{\cosh (r)}\right)}^{\delta }$, δ > 0 | $\rho +{{ \mathcal P }}_{r}$ | <0 for r ≥ 1 |

| Parameters | $\rho +{{ \mathcal P }}_{t}$ | >0 for 1 ≤ r < 1.368, |

| γ ∈ [5, 10], | <0 for 1.368 < r < 1.8 & | |

| r0 = 1 & δ = 0.5 | ≥0 for r ≥ 1.8 | |

| $\rho -| {{ \mathcal P }}_{r}| $ | <0 for r ≥ 1 | |

| $\rho -| {{ \mathcal P }}_{t}| $ | >0 for 1 ≤ r < 1.366, | |

| <0 for 1.366 < r < 1.8 & | ||

| ≤0 for r ≥ 1.8 | ||

| $\rho +{{ \mathcal P }}_{r}+2{{ \mathcal P }}_{t}$ | <0 for r ≥ 1 | |

| ${N}_{{ \mathcal S }}(r)$ | ${N}_{{ \mathcal S }}(r)\gt 0$ w.r.t radial coordinate r | |

| ${N}_{{ \mathcal S }}(r)$ | ${N}_{{ \mathcal S }}(r)-r\,=\,0$ with r0 = 1. | |

| ${N}_{{ \mathcal S }}^{{\prime} }(r)$ | ${N}_{{ \mathcal S }}^{{\prime} }\lt 1$ when r ≥ r0. | |

| $\tfrac{{N}_{{ \mathcal S }}(r)}{r}$ | $\tfrac{{N}_{{ \mathcal S }}(r)}{r}\to 0$ as r → ∞ . | |

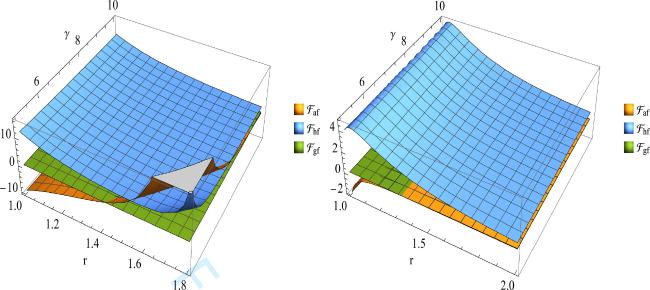

| ${{\mathscr{F}}}_{{hf}}+{{\mathscr{F}}}_{{gf}}+{{\mathscr{F}}}_{{af}}=0$ | Satisfied . | |

| ${ \mathcal V }{ \mathcal I }{ \mathcal Q }=8\pi {\int }_{{r}_{0}}^{{r}_{1}}(\rho +{{ \mathcal P }}_{r}){r}^{2}{\rm{d}}r$ | ${ \mathcal V }{ \mathcal I }{ \mathcal Q }\to 0$ as r1 → r0. | |

| | ||

| SF-2: | ρ | >0 for r ≥ 1 |

| ${N}_{{ \mathcal S }}(r)=\tfrac{1}{r}+\mathrm{log}\left(\tfrac{r}{{r}_{0}}\right)$. | $\rho +{{ \mathcal P }}_{r}$ | <0 for r ≥ 1 |

| Parameters | $\rho +{{ \mathcal P }}_{t}$ | >0 for 1 ≤ r < 1.364 & |

| <0 for r ≥ 1.364 | ||

| γ ∈ [5, 10] & r0 = 1. | $\rho -| {{ \mathcal P }}_{r}| $ | <0 for r ≥ 1 |

| $\rho -| {{ \mathcal P }}_{t}| $ | >0 for 1 ≤ r < 1.366 & | |

| <0 for r ≥ 1.366 | ||

| $\rho +{{ \mathcal P }}_{r}+2{{ \mathcal P }}_{t}$ | <0 for r ≥ 1 | |

| ${N}_{{ \mathcal S }}(r)$ | ${N}_{{ \mathcal S }}(r)\gt 0$ w.r.t radial coordinate r | |

| ${N}_{{ \mathcal S }}(r)-r$ | ${N}_{{ \mathcal S }}(r)(r)-r\,=\,0$ with r0 = 1. | |

| ${N}_{{ \mathcal S }}^{{\prime} }(r)$ | ${N}_{{ \mathcal S }}^{{\prime} }\lt 1$ when r ≥ r0. | |

| $\tfrac{{N}_{{ \mathcal S }}(r)}{r}$ | $\tfrac{{N}_{{ \mathcal S }}(r)}{r}\to 0$ as r → ∞ . | |

| ${{\mathscr{F}}}_{{hf}}+{{\mathscr{F}}}_{{gf}}+{{\mathscr{F}}}_{{af}}=0$ | Satisfied. | |

| ${ \mathcal V }{ \mathcal I }{ \mathcal Q }=8\pi {\int }_{{r}_{0}}^{{r}_{1}}(\rho +{{ \mathcal P }}_{r}){r}^{2}{\rm{d}}r$ | ${ \mathcal V }{ \mathcal I }{ \mathcal Q }\to 0$ as r1 → r0. | |

