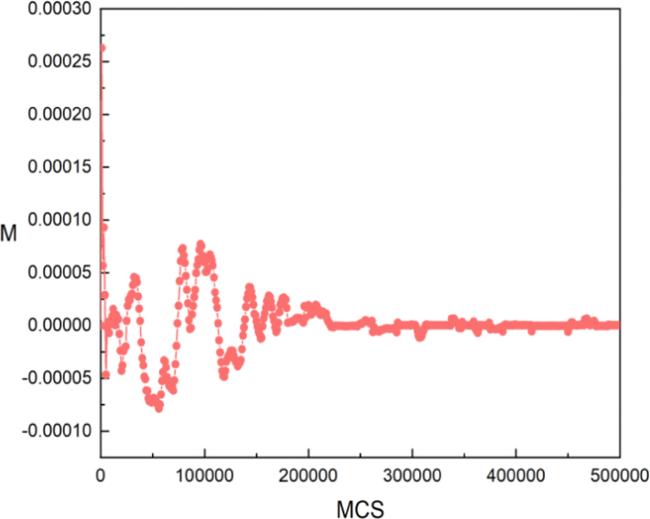

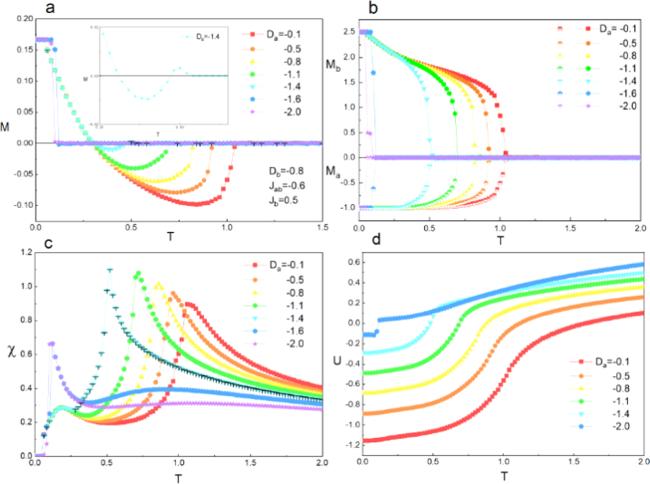

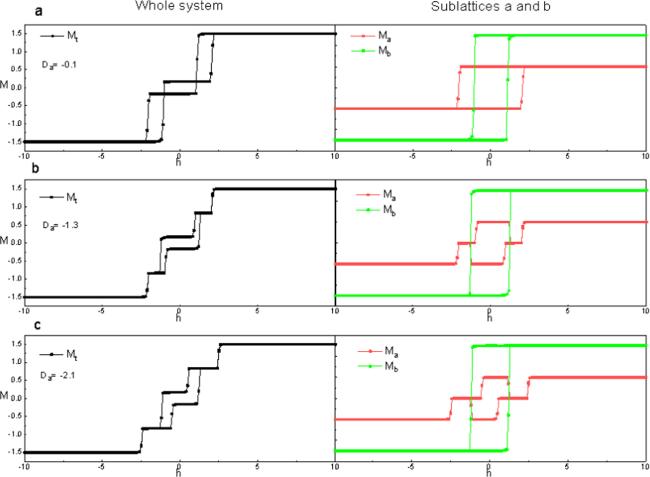

Figure

5 shows the effect of

Da on

M,

Ma,

Mb and

U when

Jab = −0.6,

Jb = 0.5 and

Db = −0.8. In figure

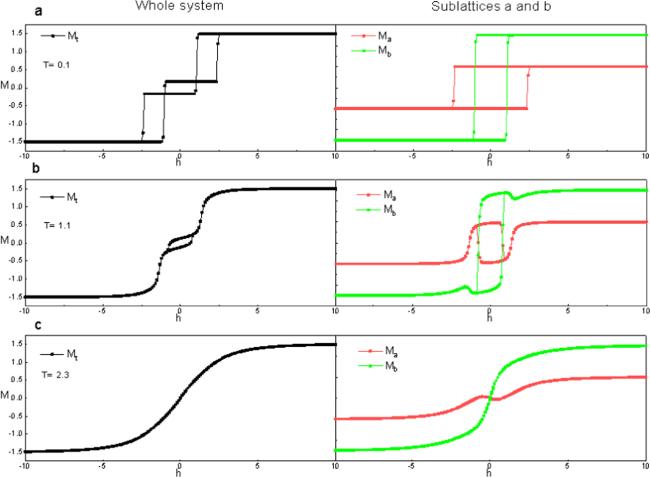

5(a), we can see that, when it is close to zero temperature, the common saturation value

M is equal to 0.167; when the value of

Da changes from −0.1 to −1.4, as

T increases,

M decays to a negative value and then gradually increases to zero, where there are two zero magnetizations, one related to the compensation temperature (

Tcomp) while the other should be the critical temperature (

TC). This

M curve has the N-type characteristic classified in ${\rm{N}}\acute{e}\mathrm{el}$ theory [

45]. Changing

Da from −0.1 to −1.1, we can see the significant N-type behavior. As $\left|{D}_{a}\right|$ continues to increase, when

Da= −2.0, −2.8, the

M curve first remains unchanged and then rapidly decreases to 0 as

T increases. This discontinuous change in the

M curve corresponds to a first-order phase transition. In addition, it should be emphasized that double compensation temperatures may exist when

Da = −1.4, as shown in figure

3(a), which is not predicted in ${\rm{N}}\acute{e}\mathrm{el}$ theory [

45]. In figure

3(b), we can notice two saturation values of

Mb= 2.5 and

Ma = −1.0 in the two curves. According to equation (

5), they are directly related to the saturation values of

M shown in figure

5(a). In figure

5(c) there is a peak at each curve, which corresponds to

TC, showing a typical second-order phase transition feature. Moreover, it gradually shifts to the right as $\left|{D}_{a}\right|$ decreases. This is consistent with the phenomenon in some magnetic particles [

46,

47]. In figure

5(d), we can see that each

U curve increases gradually as

T increases, and the place where

U changes the fastest actually corresponds to

TC.