6.2. Wormhole model—II

Figure 6. Characteristics of SF-2 with r0 = 1 |

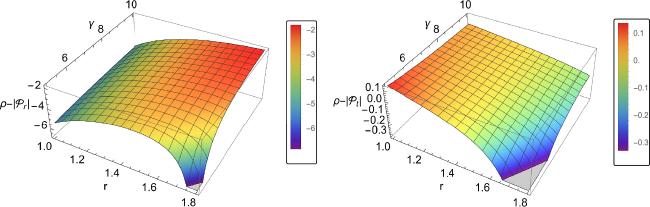

Figure 7. Behavior of ρ (top left panel), $\rho +{{ \mathcal P }}_{r}$ (top right panel), $\rho +{{ \mathcal P }}_{r}$ (bottom left panel), and $\rho +{{ \mathcal P }}_{r}+2{{ \mathcal P }}_{t}$ (right bottom panel) with γ ∈ [5, 10] and r0 = 1 for WH-II. |

Figure 8. Behavior of $\rho -| {{ \mathcal P }}_{r}| $ (left panel) and $\rho -| {{ \mathcal P }}_{t}| $ (right panel) with γ ∈ [5, 10] and r0 = 1 for WH-II. |

7. Equilibrium condition

| ${{\mathscr{F}}}_{{\bf{gf}}}$: The force of gravity produced by gravitating mass. | |

| ${{\mathscr{F}}}_{{\bf{af}}}$: An anisotropic force is produced by the anisotropy of the system. | |

| ${{\mathscr{F}}}_{{\bf{hf}}}$: Hydrostatic fluid generates hydrostatic force. |

| • | ${{\mathscr{F}}}_{{gf}}=\tfrac{-{\kappa }^{{\prime} }(r)({{ \mathcal P }}_{r}+\rho )}{2}$. |

| • | ${{\mathscr{F}}}_{{af}}=\tfrac{2({{ \mathcal P }}_{t}-{{ \mathcal P }}_{r})}{r}$. |

| • | ${{\mathscr{F}}}_{{hf}}=-\tfrac{{\rm{d}}{{ \mathcal P }}_{r}}{{\rm{d}}r}$. |

Figure 9. Equilibrium scenario via TOV equation with r0 = 1 and δ = 0.5 for SF-1 (left panel) and for SF-2 with r0 = 1 (right panel) |

8. Volume integral quantifier

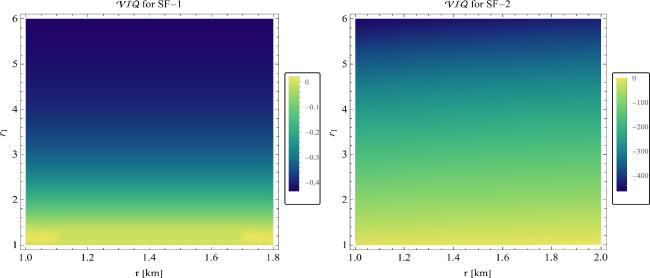

Figure 10. ${ \mathcal V }{ \mathcal I }{ \mathcal Q }$ with r0 = 1, δ = 0.5 and γ = 5 - SF-1 (left panel) and with r0 = 1, γ = 5 -SF-2 (right panel) |

9. Concluding remarks

| i | (i) The investigation is initiated by showing in figures 3 and 6 that SF-1 and SF-2 fulfill all the physical criteria for the construction of a WH. Following that, graphical representations of embedding surfaces have been shown for both the models of WHs in figures 1 and 2. |

| ii | (ii) We proceeded to the investigation by analyzing the energy conditions viz. NEC, DEC, and SEC respectively for both the models. With respect to SF-1, taking r0 = 1, 5 ≤ γ ≤ 10 and δ = 0.5, we found in figures 4 and 5 that the radial NEC is completely violated and the tangential NEC is violated within the mentioned range of γ and r while DEC and SEC also violated. On the other hand, we analyzed the characteristics of all ECs with model parameter 5 ≤ γ ≤ 10 with respect to SF-2 and found that the energy density shows positive behavior throughout the spacetime figure 7 (top left panel). With different ranges of r, the radial NEC, and radial DEC, as well as the SEC, are violated with 5 ≤ γ ≤ 10, as can be seen in figures 7 and 8. The effective energy-momentum tensor caused the violation of the WEC and turned into a source of exotic matter to support the WH solutions. |

| iii | (iii) Keeping in mind the above results, we continued the exploration regarding the stability analysis of the two WH models. For this, the equilibrium condition of the presented WH models within ${ \mathcal F }({ \mathcal R },{{\mathscr{L}}}_{m})$ gravity is introduced by the TOV equation [63] for an anisotropic configuration. This is realized as the stability of a WH is featured by three forces such as ${{\mathscr{F}}}_{{hf}}$, ${{\mathscr{F}}}_{{af}}$ and ${{\mathscr{F}}}_{{gf}}$. In the current scenario, ${{\mathscr{F}}}_{{gf}}$ has zero effect on the WH as the redshift function is constant. Figure 9 confirms that the anisotropic force (${{\mathscr{F}}}_{{af}}$) balances the hydrostatic force (${{\mathscr{F}}}_{{hf}}$). Hence, the graphical behavior of these forces shows that the WH models w.r.t SF-1 and SF-2 are in stable equilibrium. |

| iv | (iv) The quest for minimal presence of exotic matter in a WH in the framework of ${ \mathcal F }({ \mathcal R },{{\mathscr{L}}}_{m})$ drove the present study to determine volume integral quantifier. Additionally, we looked at the ${ \mathcal V }{ \mathcal I }{ \mathcal Q }$ to investigate how much exotic material is needed at the neck to create a traversable WH. We provided the graphical scenario of ${ \mathcal V }{ \mathcal I }{ \mathcal Q }$ for both SF-1 and SF-2 in figure 10. Exotic matter is present in both the WH models as it can be seen that ${ \mathcal V }{ \mathcal I }{ \mathcal Q }$ is negative for r > r0. However, near the throat, the amount of exotic matter decreases considerably as ${ \mathcal V }{ \mathcal I }{ \mathcal Q }\to 0$ as r1 → r0. This leads to the result that just a small amount of exotic matter can sustain a WH configuration near the throat for both models. |

| v | (v) Now, we will present some relevant research works on WHs in different modified theories of gravity in connection to our present work. In a power law f(T) model [50], WH solutions considering energy density to be Gaussian violate radial NEC in some region of spacetime whereas tangential NEC is valid everywhere. Later, with the assumption of linear equation of states, a dynamical model [51] in f(T) gravity for WH follows the violation of NEC with some evolving time constraint. Another the investigation [52] of WH solutions in Finsler geometry establishes violation of radial NEC for the chosen and physically valid shape functions. Further, NEC in radial direction is not satisfied but valid in a tangential direction for specific equation of state taken into account in the framework of f(R, T) gravity [53]. A similar exploration related to NEC can be found in research works [54, 55] on WHs in f(R) gravity where physically valid shape functions are taken into consideration. Again, similar results for WH solutions are obtained in a linear model under f(Q, T) gravity [56] with Gaussian and Lorentzian distribution profiles of density. In the same work [56], a non linear model for WHs shows that radial NEC fails to satisfy only near the throat. In the background of Rastall gravity, Chaudhary et al [57] developed WH configurations by utilizing various linear equations of state and showed that exotic matter is required in accordance to violation of radial NEC. Recently, Kavya et al [58] showed the behavior of ECs in the context of ${ \mathcal F }({ \mathcal R },{{\mathscr{L}}}_{m})$ by using specific forms of energy density and shape functions to produce physically viable WH solutions. In their work, NEC was found to be violated for WH model A, whereas it is satisfied for model B. Again, Solanki et al [59] provide the WH solutions in ${ \mathcal F }({ \mathcal R },{{\mathscr{L}}}_{m})$ with different equations of states and specific forms of shape function to generate WH solutions. So, the expedition to explore WH geometries under modified theories of gravity continues in our present work. We have used a similar approach to the ones used in [52, 54, 55, 60] to develop two WH models in ${ \mathcal F }({ \mathcal R },{{\mathscr{L}}}_{m})$ gravity. For both the models, the energy density ρ is positive throughout the spacetime and NEC in the radial direction is violated. This result behaves as the key feature for a stable traversable WH in GR, as well as in alternative gravities [50–58]. However, from the perspective of $f({ \mathcal Q })$ gravity, Kiroriwal et al [60] produced WH geometries by assuming physical form of shape functions which violates NEC in a tangential direction only. In contrast to the works [50, 53–56], NEC in a tangential direction is violated only for some specified region near the throat of the WH for the WH-I model. However, tangential NEC is satisfied only near the throat of the WH for the WH-II model. In comparison to [58] and [59], we provide the stability of WHs for the WH-I and WH-II, along with the behavior of different forces acting on fluid via the dynamics of TOV equation. |